Hungarian, Finnish, and Estonian—three languages spoken in the heart of Europe—stand out like ancient monuments in a modern landscape. Their cadence, grammar, and structure are vastly different from the French, German, and Slavic languages that dominate the continent. Linguists have long known they belonged to the Uralic language family, but no one could say for sure where that family began.

Until now.

Thanks to groundbreaking genetic research that peered back through more than 11,000 years of human history, scientists have discovered something astonishing: the roots of Uralic languages lie not near Europe at all, but deep in northeastern Siberia—closer to Alaska than to Helsinki.

This revelation doesn’t just rewrite the story of a language family; it reshapes our understanding of how small, ancient communities once stretched their influence across thousands of miles, leaving linguistic fingerprints on the forests and frontiers of a continent.

Ancient DNA, Modern Breakthroughs

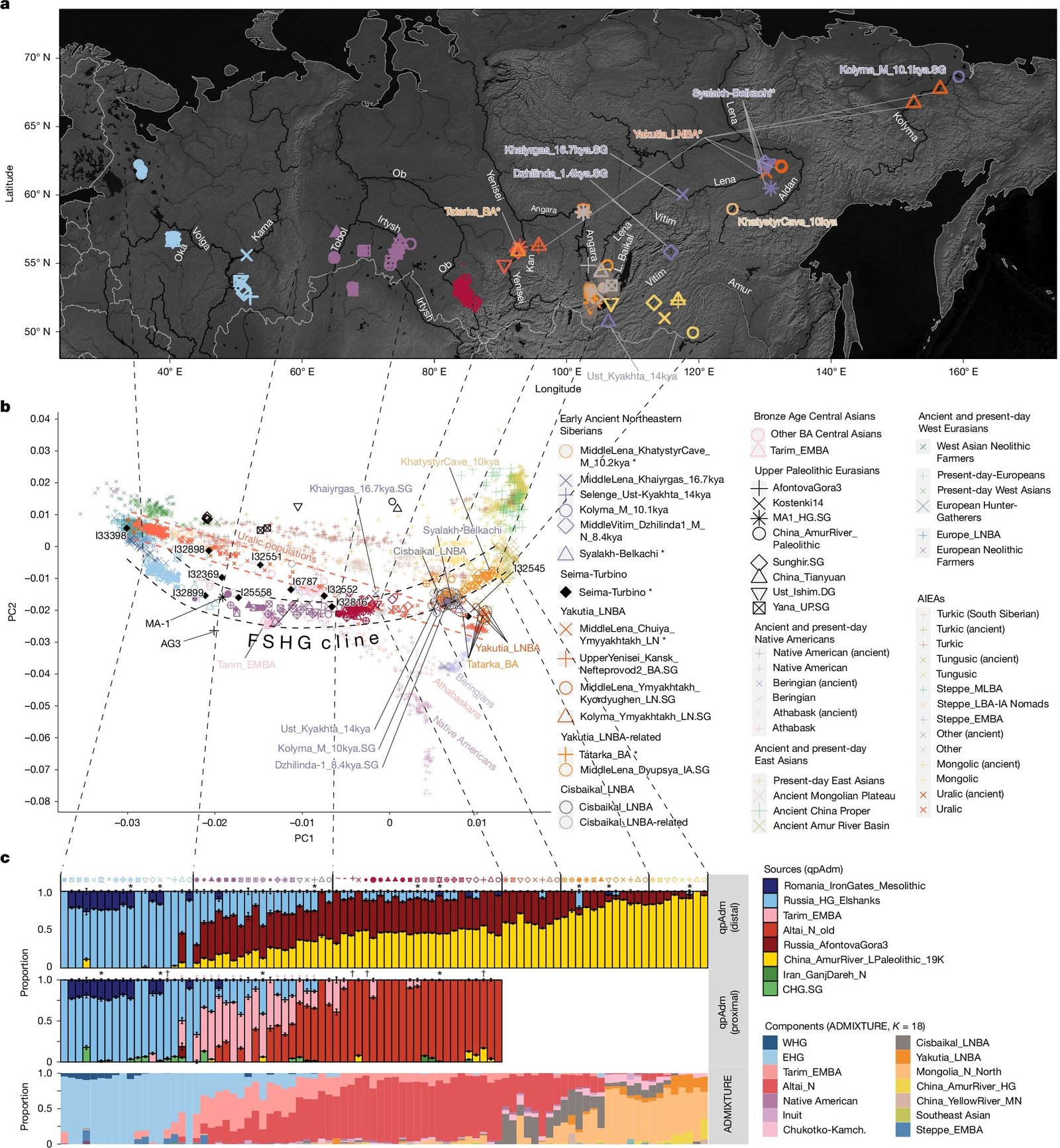

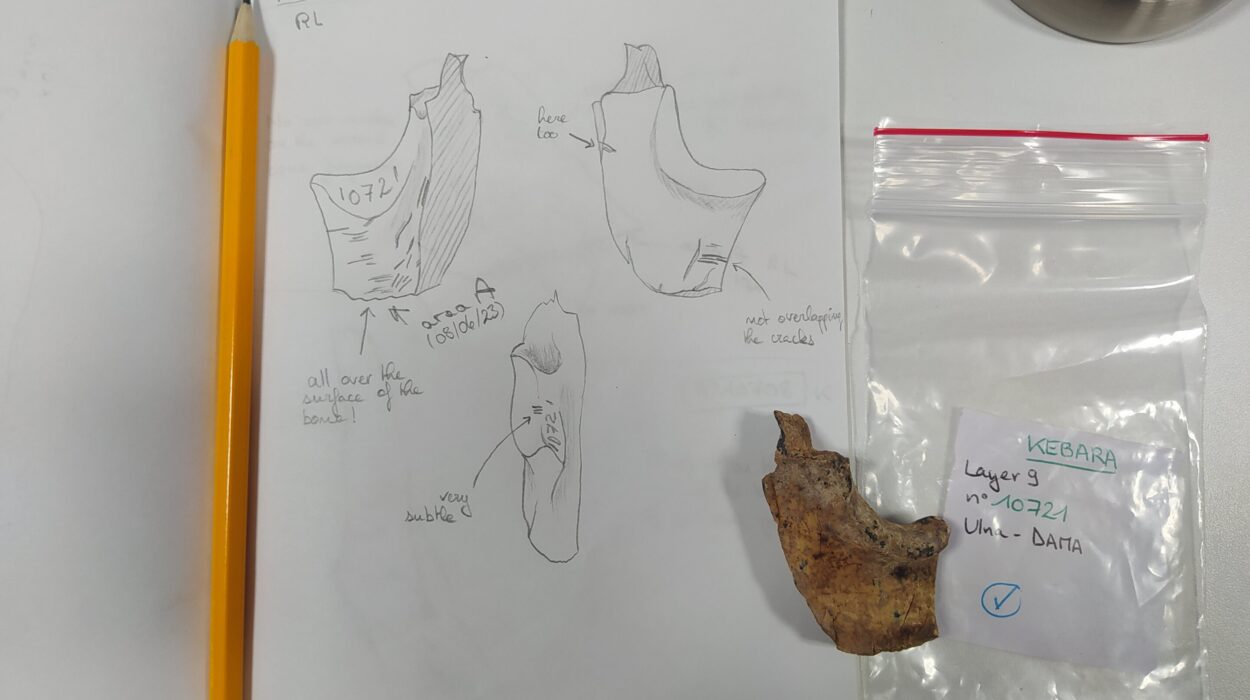

The answers emerged from the icy soils of Siberia, where researchers extracted ancient DNA from human remains dating back 4,500 years. This genetic data, combined with more than 1,000 previously sequenced genomes from across Eurasia, formed a sweeping mosaic of human ancestry.

At the heart of this effort were two young researchers—Taliah Chen Zeng and Alexander Mee-Woong Kim—working with renowned ancient DNA expert David Reich at Harvard. Together, they traced the genetic signature of early Uralic-speaking peoples to a place few had thought to look: Yakutia, a vast, remote expanse of boreal forest in northeastern Siberia.

