There is a story written deep within our DNA, etched into the curve of our skulls, whispered by the angle of our hips and the length of our fingers. It is a story of transformation, endurance, and unimaginable time. It is the story of human evolution—a story that spans over six million years and stretches from the forests of ancient Africa to the towers of modern cities.

We often look in the mirror and see only the present, only the now. But behind every face lies a history millions of years in the making. The human face is a mosaic of ancient innovations—upright walking, tool-making hands, curious minds, and the capacity for language and empathy. We are not separate from the natural world. We are its most recent experiment, an improbable result of cosmic chance and evolutionary trial.

And the journey from ape-like ancestors to modern Homo sapiens is one of the most remarkable tales ever discovered—not merely through legends or written texts, but through fossils, footprints, and fragments that science has pieced together, bone by bone, stone by stone.

The First Steps into Humanity

Six to seven million years ago, in the dense woodlands and grasslands of central Africa, something profound began to happen. The world was changing. Tectonic shifts were altering the landscape. Forests gave way to savannahs. Climate patterns became less predictable. And among the apes that roamed the trees, some began to do something strange—they started to walk.

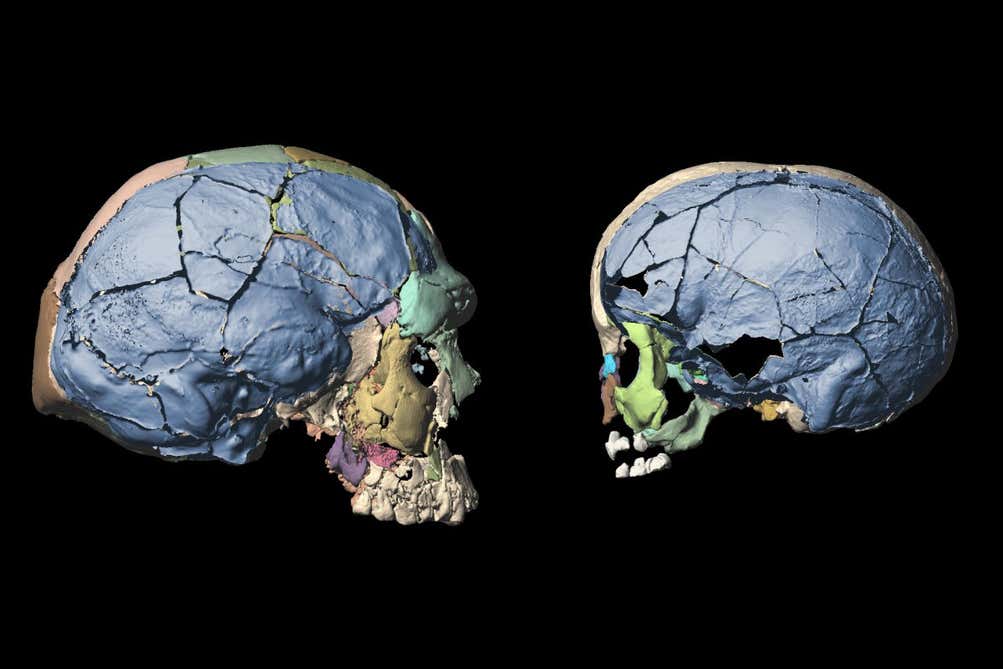

Not all at once. Not gracefully. But fossil evidence from species like Sahelanthropus tchadensis, discovered in Chad and dating to about 7 million years ago, reveals skull features suggestive of upright posture. Its foramen magnum—the hole in the skull where the spinal cord exits—was positioned in a way that suggests the head sat atop an upright spine. It may have still climbed trees, but it could also walk.

A few million years later, Orrorin tugenensis in Kenya and Ardipithecus ramidus in Ethiopia show clearer signs of bipedalism. Ardi, as she is affectionately known, lived about 4.4 million years ago and represents one of the earliest known human ancestors capable of walking on two legs while still retaining features for tree-climbing.

Walking upright was not just a quirky trick. It freed the hands. It allowed early hominins to carry objects, see over tall grass, and travel long distances under the blazing African sun more efficiently. It was the evolutionary foundation upon which all later human traits would build.

Australopithecus: The Dawn of Humanlike Beings

About 4 to 2 million years ago, a diverse group of hominins known as Australopithecus flourished across East and Southern Africa. They were fully bipedal, with small brains but increasingly humanlike bodies.

Among them was Australopithecus afarensis, famously represented by the partial skeleton nicknamed “Lucy,” discovered in Ethiopia in 1974. Lucy lived about 3.2 million years ago. She stood just over three feet tall, with a small brain around 400 cubic centimeters—less than a third of modern human size—but she walked upright with remarkable efficiency.

Lucy and her kind left behind not just bones, but footprints. In Laetoli, Tanzania, fossilized tracks preserved in volcanic ash reveal three individuals walking side by side, upright and barefoot, across the savannah more than 3.5 million years ago. It is one of the most hauntingly intimate relics of our deep past: an ancient family frozen in time, walking toward the unknown.

