Long before the first spark of civilization, long before agriculture or even storytelling as we know it, humans were already shaping culture through the most primal of acts—preparing food. Now, tens of thousands of years later, buried beneath layers of earth and time, subtle traces of this human behavior are whispering their secrets to archaeologists.

Deep in the heart of what is now northern Israel, nestled within the ancient caves of Amud and Kebara, two groups of Neanderthals once passed their winters. Though separated by only 70 kilometers and equipped with nearly identical stone tools, these prehistoric humans processed their meals in ways so distinct, so ritualized, that scientists now suspect they may have been passing down their own forms of culinary tradition.

New research led by Anaëlle Jallon, a Ph.D. candidate at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem, reveals compelling evidence that Neanderthal groups at Amud and Kebara practiced different butchery techniques—differences that may not be random at all, but rather reflective of culture, habit, and possibly even taste. “The subtle differences in cut-mark patterns between Amud and Kebara may reflect local traditions of animal carcass processing,” Jallon explains. “They seem to have developed distinct butchery strategies, possibly passed down through social learning and cultural traditions.”

Could it be that Neanderthals—often dismissed as brutish, unsophisticated beings—had something akin to family recipes?

Bones Speak Louder Than Words

Between 50,000 and 60,000 years ago, when glaciers crept across Europe and the Levant, and predators roamed more freely than people, Neanderthals sought shelter in the stone chambers of Amud and Kebara. These caves would have offered warmth, safety, and community—a place to sleep, make tools, raise children, and prepare food.

The archaeological remains from both sites tell us these groups had much in common. Both hunted similar game, mostly fallow deer and gazelles. Both used flint blades shaped by skilled hands. Both left behind the charred evidence of fires where stories may have been shared in some form, and meals surely were.

But under the microscope, archaeologists began to notice a strange pattern. Though the tools were the same, the way they were used on animal carcasses was not. The bones at Amud bore cut-marks that were more densely packed, more curved, more varied in angle. At Kebara, the marks were more spaced out, more linear, more systematic. Even when scientists focused on the exact same types of bones from the same kinds of animals, the differences persisted.

It was not a matter of prey choice or available resources. The evidence didn’t point to desperation or improvisation. What emerged instead was the ghost of intention—a sign of habit, of decision-making, of method. And perhaps, of identity.

Cultural Choice or Culinary Craft?

For decades, scholars debated whether Neanderthals had culture in the way modern humans do. They knew how to make fire, buried their dead, and possibly even painted. But what about the things we don’t often write about—the quiet rituals that fill the spaces of daily life? Could these beings, so often mischaracterized as dull-witted cavemen, have passed down food preparation practices from one generation to the next?

The evidence suggests yes. Not only did Amud Neanderthals process bones differently, but their approach remained consistent across time, suggesting a standardized technique rather than improvisation. This is key. Consistency implies teaching. It implies observation. It implies that someone, somewhere, showed another how to slice in a particular way—and that way became the way.

Such habits echo the essence of cultural transmission. It’s how traditions form: not through utility alone, but through memory, repetition, and belonging. Whether it’s a grandmother’s stew recipe or the way a community smokes meat in the winter, food often becomes a language of continuity. It speaks to what a group values, how it adapts, and what it cherishes.

“We wanted to explore whether Neanderthal butchery techniques were standardized,” Jallon says. “If they varied between sites or time periods, that would suggest cultural traditions, cooking preferences, or social organization played a role—even in something as utilitarian as food processing.”