From that frigid homeland, the echoes of Uralic speech would eventually spread westward across the taiga, reaching as far as the Baltic Sea and the Hungarian plains.

A Tale of Two Language Families

Human history is not just a sequence of migrations and wars—it’s also the movement of words, syntax, and song. For decades, scientists have studied the Indo-European family—the group that includes English, Russian, Hindi, and dozens more. They traced its origins to the grasslands of modern Ukraine, where the Yamnaya culture of horseback herders began spreading its influence over 5,000 years ago.

But while Indo-European languages galloped across the steppe, Uralic languages crept through the forests. And their origins were no less dramatic.

The team’s genetic analysis revealed a striking pattern: modern Uralic-speaking populations, from the Sámi people of Scandinavia to the Nganasan people of Arctic Russia, carried a genetic signal linked to ancient Yakutians. This signal—undetectable in other language groups—showed up consistently, though at different levels, depending on how far west each group lived.

This suggested that a small population of Siberian foragers, equipped with unique language and culture, had slowly moved westward—leaving traces in genes, languages, and the very names of rivers and mountains.

Forged in Bronze, Carried by Climate

The spread of Uralic languages wasn’t just a quiet cultural drift. It likely coincided with one of the most fascinating episodes in ancient Eurasian history: the Seima-Turbino phenomenon.

