Long before humans began rewriting the landscape with highways and cities, Earth was shaped by creatures of breathtaking size and power. Mastodons tromped through forests in search of tender shoots. Giant deer, with antlers stretching wider than a man is tall, clashed on the grassy plains. Towering rhinos, some as tall as giraffes, thundered across savannas, carving trails into the earth that may have lasted for centuries. These were not merely impressive spectacles of ancient life—they were the architects of ecosystems, the green world’s gardeners, engineers, and guardians.

Large herbivores, those massive plant-eating mammals whose bulk often exceeded a ton, have played an unsung but foundational role in Earth’s ecological history. They broke branches, toppled trees, churned soil, dispersed seeds, and fertilized land with vast amounts of dung. They determined which plants thrived and which didn’t, how water flowed through a landscape, and which predators followed in their wake. And for millions of years, through mass extinctions and climatic upheavals, they helped ecosystems persist and adapt.

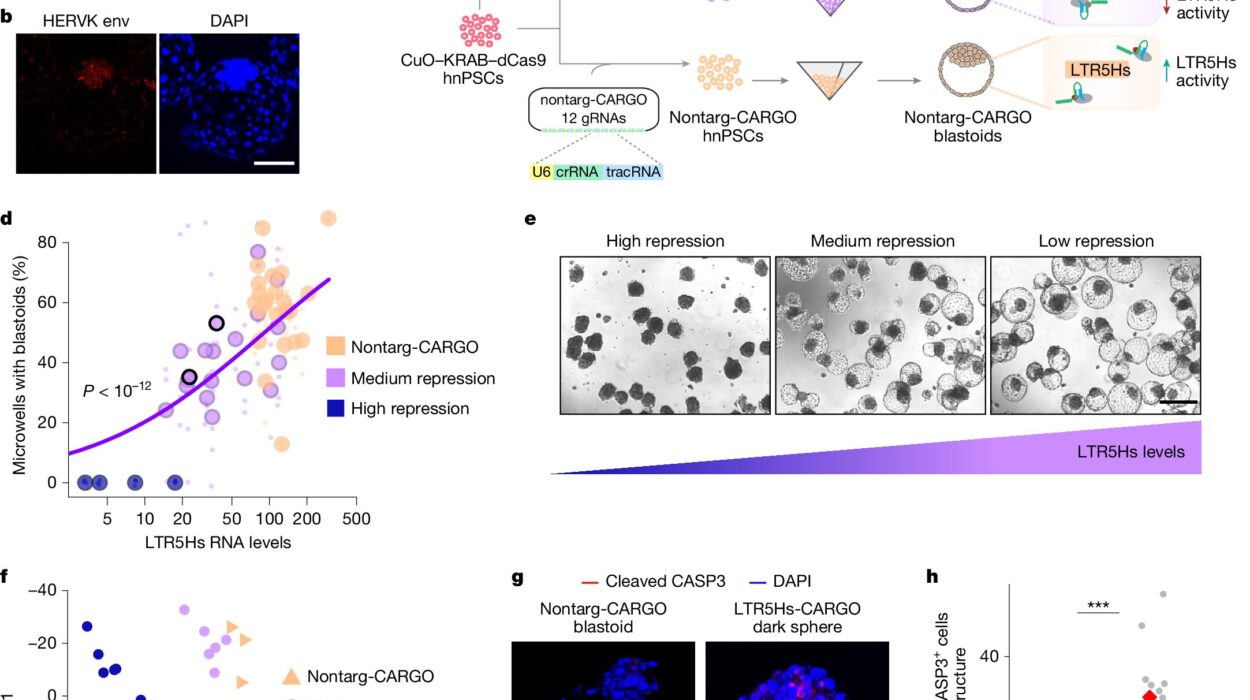

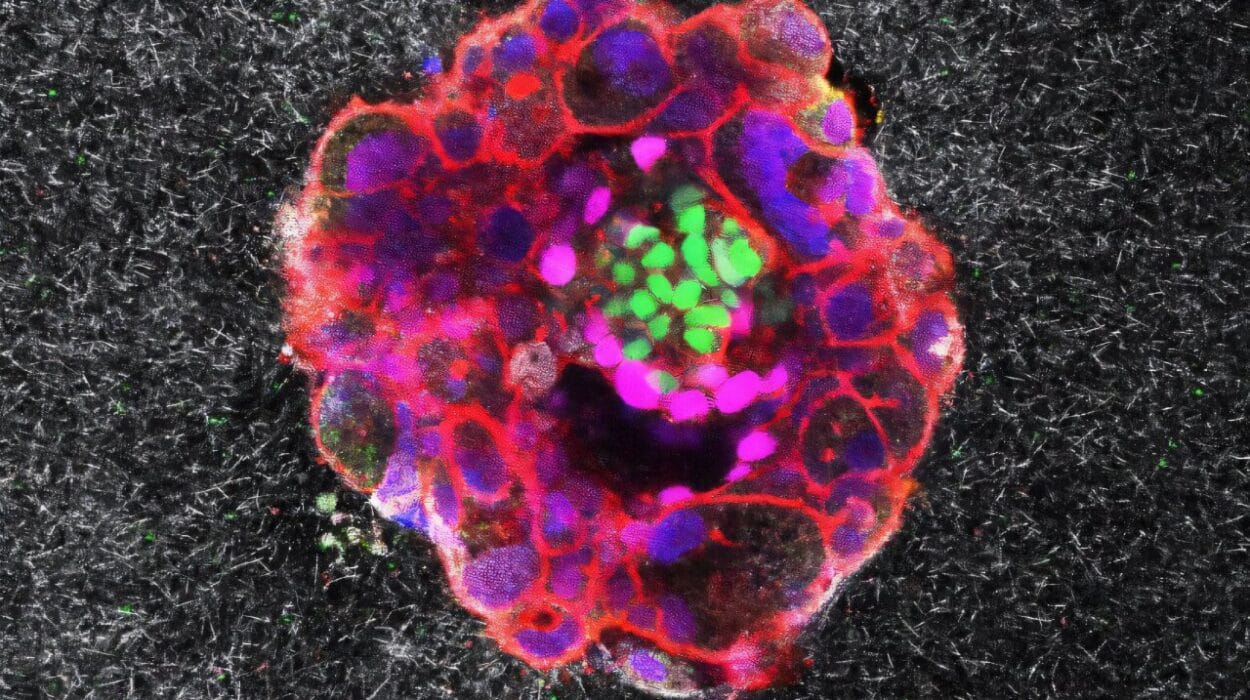

Now, a groundbreaking study published in Nature Communications reveals just how resilient—and vulnerable—these ancient communities have been. By analyzing the fossil records of over 3,000 large herbivore species spanning 60 million years, an international team of scientists has traced the shifting fortunes of Earth’s herbivore giants. Their conclusion: while the players changed, the game—the structure of ecosystems—often remained surprisingly intact.

Until, that is, the world changed too fast.

Resilience Through Chaos

To piece together the story of these ecosystem engineers, researchers combed through fossil data spanning the entire Cenozoic era, the geological chapter that began shortly after the dinosaurs’ extinction. This 60-million-year window includes dramatic moments in Earth’s history—periods when oceans receded, continents collided, volcanoes erupted, and ice sheets crept from the poles. In each of these times, herbivores were not simply passive victims. They responded dynamically to the shifting stage beneath their feet.

“We found that the large herbivore ecosystems stayed remarkably stable over long periods of time, even as species came and went,” explained Fernando Blanco, lead author of the study and a paleobiologist formerly at the University of Gothenburg. “Species disappeared, new ones evolved or migrated in—but the basic ecological structure was preserved. That kind of resilience is incredible.”

This finding runs counter to the assumption that mass extinctions or sudden environmental shifts lead to total ecological collapse. Instead, large herbivore communities seem to possess a built-in adaptability. Like a symphony where the instruments change but the melody continues, their ecosystems maintained balance through substitution.

Yet, there were two moments—two tectonic shifts in Earth’s natural order—when that melody was interrupted.

