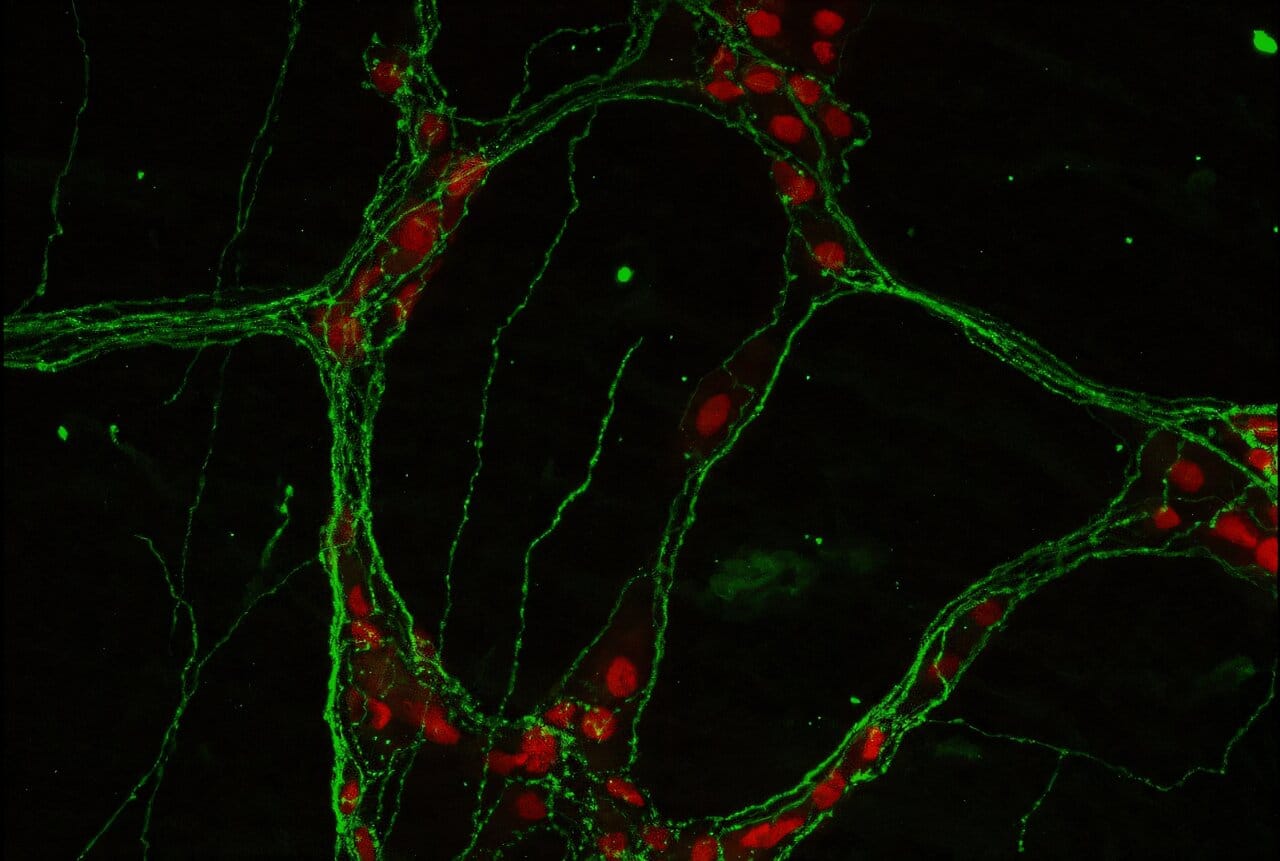

Most of us think of the brain as the organ in our skull, the seat of thought and memory. But tucked inside the walls of the intestines lies another vast network of nerve cells — the enteric nervous system. With hundreds of millions of neurons, it rivals the spinal cord in complexity and is sometimes called the body’s “second brain.”

This hidden neural web keeps food moving, regulates blood flow, and manages nutrient absorption. But according to a new study from Weill Cornell Medicine, its influence may reach even further: it helps shape how the gut heals after inflammation.

The findings, published August 15 in Nature Immunology, open up a new frontier in understanding how the gut’s neurons and immune cells communicate — and suggest fresh approaches to treating chronic disorders like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Beyond Digestion: Nerves as Immune Allies

