In the cold, windswept mountains of Mongolia, where snow-capped peaks meet endless steppes, the ancient art etched into stone tells stories of a world long past. Amidst these captivating images—of animals, humans, and landscapes—one species stands out: the elk. Once depicted in meticulous detail, these magnificent creatures have been immortalized on the rock faces of the Altai Mountains. But over time, something extraordinary happened to their depiction. What began as lifelike portrayals slowly transformed, becoming more abstract, until the elk was no longer recognizable as the animal we know today, but something else entirely—an enigmatic, wolf-like creature.

What caused this dramatic shift in artistic representation? Dr. Esther Jacobson-Tepfer, an esteemed archaeologist, delves into this transformation in her latest study published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal. Her research illuminates not just the evolution of elk rock art but also the environmental and socio-political forces that may have influenced these changes, leading to a deeper understanding of ancient human societies in the Mongolian Altai.

Elk: Majestic Creatures of the Altai Mountains

Elk, the second-largest members of the Cervidae family after moose, once roamed the vast, wild forests of the Eurasian steppe. Their large antlers, which males shed annually, were not just a remarkable natural feature—they became an important cultural symbol for the people who lived alongside them.

Elk are mixed feeders, living on a diet of grasses and browse, which made them particularly adapted to forested environments or areas at the edges of forests. The Altai Mountains, rich in biodiversity and steeped in ancient history, were one such environment where elk thrived and became integral to the landscape—and to the cultures that inhabited the region.

The earliest depictions of these majestic creatures date back to the late Paleolithic period, about 12,000 years ago, when prehistoric humans first began to carve images of elk into rock. While painted images may have existed, they have not survived the harsh climate of the Altai, where the elements have erased all but a single painted depiction, found in the Khoit Tsenkir cave in Khovd, just south of Bayan Ölgiy.

“These early elk depictions are remarkable for their realism,” Dr. Jacobson-Tepfer explains. “The art was created with a keen observation of the natural world, capturing the elk in profile with their striking antlers, and often in the company of other animals, such as mammoths, woolly rhinos, and ostriches.”

The Transition: From Realism to Stylization

As the centuries passed, elk imagery began to evolve. Early representations were static and realistic—showing elk in profiles with their legs depicted in simplified forms, suggesting a direct realism. But this depiction began to change.

