Long before language, poetry, philosophy, or science—before cities rose and civilizations fell—our ancestors were creatures of instinct and reaction. They navigated a harsh and unpredictable world where survival was the only imperative. Food, shelter, reproduction, and safety defined their existence. It was in this crucible of survival that the earliest sparks of brain evolution were kindled.

The story of the human brain is not one of overnight genius. It is a saga stretching across millions of years, beginning not with humans but with simpler creatures—fish with primitive neural cords, reptiles with enlarged sensory lobes, and early mammals with growing memory systems. Each generation carried forward tiny changes in brain structure, mutations that proved useful, traits that enhanced perception, attention, or response time.

These incremental changes, shaped by the environment and refined by natural selection, gave rise to the astonishingly complex organ we carry today: the human brain. It is a story of transformation that reveals how evolutionary pressures sculpted not only our anatomy but the very essence of what makes us human—our thoughts, dreams, fears, and consciousness itself.

From Reptilian Reflexes to Mammalian Emotion

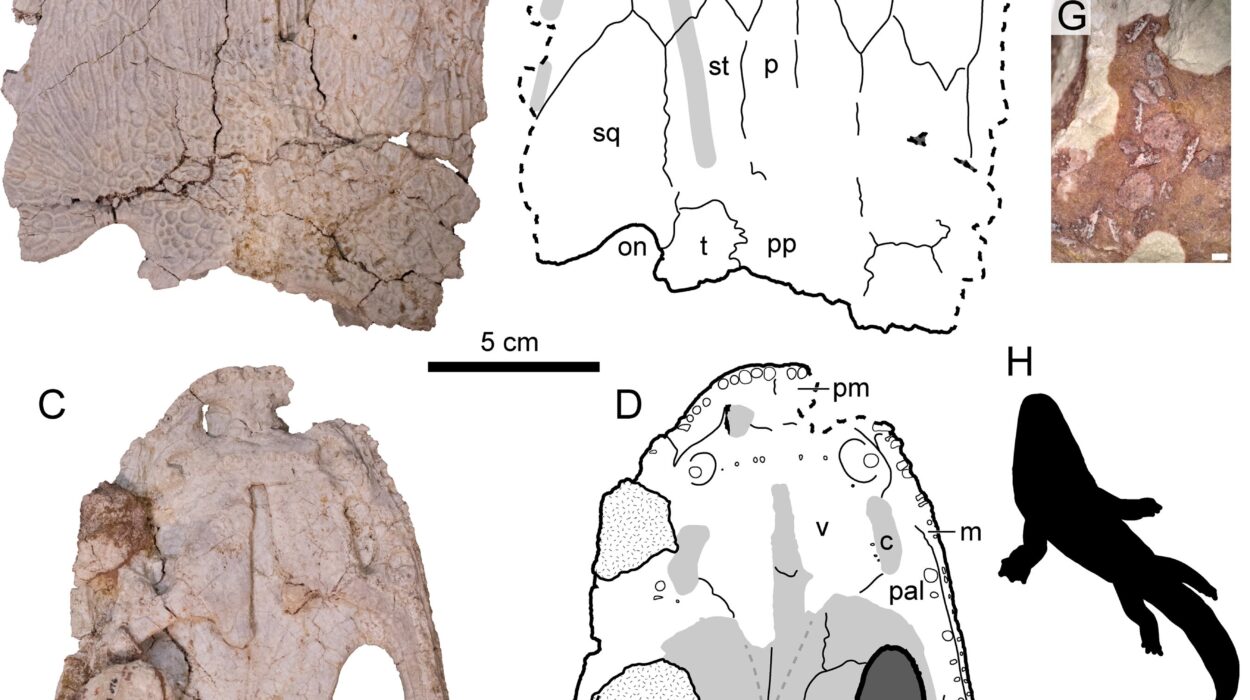

The earliest vertebrates, living some 500 million years ago, had nervous systems just sophisticated enough to sense light and motion and respond reflexively. As life moved from water to land, new challenges emerged: gravity, temperature changes, new predators, and more complex food sources. In response, brains became more specialized.