The First Great Shake-Up: Land Bridges and Migrations

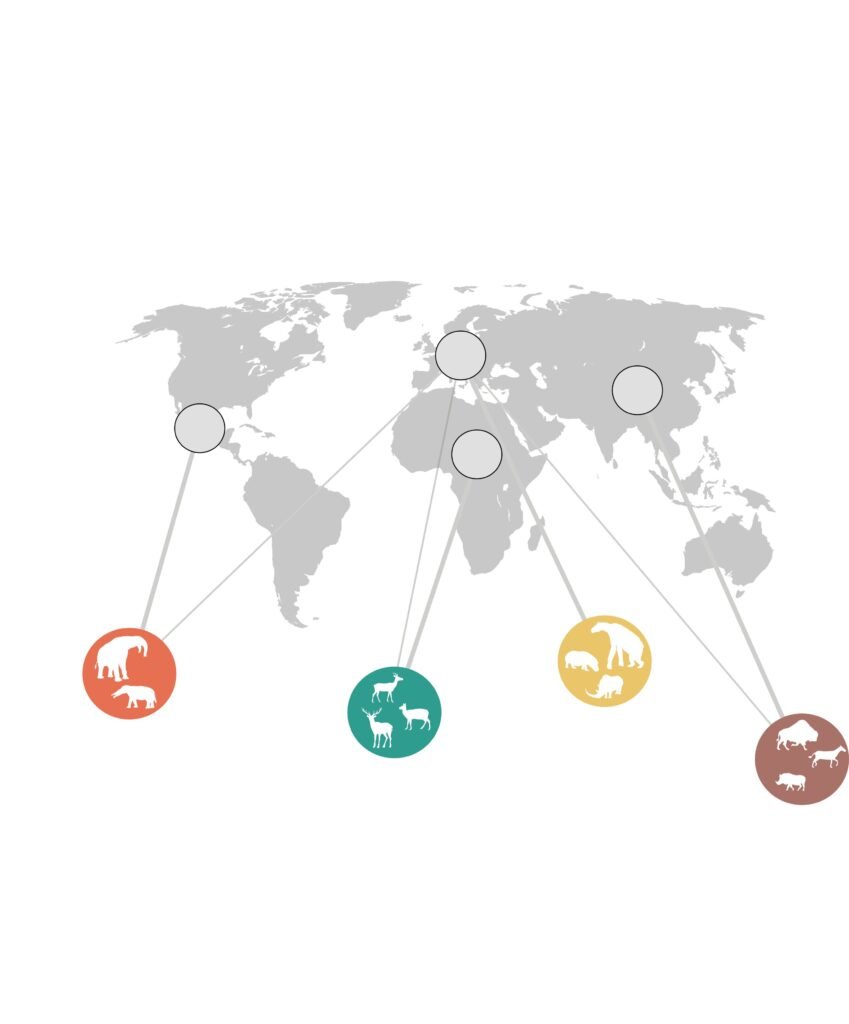

Roughly 21 million years ago, Earth’s surface was in flux. What had been a great seaway—the Tethys Ocean—was slowly pinched closed by the drifting of the African and Eurasian plates. As mountains rose and the sea vanished, a land corridor formed, connecting Africa with Europe and Asia.

This geologic rearrangement unleashed a biological revolution.

The new land bridge acted as an open invitation to African herbivores, unleashing a wave of migrations northward. Among the first to cross were the ancestors of modern elephants—massive tusked beasts that brought with them their own ecological preferences and disturbances. But they weren’t alone. Deer, pigs, giraffids, antelopes, and rhinos surged across the continents, competing with native species and reshaping the plant life wherever they settled.

For the first time, a true planetary mixing of large herbivore lineages occurred, and the resulting ecological disruption led to an evolutionary arms race. Plants developed tougher defenses; animals evolved stronger teeth and more specialized digestive systems. It was a time of ecological innovation and destruction—a reshuffling of the deck that would define much of the later Miocene epoch.

This migration frenzy was not gentle. Many endemic species went extinct, unable to compete or adapt quickly enough to the new arrivals. But out of the chaos, a new stability emerged. The balance of roles—browsers versus grazers, small-bodied versus giants—was maintained, even if the cast of characters was forever changed.

A World Growing Colder and Harsher

দ্বিতীয় মহান পরিবেশগত টিপিং পয়েন্টটি প্রায় ১ কোটি বছর আগে এসেছিল। এবার, এটি টেকটোনিক ছিল না – এটি ছিল বায়ুমণ্ডলীয়। পৃথিবীর কক্ষপথ, সমুদ্র স্রোত এবং কার্বন চক্রের পরিবর্তনের ফলে বৈশ্বিক তাপমাত্রা দীর্ঘ সময়ের জন্য হ্রাস পেতে শুরু করে। হিমবাহ তৈরি হওয়ার সাথে সাথে এবং মেরু অঞ্চলের বরফের চাদর প্রসারিত হওয়ার সাথে সাথে, গ্রীষ্মমন্ডলীয় বনগুলি সংকুচিত হয়ে যায়, খোলা সাভানা এবং তৃণভূমি দ্বারা প্রতিস্থাপিত হয়।

This environmental pivot favored a different kind of herbivore. Where once slow-moving browsers thrived in dense forests, now nimble grazers took over, adapted to wide-open spaces and tough, silica-rich grasses. Teeth got longer and stronger, legs lengthened for speed, and herds became larger and more migratory.

With the rise of grasslands came the extinction of many forest specialists. The diversity of ecological roles—known as functional diversity—began to narrow. Even though herbivores continued to roam in abundance, they filled fewer ecological niches. The orchestra, while still playing, lost several instruments.

