For centuries, the bond between humans and sled dogs has been a cornerstone of survival in the harsh, icy expanses of the Arctic. These loyal companions, with their thick fur coats and unyielding strength, have traversed some of the most inhospitable landscapes on Earth. They have hauled heavy loads, pulled sleds over vast distances, and kept their human counterparts alive in an unforgiving world.

Yet, as the Arctic’s icy landscape shrinks and modern technology takes over, one of the most iconic symbols of this ancient partnership—the Greenland sled dog, or Qimmeq—faces an uncertain future.

The once-vibrant population of these remarkable dogs has been cut in half over the past two decades, with numbers dwindling from 25,000 to just 13,000 in 2020. Now, a groundbreaking study is shedding light on the history and genetic diversity of these dogs—revealing not just their origins, but also the deep, intertwined relationship they share with the people of the Arctic.

The Journey Across the Arctic

The story of the Greenland sled dog is as much about the people of the Arctic as it is about the dogs themselves. The Qimmit are one of the few sled dog breeds still fulfilling their traditional role of pulling sleds across Greenland’s snowy expanses. Unlike other breeds like the Siberian husky and Alaskan malamute, which have largely transitioned to pets or companion animals, the Qimmit have remained steadfast in their original purpose.

These dogs’ loyalty and resilience have helped the Inuit people of Greenland survive the challenges of the Arctic for over 1,000 years. But with the decline of sea ice, increased urbanization, the rise of snowmobiles, and changing lifestyles, the Qimmit’s traditional role has been increasingly threatened. Their numbers have dropped sharply in recent years, leading to widespread concern about their future.

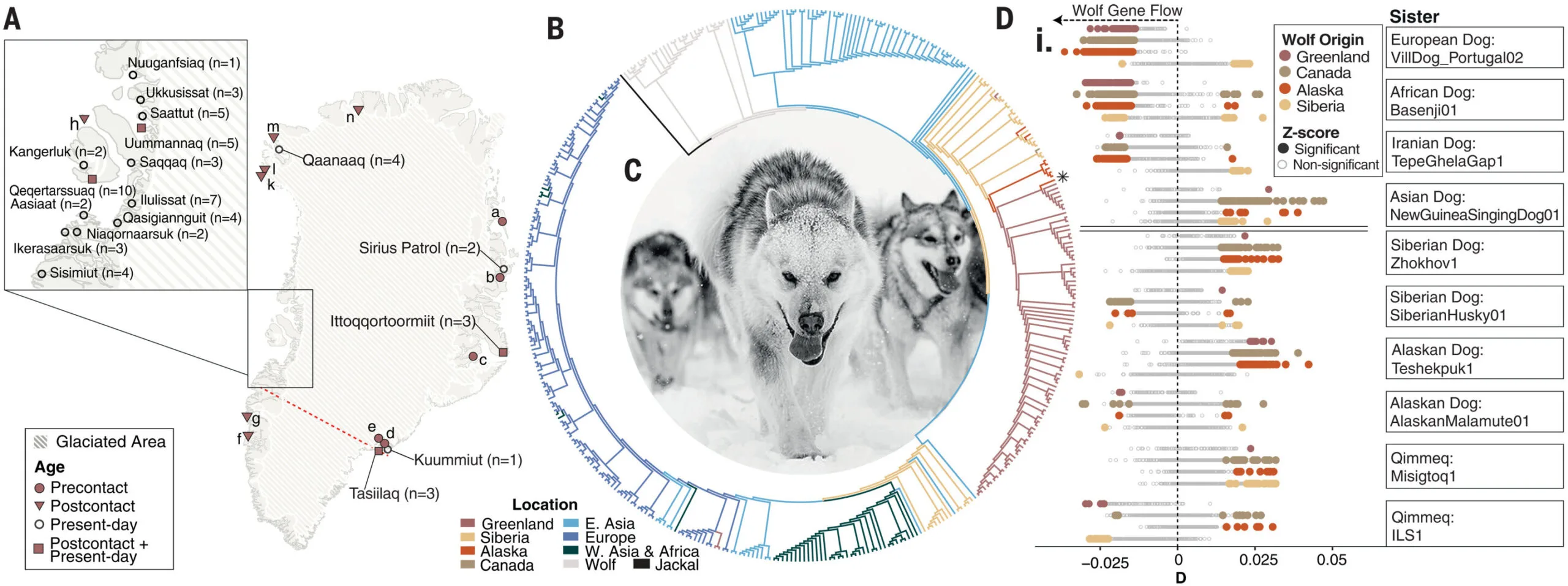

The urgency surrounding their decline spurred researchers from the National Human Genome Research Institute at the National Institutes of Health to delve deep into the genetics of these iconic dogs. The study, which analyzed 92 Qimmit genomes from the past 800 years, offers new insights into the ancient migrations of both the Inuit people and their loyal sled dogs.

