Few questions stir as much curiosity, confusion, and controversy as this: Did humans evolve from monkeys? It’s the kind of question that children ask innocently, the kind that sparks fierce debates in classrooms and social media comment sections. It’s a question often tossed like a gauntlet into the arena of science versus belief, modern knowledge versus traditional understanding. But behind the simplicity of those six words lies one of the most profound scientific stories ever told—the story of where we came from.

The answer is not a simple yes or no. To say “yes” would be to misrepresent the science. To say “no” would be to dismiss the deep biological connections we share with other primates. The truth, like evolution itself, is more nuanced, more astonishing, and more deeply rooted in the fabric of life than many imagine.

This is the story of human origins—told not in myths or metaphors, but in fossils, DNA, ancient bones, and the echoes of our primate cousins.

Understanding What Evolution Really Means

Before we can tackle the monkey question, we have to first understand what evolution actually is. Evolution is not just a theory—it’s a scientific fact supported by mountains of evidence across biology, paleontology, genetics, embryology, and even geology. But it’s often misunderstood.

Evolution is the process by which species change over time through genetic variation and natural selection. It does not mean that a monkey suddenly turned into a human. Instead, it means that all living things share common ancestors, and over millions of years, small genetic changes accumulate, eventually leading to the formation of new species.

In the case of humans, our story is deeply tied to that of other primates, especially the great apes—chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans. These creatures are not our ancestors, but our relatives. We didn’t evolve from them; rather, we share a common ancestor with them. That common ancestor lived millions of years ago, and from it sprang multiple branches—some leading to modern chimpanzees, others to gorillas, and one extraordinary branch leading to us: Homo sapiens.

From Forest Shadows to Open Plains

The evolutionary journey of humans begins in the ancient forests of Africa more than 6 million years ago. The climate was shifting. Dense jungles gave way to patches of open savanna. Life was changing, and species were forced to adapt.

Among the primates navigating this transforming world were creatures that bore little resemblance to modern humans. They walked on all fours, lived in trees, and had small brains. But something remarkable was about to unfold.

Some of these creatures began to experiment with a new way of moving—walking upright on two legs. This simple change, known as bipedalism, would set the stage for everything that came after. Walking on two legs freed the hands. And with free hands came the possibility of carrying food, using tools, and eventually crafting the first human technologies.

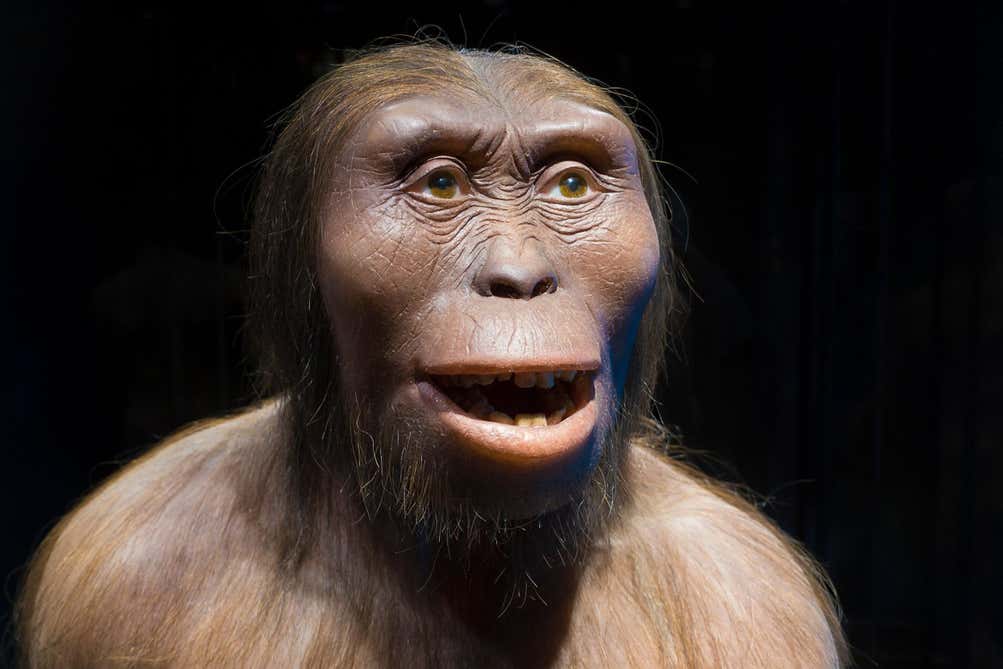

The fossil record gives us snapshots of these early experiments. Species like Sahelanthropus tchadensis (around 7 million years ago) and Australopithecus afarensis (around 3.6 million years ago) walked the Earth long before modern humans. One of the most famous fossils ever found, a 3.2-million-year-old skeleton named “Lucy,” belonged to Australopithecus afarensis. She had a small brain, long arms, and curved fingers—ideal for climbing—but her pelvis and legs showed that she walked upright.