Reptiles developed brains with enlarged areas devoted to sensory processing and motor control. This so-called “reptilian brain” still exists deep within us today, centered in the brainstem and basal ganglia. It governs instincts—fight or flight, territoriality, mating, dominance. It is reactive, not reflective.

But evolution did not stop there. As small nocturnal mammals emerged during the age of dinosaurs, they needed better ways to navigate the dark, detect predators, and care for vulnerable offspring. This evolutionary pressure led to the development of the limbic system, the seat of emotion and memory.

The limbic system allowed mammals to feel in ways reptiles could not. They could experience fear, bond with their young, remember dangers, and make emotional decisions. Love, grief, loyalty—these foundational human emotions had their roots in this ancient neural upgrade. With the limbic system came not only survival, but the beginnings of social life, empathy, and trust.

The Primate Leap: Vision, Dexterity, and Social Intelligence

Around 60 million years ago, primates began to diverge from other mammals. They took to the trees, where three-dimensional navigation, hand-eye coordination, and depth perception became vital. This led to the expansion of the visual cortex and a reduction in reliance on smell. Forward-facing eyes and color vision evolved, giving early primates better ability to judge distances and identify ripe fruits and predators.

Grasping hands with opposable thumbs further enhanced their interaction with the world. They could manipulate objects, use tools, groom each other, and carry infants while moving. This physical dexterity was mirrored by increasing cognitive complexity. To live successfully in dynamic arboreal environments, early primates needed to remember food locations, recognize group members, and interpret social cues.

This period saw the enlargement of the neocortex, especially in areas devoted to sensory integration and social behavior. Brain size began to correlate with group size—a phenomenon known as the “social brain hypothesis.” Those who could manage complex relationships had a reproductive advantage. Evolution began rewarding intelligence not only for tool use or foraging, but for understanding others.

The Australopithecine Dawn: Walking Upright and Thinking Differently

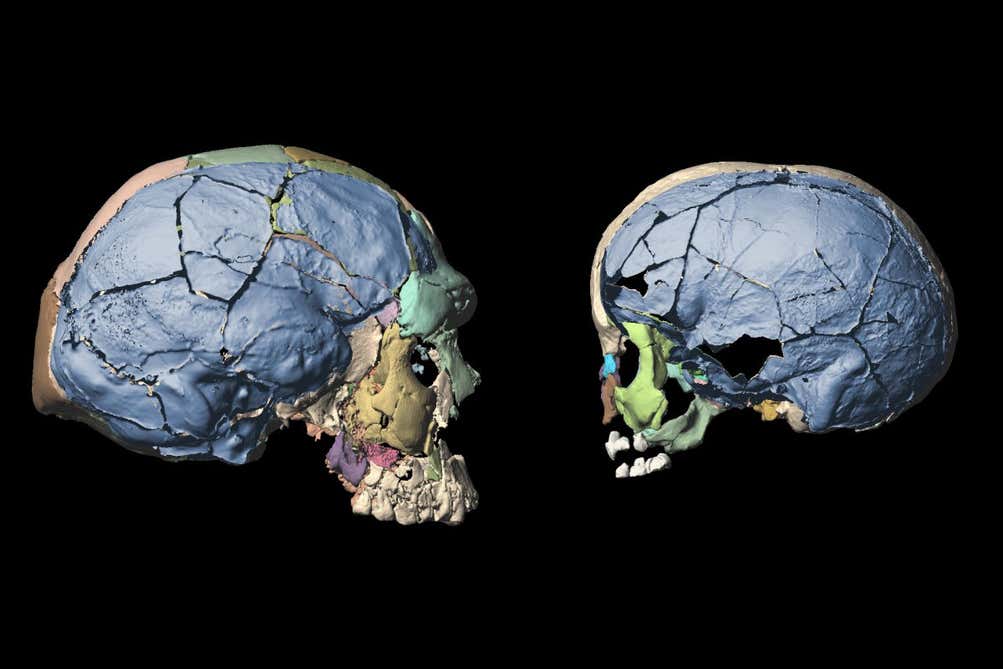

Between 4 and 2 million years ago, hominins—our direct ancestors—began walking upright. This change in posture liberated the hands and offered better visibility over tall grasses. But bipedalism also created new biomechanical challenges, including the need to balance on two feet and support the head in a different position. It required adaptations in the spine, pelvis, and skull—and eventually, in the brain.

