In an era dominated by fast food, packaged snacks, and sugar-laden beverages, the Western-style diet has become the global norm in many parts of the world. While its convenience and flavor may appeal to modern appetites, the hidden consequences on the human body—particularly the gut microbiome—are becoming increasingly hard to ignore. A groundbreaking new study published in Nature by researchers at the University of Chicago paints a startling picture: the Western diet not only damages gut health but also severely impairs its ability to recover after antibiotic treatment.

A Gut Reaction: Diet and the Microbiome

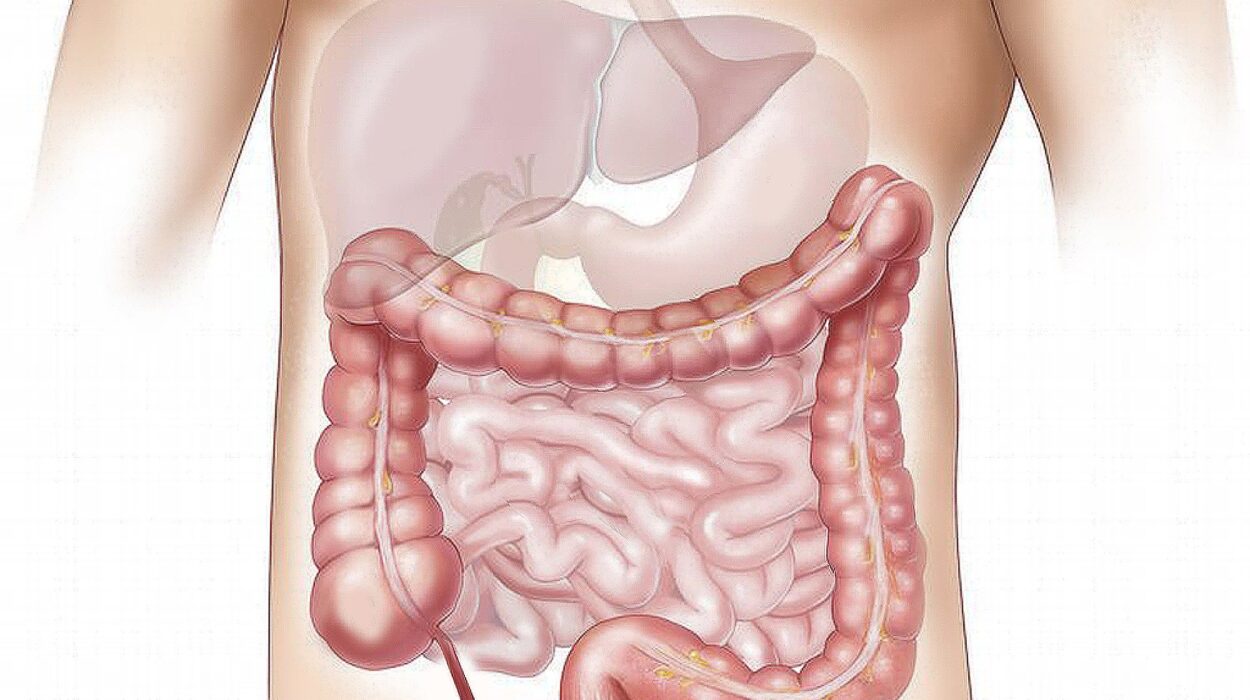

The gut microbiome is a vast and dynamic community of trillions of microorganisms—bacteria, fungi, viruses, and other microbes—that reside in the human digestive tract. These microscopic residents play critical roles in digestion, immune regulation, mental health, and even the synthesis of essential vitamins. But their wellbeing is deeply intertwined with our diet.

Modern Western diets, characterized by high intake of processed foods, red meat, dairy, refined sugars, and unhealthy fats, and low intake of fiber-rich fruits, vegetables, and whole grains, are known to diminish microbial diversity. This microbial loss reduces the variety of health-promoting metabolites produced in the gut, leaving the host vulnerable to a range of diseases, particularly those linked to immune dysfunction such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), obesity, type 2 diabetes, and even cancer.

