In the limestone quarries of Bavaria and Baden-Württemberg, Germany, fossils whisper stories of ancient seas. Layered within the famed Plattenkalk deposits—rock formed from shallow lagoons nearly 150 million years ago—scientists have uncovered an extraordinary new chapter in the history of life on Earth.

A team led by Martin Ebert of the Ludwig Maximilian University and Adriana López-Arbarello of the Unidad Ejecutora Lillo has identified a completely new species of fish from the Jurassic, a predator that swam swiftly through warm European seas when dinosaurs ruled the land. Their study, recently published in the Swiss Journal of Palaeontology, not only expands our understanding of a remarkable group of prehistoric hunters but also reveals how evolution can sometimes take unexpected, even short-lived, turns.

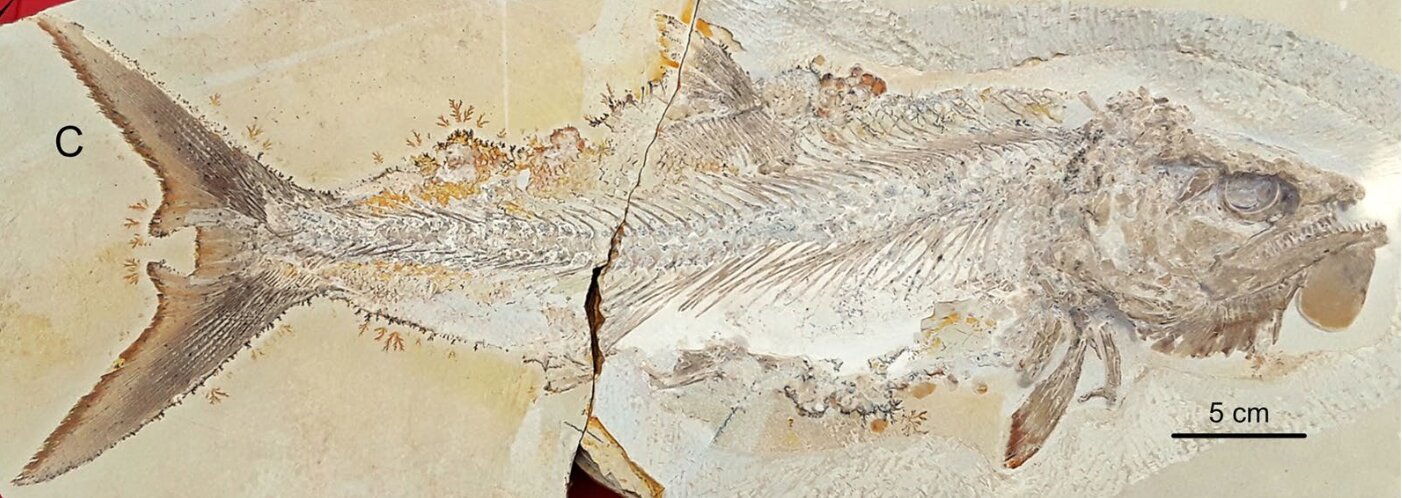

The fish belongs to the family Caturidae, a lineage of fast, predatory swimmers that thrived during the Jurassic. Known for their sleek forms and sharp teeth, caturoids were perfectly adapted to chase smaller prey in shallow seas. Until now, 14 Jurassic species of Caturus were known. But the newly described species—Caturus enkopicaudalis—stands apart with unique traits that make it unlike any of its kin.

A Tail Unlike Any Other

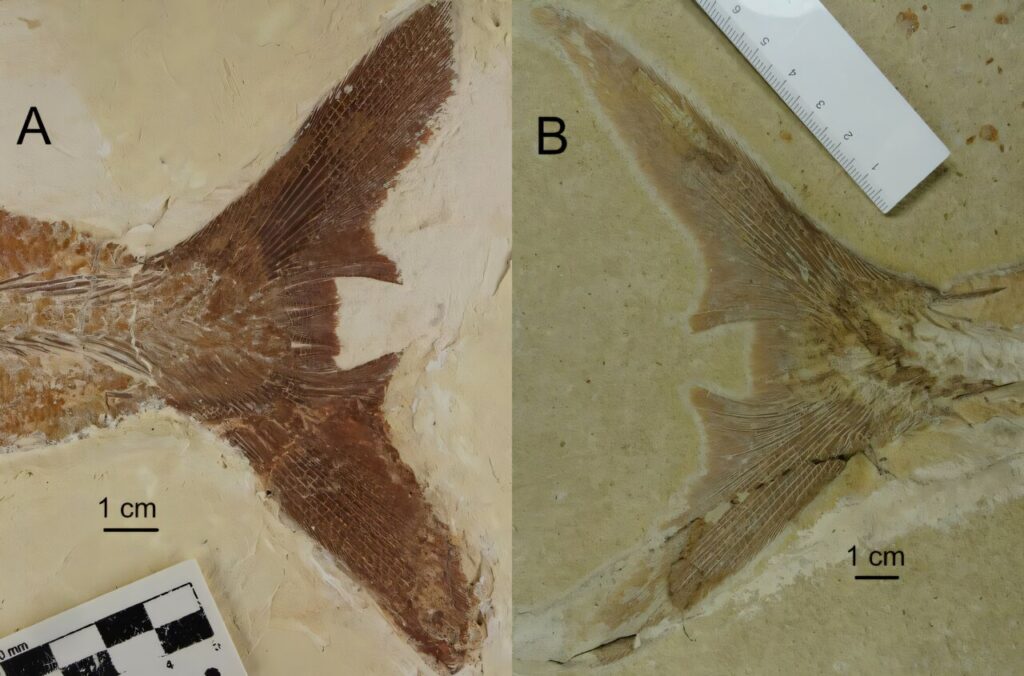

At first glance, Caturus enkopicaudalis might not appear dramatically different from other caturids. But its tail fin tells a very different story. Instead of the typical streamlined forked tail seen in most of its relatives, this species bore a peculiar double-notched design—a forked fin with a plateau in the middle, almost as if the tail had been carved into steps.