The shift to walking upright freed the hands for complex tasks. Hominins could now carry tools, food, and infants over long distances. This behavioral flexibility encouraged greater cognitive development. Tool use itself—a major milestone—emerged around 2.6 million years ago with species like Australopithecus and later Homo habilis. Creating and using tools required foresight, planning, and fine motor control. Evolution began selecting for individuals with better spatial reasoning and memory.

With each evolutionary step, the brain grew larger, particularly in the prefrontal cortex, responsible for planning, problem-solving, and decision-making. This was no longer just about reacting to threats or finding food. It was about thinking ahead—imagining what could happen and altering behavior accordingly. The human brain was beginning to not only respond to the world, but to shape it.

Fire, Cooking, and the Feeding of the Mind

Around 1.5 million years ago, a monumental discovery changed everything: the control of fire. While wildfires had always existed, early humans learned to harness fire intentionally, perhaps first for warmth and protection, then for cooking. This innovation had a profound effect on brain evolution.

Cooking food breaks down complex molecules, making nutrients more accessible and reducing the energy required for digestion. This allowed our ancestors to consume more calories and spend less time chewing and foraging. According to the expensive tissue hypothesis, the energy saved from shrinking gut size could be redirected toward brain growth.

Indeed, during this period, brain size increased dramatically. Homo erectus had a brain nearly twice the size of its australopithecine ancestors. Larger brains supported more complex social structures, better hunting strategies, and improved communication. The cycle fed itself: smarter individuals could extract more from the environment, increasing their chances of survival and reproduction.

Cooking was not merely a practical breakthrough. It was a cultural one. Shared meals around a fire encouraged cooperation, storytelling, and teaching. Firelight became the cradle of community—and the human brain grew into a social, cultural, and imaginative organ.

Language and the Birth of Inner Thought

One of the most profound transformations in the history of the human brain was the development of language. Though no one knows precisely when language emerged, most evidence suggests it became fully developed between 50,000 and 100,000 years ago.

Language was not just a new way to communicate; it was a new way to think. It required the coordination of multiple brain regions: Broca’s area for speech production, Wernicke’s area for comprehension, the auditory cortex for processing sound, and complex motor regions for controlling the tongue and mouth.

But language also rewired the brain for abstraction. It allowed humans to share knowledge across generations, imagine events that hadn’t happened, construct social rules, create myths, and express love or rage with precision. Words gave structure to emotions and clarity to chaos.

With language came a new kind of memory—not just episodic memory of personal experiences, but semantic memory, the storage of facts, concepts, and relationships. Storytelling wove individual memories into collective knowledge. Songs, symbols, and rituals carried information across centuries. The brain had become a time machine.

The Cultural Explosion and Cognitive Modernity

About 50,000 years ago, something extraordinary happened: humans experienced a burst of creativity and innovation unlike anything before. Archaeologists call it the Upper Paleolithic Revolution or the Great Leap Forward. In a relatively short period, humans began producing cave art, wearing jewelry, burying their dead with care, and crafting sophisticated tools.

What caused this sudden explosion in behavior? Many scientists believe it wasn’t a change in brain size—by then, the brain had already reached its modern volume—but a change in brain wiring and cognitive capacity. The key may have been increased neural connectivity, particularly in the prefrontal cortex.

This region, often called the “CEO of the brain,” governs self-awareness, moral judgment, and long-term planning. Its maturation during adolescence allows for impulse control, empathy, and imagination. As this region became more finely tuned, humans could simulate scenarios in their minds, delay gratification, and form complex societies.