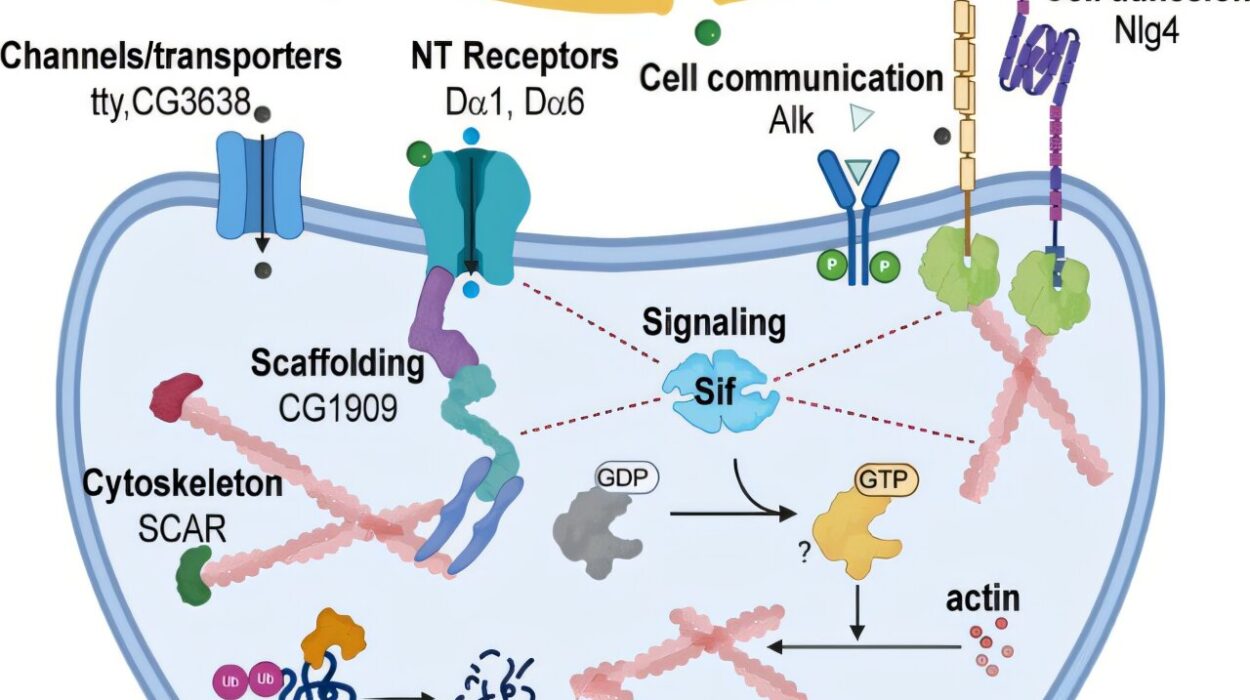

For decades, the enteric nervous system was viewed mainly as a manager of digestion, a quiet background player. But Dr. Jazib Uddin and colleagues at Weill Cornell have shown that its role is more dynamic. In their new study, they discovered that neurons in the gut produce a signaling molecule called adrenomedullin 2 (ADM2), which powerfully shapes the activity of the immune system during intestinal inflammation.

Specifically, ADM2 influences group 2 innate lymphoid cells (ILC2s), a type of immune cell nestled in the gut lining. These cells act as local guardians, secreting molecules that protect and repair tissue. When ADM2 is present, ILC2s flourish, producing amphiregulin, a growth factor that helps damaged intestinal tissue heal.

When ADM2 signaling is blocked, however, the picture changes dramatically. In a preclinical model of IBD, the absence of ADM2 left ILC2s weakened, disease worsened, and healing stalled. Conversely, administering ADM2 boosted ILC2 activity and improved gut repair.

“The enteric nervous system has long been neglected when thinking of how we can resolve detrimental intestinal inflammation,” said Dr. Uddin. “Our work suggests there may be a previously unknown neuro-immune mechanism driving intestinal healing responses.”

Translating Findings From Mice to Humans

Animal studies are essential, but the real test comes when researchers examine human biology. To bridge this gap, the team turned to samples from the Jill Roberts Institute for Research in Inflammatory Bowel Disease Live Cell Bank at Weill Cornell Medicine.

The human data mirrored the mouse experiments. Patients with IBD — including conditions such as Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis — had higher levels of ADM2 expression than healthy individuals. Even more striking, when human ILC2s were exposed to ADM2 in the lab, they ramped up production of amphiregulin, just as the mouse cells had done.

This cross-species consistency suggests that the ADM2-ILC2 pathway is not a laboratory curiosity but a fundamental biological mechanism, one that may be harnessed for therapies.

A New Way to Think About Gut Disease

The implications of this work are profound. IBD affects millions worldwide, causing chronic pain, diarrhea, fatigue, and malnutrition. Current treatments often rely on suppressing the immune system, which can bring relief but also carries risks of infection and other side effects.

The Weill Cornell findings suggest a more targeted and naturalistic approach: stimulating the gut’s own healing machinery by activating neuro-immune communication. Instead of broadly shutting down inflammation, therapies could encourage the protective conversation between neurons and immune cells.

“The findings of this current study allow new insights into how the immune and nervous systems ‘speak’ to each other and coordinate complex processes, including tissue inflammation and repair, and offer the potential for new therapies targeting these neuro-immune interactions,” said Dr. David Artis, senior author of the study and director of the Jill Roberts Institute.

Rethinking the “Second Brain”

The study also reshapes our philosophical view of the body. The gut’s nervous system is not just a passive servant of digestion. It is an active communicator, capable of influencing the immune system in ways that matter for health and disease.

This discovery adds to a growing appreciation of the gut-brain-immune axis, a complex three-way dialogue that touches everything from inflammatory disorders to mood and mental health. While much remains to be explored, ADM2 now stands as a key molecule in this intricate conversation.

Looking Ahead

As with any major scientific finding, questions remain. How exactly do gut neurons decide when to release ADM2? Could drugs be designed to mimic or enhance its effects? And are there risks to boosting this pathway in patients?

For now, what is clear is that the enteric nervous system deserves a new level of respect — not only as a regulator of digestion but as a partner in healing.

“We are only beginning to scratch the surface of how nerves and immune cells work together,” Dr. Uddin noted. “But what we are seeing is that the gut is far more intelligent than we ever imagined.”

And in that hidden intelligence may lie the future of treating some of the most stubborn diseases of our time.

More information: Uddin, J., Yano, H., Parkhurst, C.N. et al. CGRP-related neuropeptide adrenomedullin 2 promotes tissue-protective ILC2 responses and limits intestinal inflammation. Nature Immunology (2025). doi.org/10.1038/s41590-025-02243-2