Lucy was not a monkey. She was not a chimpanzee. She was something in between—an ancient cousin in the human family, more advanced than apes, not yet human.

What the Bones Tell Us

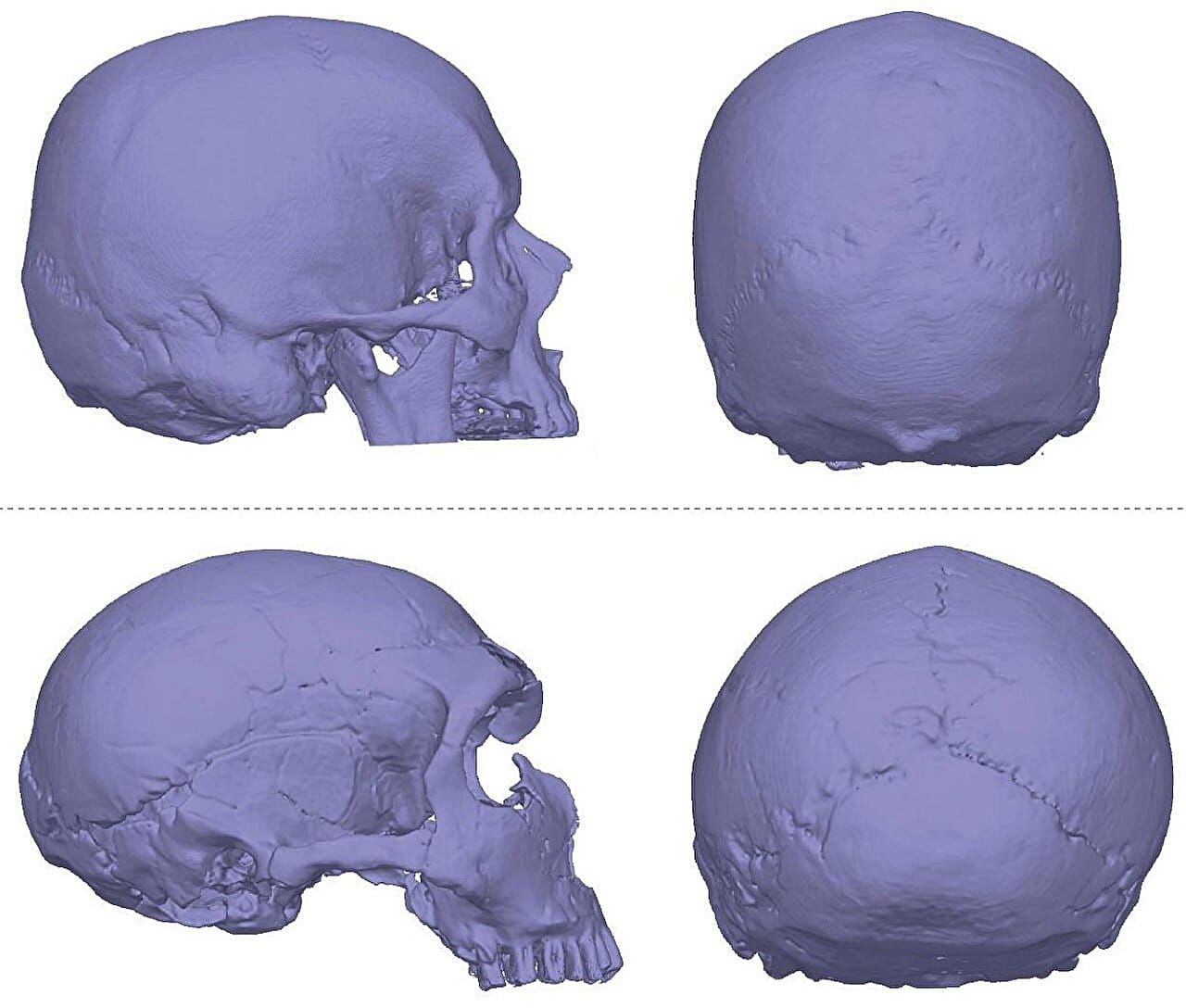

The story of human evolution is written in stone—literally. Fossils of early hominins (members of the human lineage) have been uncovered across Africa, each discovery adding another piece to the puzzle. These fossils show a gradual increase in brain size, a shift in facial structure, and the development of tools and culture.