Not Just Bones, But Behavior

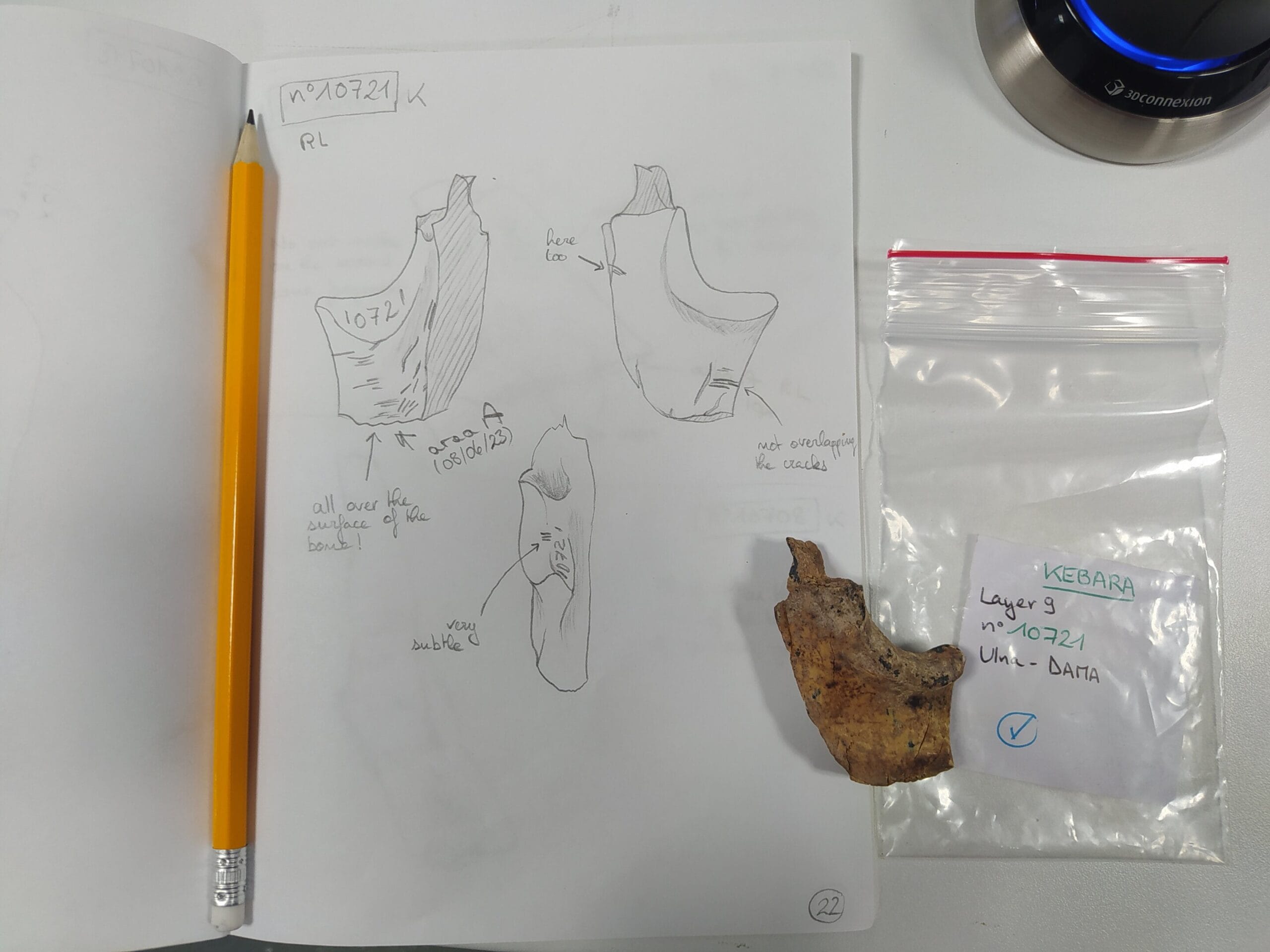

To reach their conclusions, Jallon and her colleagues selected and examined a sample of cut-marked bones from contemporaneous layers in Amud and Kebara. These bones came from the same species, dated to the same general period, and had been preserved under comparable conditions.

They studied the cut-marks both macroscopically—using the naked eye—and microscopically, analyzing shape, depth, profile, and distribution. The similarities in toolkits meant that any differences likely stemmed from behavior rather than hardware. Sure enough, Amud’s bones showed tighter clusters of cut-marks and more variability in the direction of slicing.

