From bustling cities alive at dawn to quiet dorm rooms still glowing with laptop light at 3 a.m., human beings are creatures of contrasting rhythms. Some leap out of bed with the sunrise, energized and ready to seize the day. Others thrive under moonlight, when the world slows down and creativity flows. This divergence in daily patterns isn’t just a matter of preference—it’s rooted in a phenomenon known as chronotype, a biological rhythm that shapes when we naturally feel alert or drowsy.

In a world increasingly influenced by artificial light, screens, and round-the-clock demands, understanding chronotype has never been more urgent. Recent groundbreaking research conducted by a team of neuroscientists at McGill University and the Mila–Quebec Artificial Intelligence Institute, published in Nature Human Behavior, has begun to unravel the neurobiological architecture of chronotypes. Their findings not only illuminate how our brains are wired for morningness or eveningness but also hint at the profound implications these internal clocks may have for mental and physical health.

The Biological Beat of Human Life

Chronotype is essentially your internal clock’s signature. It determines whether your brain prefers to buzz in the early morning or late at night. While it’s strongly influenced by the circadian rhythm—a roughly 24-hour cycle regulated by genes, light exposure, and hormonal changes—chronotype also emerges from a deeper biological terrain. It’s not simply about behavior; it’s about how your brain is built.

Most people fall somewhere along a spectrum. On one end are “morning larks,” who feel most alert in the morning and tend to fade by evening. On the other end are “night owls,” who hit their stride after sunset, often staying productive or creative long past midnight. In between lies a broad middle range. These preferences are more than lifestyle choices; they’re biological inclinations, often stubbornly resistant to change.

For decades, scientists suspected there might be physical differences in the brains of early risers and night owls. But clear evidence was elusive—until now.

Modern Lifestyles and the Disruption of Biological Time

The last two decades have introduced profound changes to how humans interact with time. With the advent of smartphones, video streaming, and remote work, people have gained unprecedented freedom to shape their own schedules. Yet this freedom has come at a cost.

Many have drifted into later sleep-wake cycles, tempted by endless scrolling, late-night messaging, or binge-watching into the early hours. As social and technological trends nudge bedtime later and later, science has been raising alarms. Numerous studies have shown that night owls are more likely to suffer from mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety, and are more prone to poorer physical health outcomes, including obesity, cardiovascular issues, and metabolic disorders.

Why this happens has long puzzled researchers. Are night owls biologically vulnerable, or is society simply out of sync with their natural rhythms?

Cracking the Brain’s Code: A Landmark Study

In an ambitious endeavor to probe deeper, researchers Le Zhou, Karin Saltoun, and colleagues analyzed a treasure trove of data from the UK Biobank, one of the largest biomedical databases in existence. With over 27,000 participants, the study combined advanced brain imaging techniques with phenotypic data—a wide-ranging catalog of traits shaped by genes and environment.