Decoding the Past: Two Migrations, One Legacy

Published in Science, the study used advanced genetic sequencing to compare the genomes of the Qimmit to those of ancient and modern dogs and wolves. The researchers separated the genomes into three groups: pre-European contact (before 1721), post-European contact (from 1885 to 1998), and present-day genomes (after 1998). These distinctions allowed them to track the influence of European colonization and better understand how the Qimmit’s genetic makeup has evolved over time.

What they found was nothing short of remarkable. The genetic markers in the Qimmit place their arrival in Greenland much earlier than previously believed—around 1,000 years ago. This finding suggests that the Inuit, along with their sled dogs, migrated across the Arctic Circle far more rapidly than once thought. The close genetic relationship between the Qimmit and an Alaskan breed, dating back to around 3,700 years ago, indicates that these dogs traveled with the Inuit as they moved across the Arctic from Alaska to Greenland.

In a fascinating twist, the study also suggests that the Inuit may have arrived in Greenland before the Norse settlers. Though the Norse established settlements in southwestern Greenland after 985 CE, the study authors note that interactions between the Inuit and Norse people remain unclear. What is evident, however, is that the Inuit—and their sled dogs—were the first to make Greenland their home.

A Genetic Isolation

Perhaps one of the most intriguing findings of the study is the genetic isolation of the Qimmit. While Greenland was colonized by the Danish and Norwegian people, the Inuit and their sled dogs remained largely untouched by European genetics. The study found only minimal traces of European ancestry in the Qimmit genomes, signaling that the dogs—and their human counterparts—remained genetically distinct from the colonizers.

However, the study also revealed significant changes in the Qimmit populations following the Danish-Norwegian colonization of Greenland. Much like the indigenous peoples of Greenland, the Qimmit began to diverge into distinct regional groups, a reflection of the cultural shifts that occurred within Greenland’s human populations. This divergence mirrors the development of unique subcultures among Greenland’s indigenous peoples, each group adapting to its local environment and way of life.

Cultural and Conservation Implications

The findings underscore the cultural significance of the Qimmit, not just as working animals, but as integral partners in the history of the Inuit people. These dogs are more than just tools—they are a living link to a past that has shaped the people of Greenland and the Arctic. Their decline is not only an ecological issue but a cultural one, representing the loss of a partnership that has endured for over a millennium.

With the changing climate and increasing globalization, the future of the Qimmit looks uncertain. Researchers hope that their genetic findings will provide the necessary tools for developing conservation strategies aimed at preserving this unique breed. Understanding the Qimmit’s genetic history is crucial to safeguarding their future, especially as their traditional role in Greenland’s harsh environment becomes increasingly irrelevant in the face of technological advancements like snowmobiles.

The study also raises important questions about the broader impacts of climate change on Arctic ecosystems and the species that depend on them. As the ice continues to recede and human settlements expand, the delicate balance of life in the Arctic is being disrupted—not just for people, but for the animals that have lived alongside them for thousands of years.

The Enduring Bond: Humans, Dogs, and the Arctic

The story of the Qimmit is more than a tale of sled dogs; it is a story of survival, resilience, and adaptation in one of the harshest environments on Earth. For thousands of years, these dogs and their human companions have shared a bond that has transcended generations. Their history is intertwined, their fates linked by the icy landscapes of the Arctic.

As we look to the future, it is crucial to remember that the fate of the Qimmit is tied not only to the survival of their breed but to the survival of the cultural and environmental heritage of the Arctic itself. In a rapidly changing world, it is vital to preserve the legacy of these dogs and their human partners—not just for the sake of history, but for the sake of future generations.

Reference: T. R. Feuerborn et al, Origins and diversity of Greenland’s Qimmit revealed with genomes of ancient and modern sled dogs, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adu1990