These weren’t the chaotic results of inexperience. If anything, they hinted at advanced decision-making. The Amud group may have been handling meat that had been hung, dried, or aged—a process not unlike how modern butchers allow meat to rest to improve flavor and texture. Aged or partially decomposed meat becomes tougher to cut, which could explain the more forceful, overlapping slices.

Another possibility, the researchers note, is that more individuals participated in butchering at Amud, leading to a less linear style. Perhaps food processing there was more communal, while at Kebara it was more specialized. Either scenario implies a level of social organization rarely attributed to Neanderthals—and forces us to rethink how we see them.

Fire, Fragmentation, and the Hidden History of Taste

The story doesn’t end with cut-marks. Fire, too, played a role in shaping the archaeological record—and perhaps the taste preferences of ancient humans. At Amud, nearly 40% of the bones were burned, and most were highly fragmented. This could mean many things: intense cooking, roasting, even bone-boiling to extract marrow. At Kebara, only 9% of bones showed burning, and fewer were broken into small pieces.

Once again, the divergence suggests a difference in approach. At Amud, cooking may have been more intensive, or the community might have extracted every last bit of nutrition from their food—breaking bones open for marrow and fat. Or perhaps they liked their meat more thoroughly cooked. Maybe roasting large chunks of bone-laden meat over an open flame was more common there, while Kebara preferred a quicker method, with smaller portions cooked lightly and more cleanly.

Of course, these patterns also might reflect differences in resources or environment, but the overall consistency and the lack of evidence for necessity-driven changes lean toward a more fascinating explanation: taste, tradition, and a sense of how food should be treated.

What Recipes Might Have Meant to a Neanderthal

We may never know exactly how Neanderthals seasoned their meat, if at all, or how they portioned meals among their community. But the butchery techniques revealed in this study offer something more profound than ingredients. They suggest that food, even then, was not merely survival—it was social.

In this light, the image of a Neanderthal family gathered around a fire gains new depth. The cave walls are warmed by flickering flames. The air is rich with the scent of cooked meat. A young member of the group watches an elder expertly cut along a familiar path, just as they’ve done many times before. There is rhythm, muscle memory, and maybe even storytelling in those movements. These are not the acts of an unthinking brute, but of someone taught, someone learning, someone remembering.

And what is a recipe, if not a memory passed from hand to hand?

The Limits of the Bones—and the Promise of the Future

As with all archaeology, there are limitations. The bones themselves are often incomplete, broken by time or by ancient hands. Jallon acknowledges this: “While we have made efforts to correct for biases caused by fragmentation, this may limit our ability to fully interpret the data. Future studies, including more experimental work and comparative analyses, will be crucial for addressing these uncertainties.”

Yet even within these limits, the implications are astonishing. If different Neanderthal groups had distinct butchery traditions, that suggests cultural variation—local customs passed down through generations. It also means that behaviors we once believed belonged only to Homo sapiens were already being practiced by our evolutionary cousins.

Perhaps one day, more sophisticated studies will allow researchers to go even further: reconstructing the full choreography of an ancient meal, or even identifying residue from herbs or wild flavorings. For now, it is enough to know that Neanderthals—so long caricatured as crude and unfeeling—may have cared deeply about how they prepared their food.

A Taste of Humanity Across the Ages

In these ancient cut-marks, we glimpse not just biology, but humanity. These are the quiet fingerprints of culture—the slow, patient shaping of behavior through love, habit, and tradition.

The Neanderthals of Amud and Kebara lived tens of thousands of years ago. They are gone now, their languages silenced, their songs (if they had them) lost to the wind. But they have left behind a kind of recipe—not written in ink or carved in stone, but etched in bone and preserved in time.

And in that recipe lies a message we’re only just beginning to understand: that culture begins not with cathedrals or novels, but with the simple, sacred act of preparing food to share with others.

Reference: Cut from the same cloth? Comparing Neanderthal processing of faunal resources at Amud and Kebara caves (Israel) through cutmarks analyses, Frontiers in Environmental Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.3389/fearc.2025.1575572