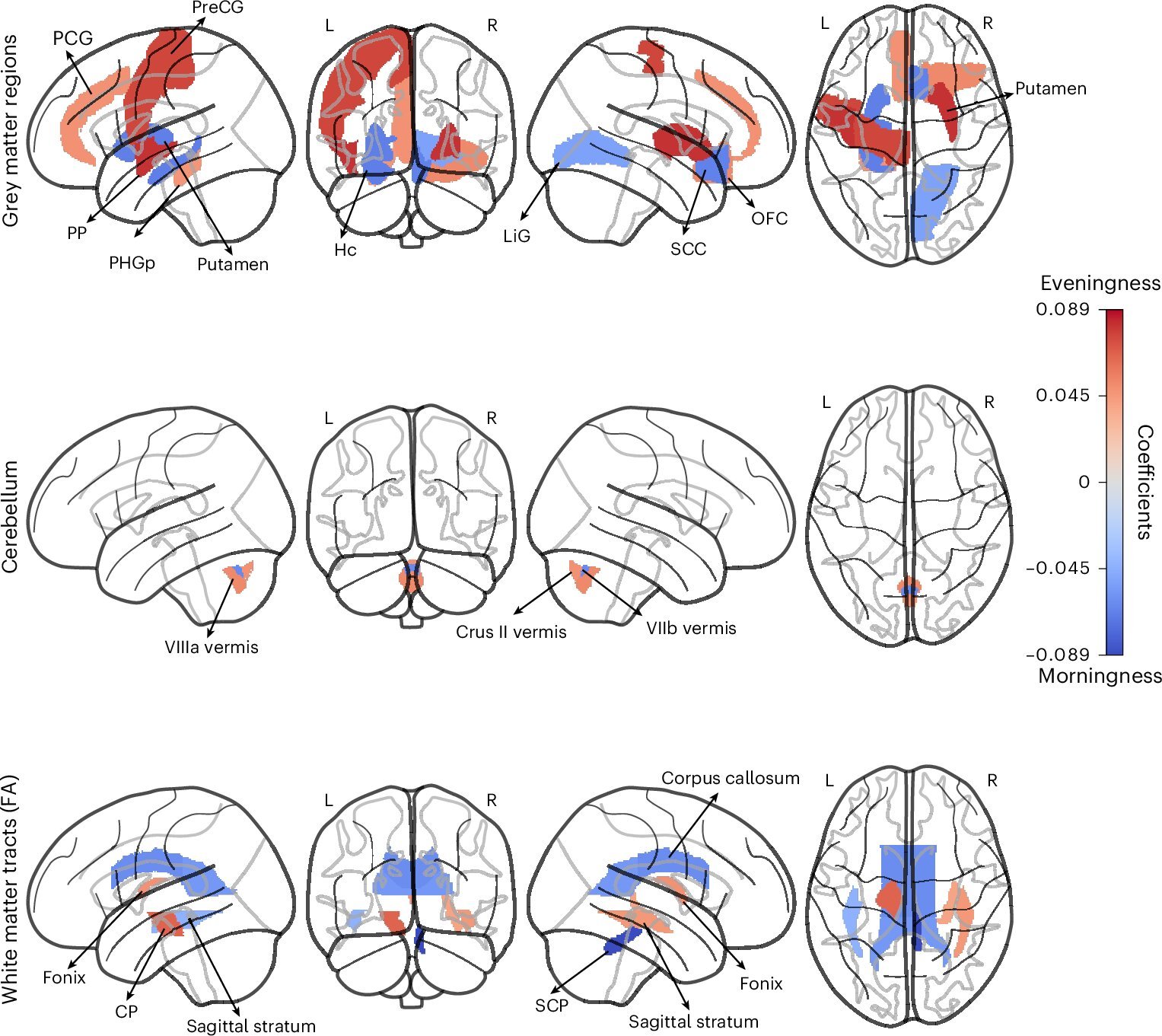

Using pattern-learning algorithms, the researchers examined three key types of brain imaging data:

- Gray matter volume (which relates to processing and cognition)

- White matter integrity (important for communication between brain regions)

- Functional connectivity (how brain regions interact in real-time)

Overlaying this neural data with nearly 1,000 phenotypes, the team uncovered a multilayered map of how chronotype is etched into the brain’s very structure.

Where Chronotype Lives in the Brain

The study revealed striking associations between chronotype and several brain regions involved in reward processing, emotional regulation, and motor control. Key players included:

- The basal ganglia, often involved in motivation, habit formation, and voluntary movement.

- The limbic system, which governs emotional responses and mood.

- The hippocampus, a crucial structure for learning and memory.

- The cerebellum, long known for its role in coordination, but increasingly recognized for its contributions to cognitive and emotional processing.

Notably, individuals with a late chronotype—those who prefer evening activity—tended to show variations in these regions that aligned with higher susceptibility to mood disorders and lower physical fitness. These patterns weren’t just visible in brain scans; they also surfaced in behavioral data collected via actigraphy—wearable devices that tracked participants’ real-world movement patterns.