Culture and cognition began evolving together. Art, music, religion, and politics were not luxuries—they were expressions of a new kind of mind, capable of creating shared realities. Evolution had given rise not just to intelligence, but to wisdom, imagination, and identity.

Agricultural Settlements and the Social Brain

Roughly 10,000 years ago, humans transitioned from nomadic hunting and gathering to settled agricultural life. This transformation brought profound changes in diet, health, social structure—and brain function.

Permanent settlements required new forms of cooperation and division of labor. People needed to coordinate planting cycles, manage surplus food, and resolve disputes. Hierarchies and laws emerged, as did written language and record-keeping.

This complex social environment placed new demands on the brain. The medial prefrontal cortex, involved in understanding others’ beliefs and intentions, became more critical than ever. Living in large groups required sophisticated social cognition. Those who could negotiate alliances, detect deception, and maintain reputations were more likely to succeed.

Yet this new lifestyle also introduced problems. Crowded living conditions spread disease. Hierarchies created inequality. Diets rich in carbohydrates but poor in nutrients affected health and possibly brain development. Still, the brain adapted. It became ever more flexible, capable of navigating both the natural world and the artificial ones we created.

The Modern Brain in a Technological World

Fast forward to today. The average human brain is about 1,350 cubic centimeters—roughly the size it’s been for the past 200,000 years. But how we use our brains has changed dramatically. Modern life presents a cognitive landscape our ancestors could never have imagined.

We live surrounded by symbols, screens, and systems. We navigate social media networks, operate machinery, drive cars, learn calculus, compose music, and simulate virtual worlds. Our environments are no longer shaped just by nature but by culture, economy, and technology.

Some scientists wonder whether the human brain is still evolving—or if it has reached a plateau. Genetic studies suggest that evolution never stops. New pressures continue to act on us: stress, pollution, digital stimulation, longer lifespans, and changing reproductive patterns. Some genes related to brain size and cognition show signs of recent selection.

Others worry that modernity overwhelms our evolutionary heritage. Our brains evolved for cooperation, movement, and face-to-face interaction—not for scrolling endlessly through curated feeds or living under constant information bombardment. Mental health struggles, attention disorders, and anxiety may partly reflect a mismatch between ancient wiring and modern life.

Yet the brain remains resilient. Neuroplasticity—the brain’s ability to rewire itself—means we can adapt to new technologies, learn new skills, and recover from trauma. The brain that once carved flint tools can now program satellites. It remains the most dynamic, mysterious, and astonishing product of evolution.

Consciousness and the Edge of Understanding

At the heart of our evolutionary journey lies the deepest mystery: consciousness. How did billions of neurons give rise to awareness? Why do we feel, dream, love, and suffer? How does matter become mind?

Science has yet to fully answer these questions. Some researchers believe consciousness emerged gradually as brain complexity increased. Others argue it’s a fundamental property of certain neural circuits. What’s clear is that consciousness confers evolutionary advantages. It allows us to simulate possibilities, make moral choices, and reflect on our own existence.

But it also brings existential anxiety. We are the only species, as far as we know, that can imagine its own death. The same brain that solved the laws of physics can suffer depression. The mind that mapped the stars can feel lost in the dark.

Perhaps that is the price of such extraordinary cognition. Evolution gave us brains not just to survive, but to ask why. And in that questioning lies our humanity.

A Living Legacy

The story of how evolution shaped the human brain is not just a scientific tale—it is a story about us. Every thought you think, every memory you recall, every song you sing or story you tell is a continuation of this ancient process. Your laughter, your fears, your dreams—they are echoes of an evolutionary journey written in neurons and synapses.

We are not just products of evolution. We are its storytellers. We can reflect on where we came from and imagine where we’re going. We can sculpt our minds, change our societies, and care for one another in ways no other species ever could.

And perhaps that is the most human thing of all—not intelligence, but empathy. Not power, but understanding. Not just surviving, but seeking meaning in the cosmos.

The brain you carry today is the most complex structure in the known universe. It took hundreds of millions of years to take shape. Treat it with awe. Use it wisely. And never stop evolving.