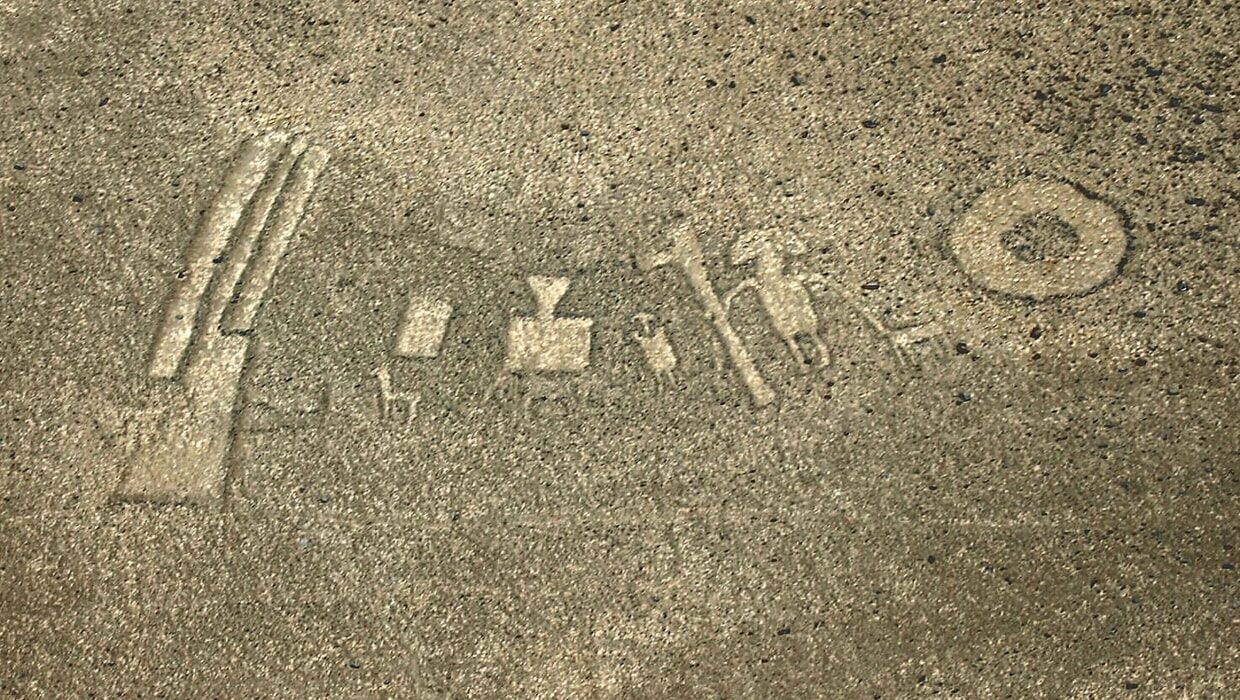

By the time of the Bronze Age, around 3,000 years ago, elk art started to become more stylized. Artists elongated the bodies of elk and exaggerated their antlers, moving away from the grounded realism of earlier periods. As time wore on, this stylization grew more exaggerated, with elk being rendered with elongated, almost fantastical features: their faces now resembled bird beaks, and their bodies took on the shape of distorted, wolf-like beasts.

Dr. Jacobson-Tepfer traces these radical transformations to significant changes in the environment and social structures of the region, offering insight into how external forces may have altered not just the landscape, but the very way people saw and represented the world around them.

The Changing Environment and Its Impact on Society

As the Holocene period unfolded, the Eurasian steppe began to shift in its climate. The once lush and forested landscapes gradually became cooler and drier, which led to the retreat of forests that elk had once roamed. This environmental change caused elk to move westward and northwest, pushing them away from their traditional territories.

The human societies living alongside them had to adapt as well. As forests receded, people followed the herds, moving higher into the mountains in search of new hunting grounds. Simultaneously, as these ancient peoples increasingly turned to pastoralism, they became more semi-nomadic, adapting their lifestyles to the challenges of a changing climate.

Dr. Jacobson-Tepfer highlights this shift, explaining how rock art reflects this movement: “We begin to see art that depicts families traveling with their herds, and rock art sites appear at progressively higher elevations, indicating the migration of human groups into more rugged terrains.”

The adaptation of horses into pastoral life was another significant turning point. Initially used as pack animals, horses soon became essential for mounted riding, which further transformed the social dynamics of these societies. As people moved further from their natural environments, there was a corresponding shift in their art. Mounted individuals began to dominate the imagery, often decorated with stylized motifs of elk and other animals.

This shift points to an increasing emphasis on personal and group identity, likely tied to the emergence of social hierarchies and the growing significance of herding and riding cultures.

Elk as Symbols of Power and Identity

As the elk’s portrayal became increasingly abstract, it took on new meanings. What had once been a simple representation of a powerful animal evolved into a symbol of power, prestige, and perhaps even ritual importance. Elk were no longer depicted solely as part of the natural world but were incorporated into human culture, representing clan identity and personal status.

“The transition from realistic elk images to stylized depictions suggests that elk were no longer merely a reflection of the natural world,” Dr. Jacobson-Tepfer argues. “They were now symbols, perhaps denoting status or group affiliation in the context of shifting social structures.”

By the time of the Turkic Period, the elk had completely disappeared from rock art, replaced by other symbols and motifs that resonated with the societies of the time. But the transformation of elk imagery speaks to something deeper—the way art, like society, evolves in response to changing circumstances.

The Disappearance of the Elk Image

The disappearance of elk in the rock art of the Mongolian Altai by the Turkic Period marks the end of an era. From their realistic portrayal as part of the natural landscape to their final transformation into fantastical, wolf-like creatures, the elk’s representation mirrored the profound transformations in the environment, society, and culture of the Altai’s ancient peoples.

In a world where art was often intertwined with survival and identity, these changes in elk rock art are more than just a shift in aesthetics—they reflect the adaptability of human societies, their relationship with the land, and their evolving social structures.

As Dr. Jacobson-Tepfer concludes, “By studying the evolution of elk in rock art, we gain more than just insight into artistic techniques—we uncover a history of adaptation, transformation, and the ever-changing relationship between people and the world they inhabit.”

Reference: Jacobson-Tepfer, E. From Monumental Realism to Denatured Beast: The Transformation of the Elk Image in Rock Art of the Altai Mountains (Mongolia) and its Cultural Implications. Cambridge Archaeological Journal (2025). DOI: 10.1017/S0959774325000137