Around 2.5 million years ago, a new type of hominin emerged—Homo habilis, often called the “handy man” because of his association with the earliest known stone tools. This marked the dawn of the genus Homo, the group to which all modern humans belong.

Next came Homo erectus, the first hominin to leave Africa, spreading into Asia and Europe. Homo erectus walked fully upright, made more complex tools, and may have used fire. Some fossils show evidence of cooperative hunting and care for injured individuals. These were not mere apes. These were intelligent, adaptive beings—creatures who were beginning to look, think, and behave in ways that foreshadowed modern humanity.

Still, they were not us.

Our Closest Living Relatives

So what about the monkeys?

In everyday language, “monkey” is used loosely to describe a wide range of primates. Scientifically, monkeys belong to a group separate from apes. Monkeys tend to have tails, smaller brains, and more primitive behaviors. Humans did not evolve from monkeys, but both monkeys and humans share common ancestry with earlier primates.

Our closest living relatives are not monkeys but great apes, especially chimpanzees. Genetic studies have revealed that humans share about 98.8% of their DNA with chimpanzees. That’s a staggering level of similarity, and it reflects our shared evolutionary history.

Imagine a family tree, where modern humans and chimpanzees are on two separate branches, but those branches connect lower down at a common ancestor. That ancestor lived about 6 to 7 million years ago. It wasn’t a chimpanzee or a human—it was a different kind of primate from which both lineages evolved in different directions.

Some of its descendants became chimpanzees. Others, over millions of years and through many transitional species, became us.

The Rise of Homo sapiens

The final act in the human evolutionary drama began around 300,000 years ago with the emergence of Homo sapiens—our own species. By this time, humans had large brains, complex languages, advanced tools, and rich social lives.

But we were not alone.

Other hominin species coexisted with us, including the Neanderthals (Homo neanderthalensis) in Europe and the Denisovans in Asia. These were not primitive cavemen, as once believed. They made art, buried their dead, and even interbred with early modern humans. Today, many people carry small percentages of Neanderthal or Denisovan DNA—living echoes of ancient encounters.

Over tens of thousands of years, Homo sapiens spread across the globe, adapting to every environment—from icy tundras to tropical rainforests. We crossed oceans, built civilizations, and eventually harnessed the power of science itself to understand our past.