But remarkably, the researchers found that the structure of these communities—the essential organization of ecological functions—held steady. Even as climate transformed ecosystems on every continent, large herbivores kept doing what they had always done: churning, trampling, fertilizing, pruning.

“It’s like a football team changing players during a match but still keeping the same formation,” said Ignacio A. Lazagabaster, co-author and researcher at CENIEH in Spain. “Different species came into play and the communities changed, but they fulfilled similar ecological roles, so the overall structure remained the same.”

Endurance in the Face of Ice and Fire

Over the past 4.5 million years, Earth has cycled through repeated ice ages and warm periods—each a fresh trial for ecosystems already under pressure. Yet even through these upheavals, large herbivore communities continued to display astonishing resilience.

The Ice Age megafauna, those charismatic creatures whose fossils still inspire wonder—woolly mammoths, giant ground sloths, saber-toothed cats—thrived during this time. And though many of them vanished in waves of extinction beginning around 129,000 years ago, particularly after human expansion into new continents, ecosystems managed to hang on. The roles of seed dispersers, grass trimmers, and forest architects were passed along, sometimes to smaller or more adaptable species.

In some regions, elephants took over where mammoths fell. In others, bison or deer became the dominant grazers. Ecological redundancy—the idea that different species can perform the same role—acted as a buffer, preserving ecosystem integrity even as extinction thinned the ranks.

Yet this buffer may not last forever.

A Third Tipping Point on the Horizon

The message from the fossil record is clear: Earth’s ecosystems are resilient, but not invincible. The current extinction crisis, fueled by human-driven habitat loss, overhunting, and climate change, is accelerating at a pace unprecedented in geological history. Unlike past disruptions that unfolded over millennia, today’s ecological changes are happening in mere decades.

“Our results show that ecosystems have an amazing capacity to adapt,” noted Juan L. Cantalapiedra, senior author of the study and a researcher at MNCN in Spain. “But the rate of change is so much faster this time. There’s a limit. If we keep losing species and ecological roles, we may soon reach a third global tipping point, one that we’re helping to accelerate.”

This looming crisis differs from the previous ones not only in speed but also in scope. Human activity is not confined to one region or continent; it touches nearly every ecosystem on Earth. Where once nature had time to shuffle the deck and rebuild, today’s rapid-fire extinctions leave little room for recovery. Functional diversity—the ecosystem’s safety net—is being shredded.

Many modern ecosystems now run on a skeleton crew. African elephants, once widespread across the continent, now face poaching and habitat loss that threaten to sever their role as keystone architects. Rhinos, once abundant grazers and seed dispersers, are on the brink. Even deer populations in some areas are artificially inflated due to the absence of predators, creating feedback loops that degrade forests and grasslands.

Lessons from the Deep Past

Yet the fossil record does not only offer warnings—it offers wisdom. These ancient systems endured change not because they were static, but because they were flexible. When one species disappeared, another evolved, migrated, or adapted to fill its place. This functional redundancy was key to long-term stability.

For modern conservation, this insight is profound. Protecting biodiversity isn’t just about saving rare or charismatic species—it’s about preserving the functions they perform. It’s about understanding which roles are vital for ecosystem health and ensuring that enough species exist to carry those roles forward.

It also underscores the importance of rewilding—the reintroduction of key species to landscapes where they’ve been lost. Projects like returning bison to American plains, wild horses to Eurasian steppes, or even elephants to degraded forests are more than symbolic acts. They’re attempts to restore the ancient rhythms of life that sustained the planet for millennia.

And perhaps most importantly, the fossil record reminds us that Earth is not passive. It reacts. When ecosystems lose complexity, they become brittle. When they fall apart, rebuilding them takes millions of years—far beyond a human lifetime.

The Ghosts Still Whisper

Walk through a savanna or forest today, and you can still hear echoes of that ancient world. In the ways elephants knock down trees, in the grazing patterns of wildebeest, in the paths carved by deer or boar—you glimpse the persistence of an ecological structure built long before humans walked upright.

But those ghosts grow quieter every year.

If we continue on the path of species loss, we risk silencing them forever. The structure of life that has persisted through ice ages and tectonic upheavals could finally buckle—not from natural forces, but from human negligence.

Yet, hope remains.

We are the first species capable of understanding this vast ecological history and the first with the power to change its course. By protecting what remains and restoring what’s lost, we may yet ensure that the great herbivores—and the ecosystems they anchor—can continue to shape the Earth, just as they have for 60 million years.

Reference: Fernando Blanco et al, Two major ecological shifts shaped 60 million years of ungulate faunal evolution, Nature Communications (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41467-025-59974-x