Where other caturoids had tails shaped for efficiency and sustained speed, this new species’ tail suggests a different strategy. The central plateau was supported by three or four short, broad rays—an unusual arrangement in the family. This gave the fin a “stepped” look, a distinctive mark that inspired its name: enkopicaudalis, from the Greek word enkopí (notch) and caudalis (tail).

But why such an odd adaptation? Professor David Bellwood, a marine biologist not involved in the study, speculates that this tail might have been an evolutionary gamble—an innovation that offered advantages in quick, explosive bursts of speed but lacked efficiency for long-distance swimming. Such an adaptation could have helped in ambush hunting or chasing prey in cluttered habitats but may have ultimately proven unsustainable. “I suspect it was an evolutionary innovation that did not stand the test of time,” Bellwood noted, suggesting the trait may have been either a specialized adaptation to a new niche or a maladaptation that survived only briefly.

Armor of Scales

If the tail was not enough to set Caturus enkopicaudalis apart, its body armor seals its uniqueness. Most Caturus species carried between 51 and 56 rows of ganoid scales—diamond-shaped, enamel-like plates that shimmered like armor. This new species, however, possessed an astonishing 91 to 99 rows, nearly double the usual number.

These scales were relatively small, smooth, and tightly arranged, particularly around the caudal fin. Unlike the ordered ganoin patterns found in its relatives, Caturus enkopicaudalis exhibited unordered scales, making it the only Jurassic species of its genus with this trait. The combination of a high scale count and unusual distribution suggests this fish may have been more heavily protected than its relatives, possibly to withstand predators or the physical demands of its environment.

A Predator’s Smile

Like its kin, Caturus enkopicaudalis was equipped with sharp, pointed teeth designed for predation. Its maxilla (upper jaw) was long and slender, holding 33 teeth, while the dentary (lower jaw) carried 25. Two of these lower teeth were significantly larger than the rest—three times the length of the maxillary teeth—creating a fearsome bite. Such dentition suggests a diet of smaller fish and marine creatures, which it likely pursued with sudden bursts of speed, aided by its unusual tail.

Adding to its distinctive profile was its gular plate, the bony structure beneath the jaw. In this species, it was among the widest of all known caturids, reinforcing its unique anatomy.

Windows into an Ancient Sea

The fossils that revealed this predator were collected from the Upper Jurassic Plattenkalk basins of the Solnhofen Archipelago in Bavaria and the Nusplingen Plattenkalk of Baden-Württemberg. These sites are world-famous fossil treasure troves, preserving delicate creatures in exquisite detail—everything from dragonflies to the feathered dinosaur Archaeopteryx. The fine limestone captured life as it was, leaving behind fossils that still breathe stories into the present.

The discovery of Caturus enkopicaudalis underscores the incredible diversity of caturids during the Jurassic. With their slender bodies, sharp teeth, and swift movements, they were apex hunters of their time, dominating shallow seas while reptiles soared overhead and dinosaurs thundered across the land.

The Fragility of Evolution

The strange case of Caturus enkopicaudalis offers a powerful reminder: not all evolutionary experiments endure. Its unusual tail may have been a bold innovation, one that gave it an edge for a time but ultimately left it at a disadvantage compared to its relatives. By the Lower Cretaceous, the family Caturidae itself was in decline, with only three species surviving before vanishing completely.

This story of fleeting adaptations resonates far beyond paleontology. Evolution is not a straight path of progress—it is a branching tree full of experiments, successes, and failures. Some traits persist for millions of years; others appear briefly and vanish, leaving only fossilized echoes for us to discover.

Why Discoveries Like This Matter

The identification of Caturus enkopicaudalis adds one more piece to the puzzle of life’s history. Each new species we uncover deepens our understanding of how ecosystems functioned in the past and how life adapted to changing environments. Fossils like these are not just relics of stone; they are keys to understanding resilience, extinction, and the unpredictable creativity of evolution.

Moreover, this discovery highlights the importance of careful museum research. The fossils studied by Ebert and López-Arbarello had been resting quietly in collections for decades. Only now, with modern analysis, have they revealed their secrets. It is a reminder that scientific treasures often lie hidden, waiting patiently for fresh eyes and new questions.

A Glimpse Into the Jurassic Sea

To imagine Caturus enkopicaudalis alive is to picture a shimmering predator darting through warm lagoons, its stepped tail propelling it toward unsuspecting prey. Armored in ganoid scales, armed with sharp teeth, it was a master of its domain. And yet, despite its prowess, it ultimately vanished, leaving behind only fossilized traces of its brief evolutionary path.

The sea it once swam is gone, transformed into stone. But with every fossil discovery, we breathe life back into these forgotten creatures, piecing together the story of our planet’s ever-changing tapestry. Caturus enkopicaudalis is not just a name in a journal—it is a reminder that evolution is full of wonders, many of which we have yet to discover.

More information: Martin Ebert et al, A new species of the genus Caturus (Caturidae, Amiiformes) from the Upper Jurassic of the Solnhofen Archipelago (Germany), Swiss Journal of Palaeontology (2025). DOI: 10.1186/s13358-025-00383-4