Though small-brained, Australopithecus used simple tools and may have had rudimentary communication. They were prey as often as they were predator, living in a precarious world where survival meant constant vigilance. Their lives were short, hard, and driven by the raw demands of nature. But evolution was at work, quietly, relentlessly.

The Rise of the Genus Homo

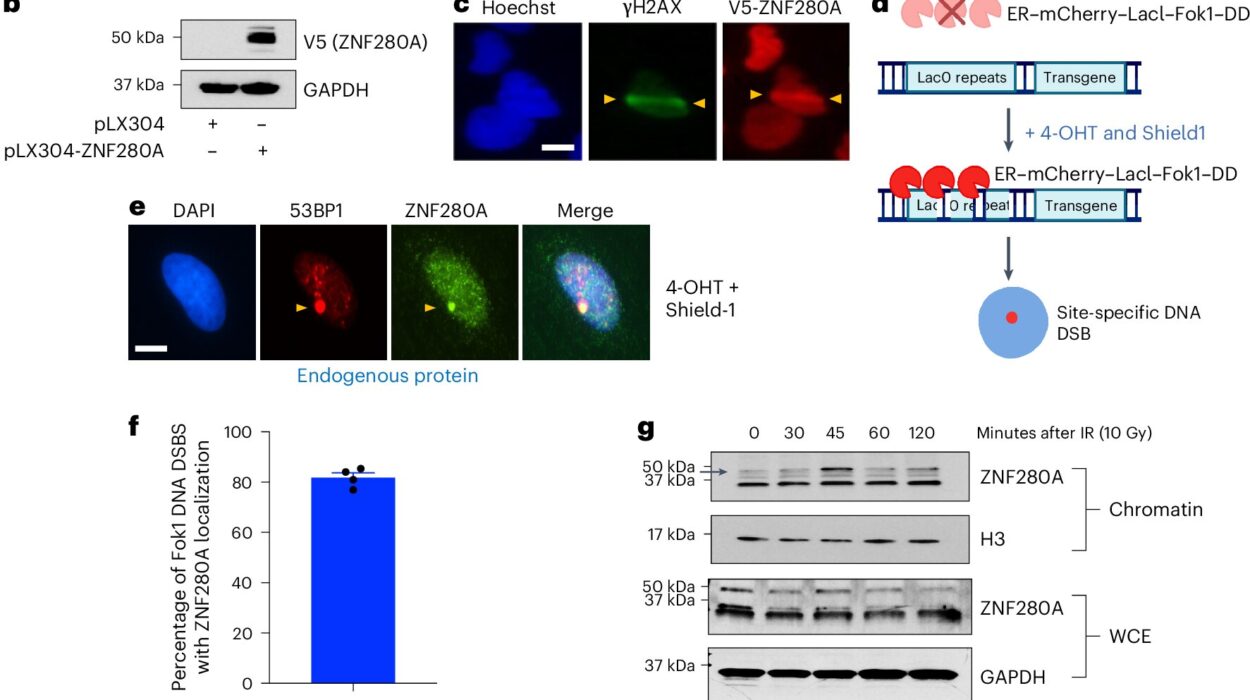

Around 2.8 million years ago, a new kind of hominin emerged—one with a slightly larger brain, smaller teeth, and a growing dependence on tools. These were the first members of our own genus: Homo.

The earliest known example, Homo habilis—“handy man”—appeared in East Africa. Though still primitive by modern standards, Homo habilis was a game-changer. They used sharp stone tools to butcher meat, crack bones for marrow, and carve their way into a broader ecological niche. Tool use was not just about survival—it was about thinking ahead, planning, shaping the environment.

With tool use came greater cooperation. Meat-sharing likely required social structures and perhaps even the earliest forms of language. Brain size continued to increase. Over hundreds of thousands of years, selection pressures favored those who could solve problems, remember locations, anticipate danger, and communicate effectively.

By 1.8 million years ago, Homo erectus had emerged—the first true global explorer. H. erectus had a modern human-like body, with long legs for running and walking, and a brain approaching 1,000 cubic centimeters. They harnessed fire, crafted more sophisticated tools, and migrated out of Africa into Asia and Europe. Their fossils have been found from Indonesia to Georgia, suggesting they were adaptable, innovative, and tough.

Some populations of H. erectus survived for more than a million years—an astonishing run for a hominin. They laid the foundation for later species, including ourselves.

Branches of the Human Family Tree

Human evolution was never a straight line. It was a branching tree, full of experiments, dead ends, and astonishing variety. Over the last two million years, multiple hominin species lived at the same time, overlapping and sometimes interbreeding.

In Europe, Homo heidelbergensis evolved from H. erectus, becoming taller, more robust, and brainier. They were likely the ancestors of the Neanderthals—Homo neanderthalensis—who would dominate the cold climates of Europe and western Asia.