New Findings from the University of Chicago

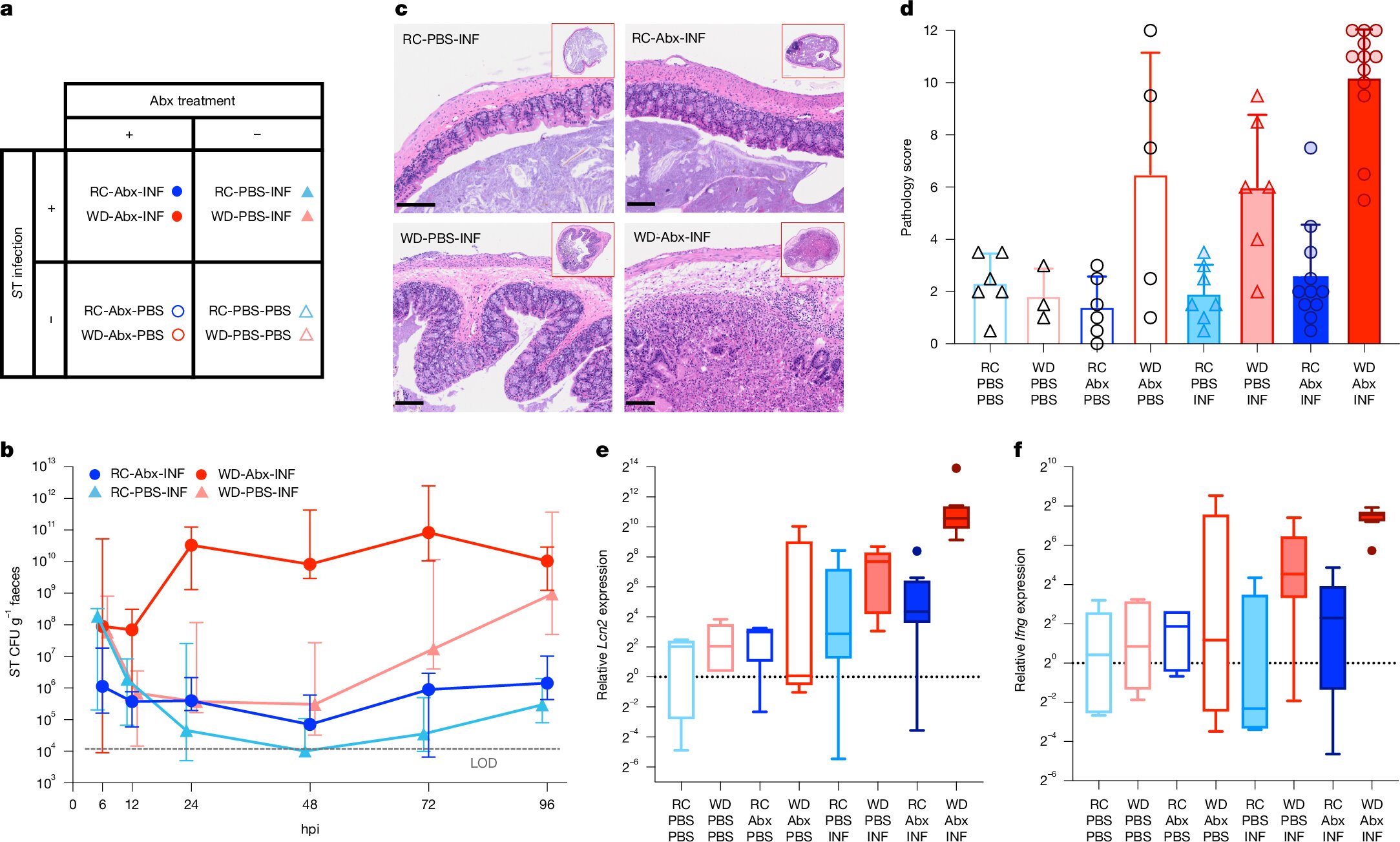

The University of Chicago research team, led by Megan Kennedy and Eugene B. Chang, set out to understand how the gut microbiome responds to antibiotics under different dietary conditions. Antibiotics, while lifesaving, are a double-edged sword—they not only kill harmful pathogens but also decimate beneficial microbial communities in the gut.

In their experiment, mice were divided into groups and fed either a Western-style diet (WD) or a regular chow (RC) that mimicked a Mediterranean-style diet—rich in plant-based fiber and low in fat. All mice were then administered antibiotics to wipe out their gut microbes, mimicking a common clinical scenario in humans.

The results were striking.

Mice on the RC diet showed a remarkable ability to recover a balanced, diverse, and healthy gut microbiome after antibiotics. In stark contrast, mice on the Western diet failed to recover, even when healthy microbes were reintroduced through a fecal microbial transplant (FMT). These mice remained vulnerable to infection from pathogens like Salmonella, a common and dangerous intestinal invader.