Implications Beyond Sleep: Health, Emotion, and Society

This study is more than a scientific curiosity—it’s a leap toward precision mental health care. If chronotype has tangible effects on how brain circuits function and how people experience reward and regulate emotion, then it follows that interventions tailored to an individual’s chronotype could revolutionize mental health treatment.

For instance, a night owl with depression might benefit from a therapy schedule that aligns with their peak cognitive hours. Likewise, medications could be timed to coincide with biological highs and lows, optimizing efficacy while minimizing side effects.

Moreover, this work shines a light on social inequities embedded in time. Modern society is largely designed for early risers—9-to-5 workdays, school start times, morning meetings. Night owls often face a misalignment between internal and external clocks, a condition scientists call “social jetlag.” This chronic discrepancy can erode sleep quality, undermine mental health, and reinforce unhealthy behaviors.

Understanding the neurobiological legitimacy of chronotypes could lead to more inclusive policies—such as flexible work schedules, later school start times, or chronotype-aware medical screening protocols.

Chronotype and Personality: The Behavioral Link

Interestingly, the UK Biobank study also found links between chronotype and traits like impulsivity, risk-taking, and novelty-seeking. These behavioral dimensions may be tied to how the reward system functions in night owls versus morning people. For example, evening types may be more driven to pursue stimulating or unconventional experiences, which could be beneficial in creative fields but challenging in rigid environments.

On the flip side, morning types were more associated with conscientiousness, discipline, and emotional stability, qualities often favored in traditional academic and workplace settings. These differences don’t indicate superiority of one chronotype over another, but rather underscore the diversity of human cognitive styles—each suited to different roles, challenges, and times of day.

Genes, Light, and Lifestyle: A Delicate Interplay

Although brain structure plays a powerful role, chronotype is not destiny. Genetics set the stage, but environmental cues—especially light exposure—can shift the clock forward or back. The hormone melatonin, which signals sleepiness, is heavily influenced by how much light your eyes perceive.

Exposure to bright light in the morning can help advance the sleep cycle, making one more of a morning type over time. Conversely, late-night exposure to blue light from screens delays melatonin production, reinforcing night owl tendencies.

This interplay means that strategic light exposure, physical activity, and consistent sleep hygiene can help shift chronotype slightly, offering a potential path for those seeking better alignment with societal demands or personal health goals.

Toward a Chronotype-Informed Future

This research marks a turning point in our understanding of human diversity. It affirms that chronotype is a real, measurable phenomenon, deeply embedded in the brain’s structure and function. It’s not laziness or lack of discipline that keeps some people awake at night—it’s biology.

More importantly, the study opens the door to new forms of personalized medicine. Imagine a future where your mental health plan, fitness regimen, or workplace productivity strategy is tailored to your chronotype. Such an approach could revolutionize everything from how we treat anxiety to how we schedule our days.

Schools might shift start times for adolescents, whose natural chronotype tends to skew later during puberty. Employers could offer flexible work hours based on productivity windows. Mental health clinicians might ask not just what you’re feeling but also when you feel your best or worst.

Conclusion: Embracing the Clock Within

In the end, our chronotypes are a testament to the rich variability of human biology. They reflect a dance between brain and body, genes and environment, dawn and dusk. While society tends to idolize the early riser, science is increasingly showing that night owls have brains wired differently, not defectively.

As the McGill-Mila study eloquently demonstrated, the key to understanding mental health and human behavior may lie in recognizing the rhythms that beat quietly beneath our consciousness. Whether you’re greeting the sun with a cup of coffee or composing music at midnight, your chronotype is part of what makes you you—a unique expression of your brain’s internal symphony.

The challenge for science and society now is to honor these rhythms, not resist them. Only then can we hope to live in harmony with the clocks that tick not on our walls, but in our very brains.

Reference: Le Zhou et al, Multimodal population study reveals the neurobiological underpinnings of chronotype, Nature Human Behaviour (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41562-025-02182-w. www.nature.com/articles/s41562-025-02182-w