Neanderthals were no brutish cave dwellers. They were highly intelligent, socially complex, and emotionally aware. They buried their dead, crafted sophisticated tools, and may have had language. They even wore ornaments and created cave art.

Meanwhile, in Africa, a separate lineage led to anatomically modern humans—Homo sapiens—who appeared around 300,000 years ago. These early humans evolved in a cradle of rich ecological complexity, facing rapidly changing climates and diverse environments. Natural selection favored flexibility, innovation, and social cohesion.

Other branches of the tree included Homo floresiensis—the “hobbit” species found on the Indonesian island of Flores—and Homo luzonensis in the Philippines. In Siberia, a mysterious group known as the Denisovans left traces of DNA but little fossil evidence. These groups are not footnotes—they are chapters in a vast, interconnected saga.

The Birth of Modern Humans

Around 200,000 to 300,000 years ago, in Africa, the first fully modern humans emerged. They looked like us, thought like us, and felt like us. But they were not yet alone. For tens of thousands of years, Homo sapiens shared the world with Neanderthals, Denisovans, and others.

What gave H. sapiens the edge? There was no single factor, but a combination of biology and culture. We developed complex language, symbolic thought, and cumulative learning. We painted on cave walls, buried our dead with care, and created myths. Culture became a force of evolution itself, allowing knowledge to build across generations.

Between 60,000 and 100,000 years ago, small bands of modern humans began to leave Africa. They migrated into the Middle East, Asia, Australia, and eventually Europe. Along the way, they encountered—and sometimes interbred with—other hominin species. Most humans today carry small percentages of Neanderthal and Denisovan DNA, especially in Europe and Asia.

But by around 40,000 years ago, most of the other hominins were gone. The reasons are still debated. Competition, climate change, disease, and hybridization likely all played roles. The age of Homo sapiens had begun.

The Cognitive Revolution and the Rise of Civilization

For tens of thousands of years, modern humans lived as hunter-gatherers. They moved with the seasons, relied on deep knowledge of their environments, and formed tightly knit groups. Art flourished—cave paintings in Lascaux and Chauvet, figurines like the Venus of Willendorf, and carved tools show a rich symbolic world.

Then, around 10,000 years ago, the Neolithic Revolution transformed everything. Humans began to domesticate plants and animals. Agriculture allowed populations to grow, leading to villages, cities, and eventually civilizations.

This change was not universally positive. Farming brought surplus food but also malnutrition, social inequality, and disease. Yet it laid the foundation for written language, technology, and the modern world.

From the river valleys of Mesopotamia to the ancient cities of the Americas, humans built societies based on cooperation, hierarchy, belief, and trade. Evolution was no longer just biological—it had become cultural, accelerating in unpredictable ways.

We Are All Africans: The Unity Beneath the Surface

One of the most powerful revelations of modern genetics is that all humans alive today descend from African ancestors. The out-of-Africa model, supported by both fossil and genetic evidence, shows that our species originated in Africa and then dispersed across the globe.

Beneath superficial differences in skin color, hair texture, or facial features lies a genetic unity. The genetic variation between any two humans is incredibly small—about 0.1%—and most of it is found within populations, not between them.

Race, as commonly defined, has no biological basis. It is a social construct built on cultural and historical forces, not scientific ones. Our differences are beautiful, but they are recent. In the long view of evolution, we are a single, intertwined family.

Evolution Never Stopped

Though we often speak of evolution in the past tense, it never ended. Natural selection still acts on our species. Modern humans continue to evolve—through changes in genes related to disease resistance, high-altitude adaptation, and dietary tolerance.

But now, cultural evolution outpaces biological evolution. We’ve shaped our environments more than they shape us. We build machines, modify genes, and contemplate colonizing other planets.

And yet, the same ancient forces still shape us. We love, fear, mourn, and dream because of neural circuits forged over millions of years. Our behavior is a dance between biology and culture, instinct and reason, ancestry and imagination.

The Fragile Miracle of Being Human

The story of human evolution is not one of destiny. It is a story of contingency, chance, and resilience. There were many paths that might have been taken. Other hominins might have survived. Our species might never have emerged. And even now, our future is not guaranteed.

But understanding our past offers something deeper than facts. It offers perspective. It reminds us that we are part of nature—not separate from it. That the divisions we draw are shallow compared to the unity we share. That our ancestors, though long gone, still live in us—in our bones, our genes, our dreams.

Every step you take today carries echoes of the first hominin who stood upright. Every word you speak descends from the brain that evolved to communicate in the darkness of prehistory. Every hand that builds, comforts, or destroys carries the legacy of the first toolmakers.

We are not alone in our story. We are the latest verse in a poem that began millions of years ago. And we are the storytellers now, able to look back not just in awe, but with understanding—with science as our guide and wonder in our hearts.

This is the story of us—not just how we became human, but what it means to be human.