Rebuilding the Microbial Forest

Dr. Chang likens the gut microbiome to a forest ecosystem. When antibiotics sweep through, it’s akin to a wildfire scorching the landscape. In the aftermath, nature requires time and the right conditions to regenerate. For the gut, this regeneration depends heavily on what nutrients are available in the diet.

“When you’re on a Western diet, the regrowth process fails,” Chang explained. “That’s because it doesn’t provide the right nutrients for the beneficial microbes to flourish. Instead, a few opportunistic species dominate the environment, blocking the succession of microbial communities necessary for full recovery.”

In contrast, the fiber-rich RC diet created an optimal environment for microbial succession—a stepwise recolonization by different types of microbes that restore the ecosystem’s balance and function.

The Role of Fecal Microbial Transplant

FMT has gained attention in recent years as a treatment for conditions like recurrent Clostridioides difficile infections. The idea is to transplant beneficial bacteria from a healthy donor into the gut of a sick patient, effectively “seeding” a new microbiome. However, this study shows that FMT’s success is not guaranteed. Diet plays a critical role in determining whether the transplanted microbes can survive and establish themselves.

“It doesn’t matter how ideal your FMT is,” Kennedy noted. “If the diet doesn’t support the microbes, they simply won’t stick. The food environment dictates microbial fate.”

Implications for Human Health

The implications of this research extend far beyond mice. In humans, the overuse of antibiotics—combined with widespread consumption of the Western diet—is likely disrupting gut microbial communities on a population scale. This could help explain rising rates of chronic inflammatory diseases and increased susceptibility to infections.

Moreover, the findings have special relevance for patients undergoing cancer treatment, organ transplantation, or other interventions that involve immunosuppression and heavy antibiotic use. These individuals often face life-threatening infections from drug-resistant bacteria. While new antibiotics are being developed, this research suggests that an equally powerful tool may be sitting on our plates.

“Maybe we don’t need another antibiotic,” said Chang. “Maybe what we need is a smarter way to rebuild the gut microbiome—using food.”

A Prescription for Fiber

So what’s the solution? It may start with a simple shift in dietary habits.

Eating more plant-based, fiber-rich foods—fruits, vegetables, legumes, and whole grains—could lay the groundwork for a more diverse, stable, and resilient gut microbiome. These foods provide the necessary nutrients (like complex carbohydrates and polyphenols) that beneficial microbes use to thrive and produce anti-inflammatory metabolites such as short-chain fatty acids.

Even if going full vegan or Mediterranean isn’t realistic for everyone, small changes can still have profound effects. As Kennedy suggests, people preparing for surgery or expected antibiotic treatment might benefit from increasing their intake of gut-friendly foods in advance.

Supplements: The Middle Ground

Understanding that not everyone is ready to overhaul their diet, Chang is also exploring a hybrid strategy: developing targeted supplements designed to nourish specific microbial populations. These could help people maintain gut health even when sticking to their current eating patterns.

“This could be a ‘have your cake and eat it too’ scenario,” Chang said. “We could design supplements that mimic the effects of a high-fiber diet on the microbiome, providing the right food for beneficial bacteria even if your lifestyle doesn’t allow for perfect eating.”

Food as Medicine

The broader takeaway from this research reinforces an ancient concept now supported by modern science: food is medicine. What we eat doesn’t just fill our stomachs—it shapes the microscopic communities that protect, nourish, and regulate our bodies in countless unseen ways.

“I’ve become a believer that food can be medicinal,” said Chang. “In fact, I think that food can be prescriptive. We can eventually design diets or supplements that restore microbial health after antibiotics or illness, much like we prescribe drugs today.”

The Takeaway: Rebooting the Gut Starts with Your Plate

In the wake of this study, the message is loud and clear: diet doesn’t just affect your waistline—it determines the health of your internal microbial ecosystem and your body’s ability to recover from disruptions. Western-style eating patterns may be convenient, but they exact a hidden toll on long-term health by sabotaging your gut’s recovery processes.

So the next time you reach for that sugary snack or processed meal, consider your gut’s response. Every bite you take is a signal—to grow or to wither—for the microscopic allies within you. With a few mindful choices, we can rebuild not just our health, but the ecosystems inside us.

Eat your fruits and vegetables. Your gut will thank you.

Reference: M. S. Kennedy et al, Diet outperforms microbial transplant to drive microbiome recovery in mice, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-08937-9