Around 4,000 years ago, something remarkable happened across the northern forests of Eurasia. Technologically advanced bronze tools, weapons, and artifacts suddenly appeared across a vast region—often found buried with individuals from many different genetic backgrounds. This wasn’t a military empire or a single migrating tribe. It was a shared technology, leaping across enormous distances, uniting small groups into broader networks.

The rise of bronze wasn’t just a leap in metallurgy. It demanded raw materials like tin and copper, which were rare and widely scattered. To use bronze, societies had to build trade networks, form alliances, and develop new kinds of cooperation. For the communities who spoke early Uralic languages, these changes may have acted as a cultural catalyst—spreading their influence faster and farther than would otherwise be possible.

Zeng, who led the DNA data analysis, believes these new social connections likely provided Uralic speakers with the means to carry their language and culture across the taiga. And unlike the horse-riding Yamnaya of the south, Uralic peoples thrived in dense forests, frozen lakes, and northern tundra. Their resilience helped them carve out linguistic territory in a rugged, unforgiving landscape.

Whispers from the Ice: The Genetic Trail

The study uncovered a genetic breadcrumb trail, stretching westward from Yakutia to Finland, Estonia, and beyond. In the far northeast, the Nganasan people still carry almost 100% of the Yakutia ancestry—a living window into the genetic makeup of Proto-Uralic speakers.

As one moves west, the signal fades. Finns retain about 10% of this ancient ancestry, while Estonians have just 2%. Modern Hungarians, however, have almost none. Yet when scientists analyzed DNA from the medieval conquerors who brought the Uralic language to Hungary, the Yakutia signal was clear. The genes had faded—but the language survived.

This tells us something remarkable about language transmission: it doesn’t always require population replacement. Small groups, through cultural prestige, resilience, or social structure, can leave behind a linguistic legacy far more durable than their genetic one.

The Yeniseian Echoes and a Vanishing Tongue

While exploring the Uralic puzzle, the researchers also stumbled onto another thread—a more fragile, fading one.

In central Siberia, a language called Ket clings to life among a handful of elderly speakers. It belongs to the Yeniseian language family, once spoken across a much larger region. Though it teeters on the brink of extinction, Ket holds secrets that may reshape our understanding of ancient migrations across the Bering Strait.

Linguist Edward Vajda has proposed a bold theory: that Yeniseian languages are distantly related to Na-Dene languages spoken by Indigenous peoples in Alaska and parts of Canada. If true, this would suggest a deep connection between ancient Siberian and North American peoples, possibly dating back more than 10,000 years.

The genetic findings in the new study offer tentative support. Traces of ancestry near Lake Baikal, dated to around 5,400 years ago, may align with the early homeland of the Yeniseian family. Toponyms—place names—in Turkic and Mongolic regions still bear hints of Yeniseian roots, much like how “Mississippi” and “Missouri” reflect Algonquian heritage in the U.S.

Even as Ket fades, its linguistic and genetic legacy whispers across landscapes where it has not been spoken for centuries.

The Forest Speaks: A Legacy of Resilience

What emerges from this research is a story not of domination, but of endurance. Uralic-speaking communities were never numerically dominant, never imperial forces. They were small bands of hunters, foragers, and later farmers, surviving in some of the harshest climates on Earth. Yet their words, carried in song and memory, persisted across the centuries.

In a world increasingly shaped by migrations, empires, and upheaval, the Uralic languages are a testament to the quiet power of culture. They moved not with armies, but with families. They spread not through conquest, but through contact, trade, and the soft bonds of community.

Kim, an archaeologist with a deep interest in Siberia and Central Asia, puts it simply: “This is a story about the will, the agency of populations who were not numerically dominant in any way but were able to have continental-scale effects on language and culture.”

The legacy of these Siberian travelers still lives in the grammar of Estonian, the vowel harmony of Hungarian, and the lullabies of the Sámi. And now, through ancient DNA, we hear their story more clearly than ever before.

A New Frontier in Human History

This research is not the final word. It is a door opening.

With every new ancient genome, scientists gain another thread in the tapestry of human history. Language, genetics, and archaeology are no longer isolated disciplines—they’re joining hands to tell stories that were once locked in ice and forgotten in forest shadows.

As more data arrives from under-studied regions and cultures, the history of language families like Uralic and Yeniseian will only grow richer. We may find more linguistic islands, more forgotten ancestors, more unlikely journeys.

What we now know is this: the Uralic languages are not just survivors of time. They are testaments to resilience, shaped by people who braved the coldest forests, mastered new technologies, and carried their culture across a continent—one word at a time.

Reference: Tian Chen Zeng et al, Ancient DNA reveals the prehistory of the Uralic and Yeniseian peoples, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09189-3