What DNA Reveals

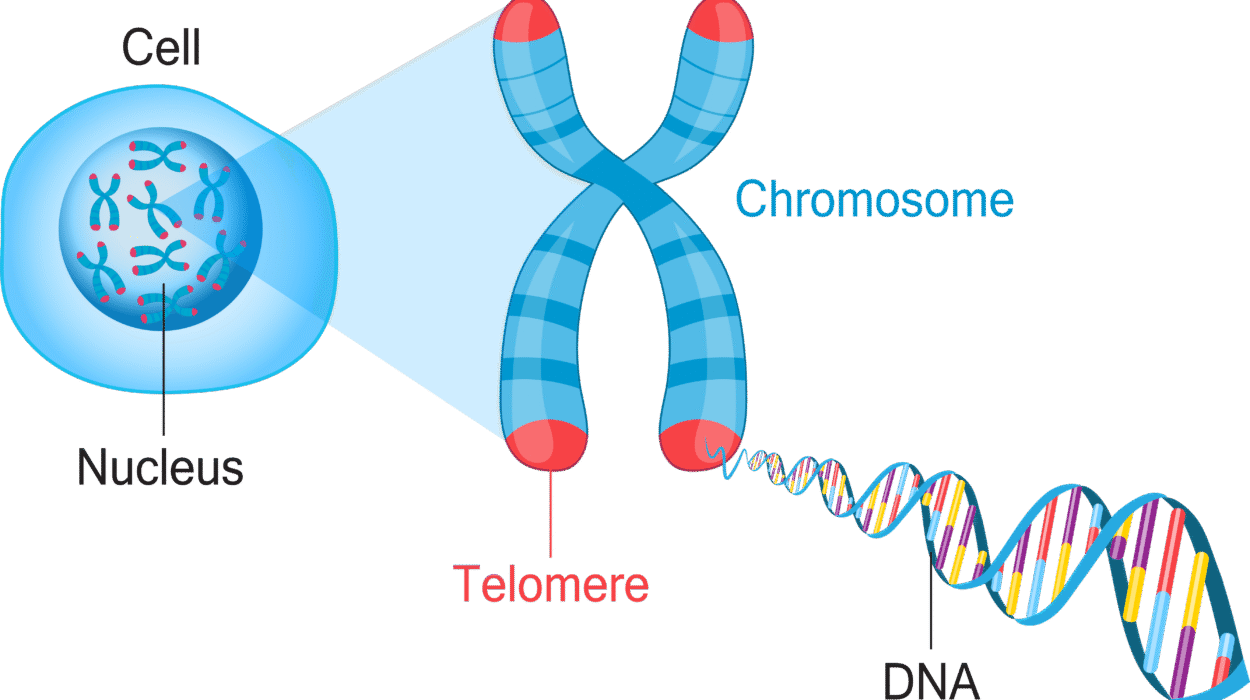

If fossils tell us what early humans looked like, DNA tells us how they were related. The human genome is a treasure trove of information, revealing our connections not just to Neanderthals and chimpanzees, but to every living organism on Earth.

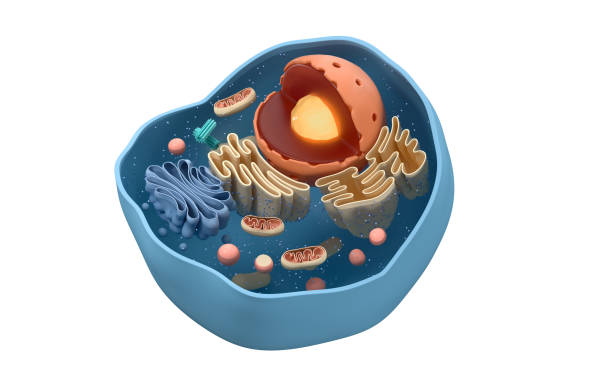

All life shares a common genetic language. From bacteria to elephants to humans, the code of DNA ties us together in one vast, branching tree of life. Humans did not spring fully formed from the earth. We are the product of billions of years of evolutionary experimentation—an unbroken chain of life stretching back to the first cells.

DNA shows that the differences between humans and other apes are small compared to our similarities. Yet those small differences—tiny variations in genes controlling brain development, speech, and social behavior—have made all the difference.

Evolution Is Still Happening

Human evolution did not stop when civilization began. In fact, it continues today. Genetic changes are still occurring, driven by culture, technology, diet, and disease.

For example, the ability to digest lactose (milk sugar) into adulthood evolved in populations that domesticated animals. Resistance to malaria has shaped genes in parts of Africa. The ongoing co-evolution of humans and our environments means that the story of evolution is not over—it’s still being written in our bodies, one mutation at a time.

This understanding dispels the myth of linear progression. Evolution is not a ladder with humans at the top. It is a branching tree with many paths, most of which have ended in extinction. We are not the goal of evolution; we are simply one of its many outcomes—remarkable, yes, but not inevitable.

Why the Confusion Persists

If the science is so clear, why does the misconception that “humans evolved from monkeys” persist?

Part of the confusion lies in language. Words like “descended” or “evolved from” imply a direct line, as if monkeys turned into humans. In reality, humans and monkeys share a more distant ancestor. But that ancestor was neither a modern monkey nor a modern human.

Education systems sometimes fail to explain this nuance. Popular culture adds to the misunderstanding with cartoons showing apes morphing into upright men. These images oversimplify a process that took millions of years and countless transitional forms.

Religious and cultural beliefs also play a role. Some people reject evolution because they feel it conflicts with their spiritual worldview. But many religious traditions have found ways to reconcile faith with science, seeing evolution not as a threat but as a testament to the grandeur of life.

The Beauty of Our Shared Origins

Ultimately, asking whether humans evolved from monkeys is like asking whether birds evolved from dinosaurs. It misses the deeper truth—that all life is connected through time.

The story of human evolution is not one of disconnection from animals, but of deep kinship. It reminds us that we are part of nature, not separate from it. That we carry within us the legacy of ancient forests, of creatures that climbed trees and walked the savanna. That our intelligence, empathy, and creativity did not emerge from nothing, but were shaped by the same forces that sculpted wings, fins, and flowers.

Understanding this story does not diminish our humanity—it enriches it. It gives us a sense of belonging not just to a nation or a culture, but to life itself.

The Answer, at Last

So, did humans evolve from monkeys?

No—humans did not evolve from modern monkeys. We and modern monkeys share a common ancestor that lived millions of years ago. That ancestor was a primate, probably resembling neither a human nor a monkey exactly, but giving rise to both lineages. Monkeys continued down one path. We took another.

The real answer is far more astonishing than a simple yes or no. It is a tale of survival, adaptation, and transformation that spans eons. It is a journey from microscopic beginnings to thinking beings capable of wondering where we came from.

We are not descended from monkeys. We are cousins. We are kin. And we are the storytellers of evolution, shaped by it—and now, finally, able to tell its tale.