In the farthest reaches of the Northern Hemisphere lies a world defined by extremes. The Arctic is a domain carved from ice and shadow, where temperatures plunge below -40°C, sunlight disappears for months, and blizzards scream across vast tundras. To human eyes, it is an uninhabitable wasteland. Yet beneath its frozen veneer, the Arctic teems with life—resilient, ingenious life that has evolved over millennia to withstand what may be Earth’s most punishing environment.

In this forbidding land, every heartbeat and breath is an act of survival. Creatures from the colossal polar bear to the delicate Arctic tern exhibit biological adaptations so remarkable they appear sculpted by some ancient artist with a meticulous hand. These animals are more than survivors; they are masterpieces of evolutionary engineering. Their stories are not only scientific marvels but also poetic testaments to life’s unyielding desire to endure, adapt, and flourish against all odds.

The Architecture of Warmth: Fur, Fat, and Feathers

At the core of Arctic survival is the relentless battle against heat loss. Warm-blooded animals, known as endotherms, must maintain a constant internal temperature despite external conditions that would freeze flesh in minutes. To do this, Arctic species have evolved extraordinary physical adaptations that insulate, protect, and preserve every precious degree of body heat.

Mammals like the Arctic fox and polar bear are cloaked in fur that is not merely thick but also structurally specialized. The Arctic fox boasts one of the densest pelts in the animal kingdom. Its winter coat is so effective at trapping heat that it can sleep on the ice without shivering. This insulation is due to the complex layering of underfur and guard hairs that form a microclimate around the body, drastically reducing heat loss.

Polar bears take insulation to a higher level. Beneath their fur lies a layer of black skin that absorbs solar heat, and beneath that, a thick pad of subcutaneous fat—up to 11 centimeters deep. This fat not only stores energy but serves as a thermal blanket, enabling the bears to swim in near-freezing water and travel long distances across ice sheets.

Birds like the snowy owl and the ptarmigan rely on feathers, but not the delicate kind found in temperate species. Arctic birds grow down feathers so dense they resemble cotton wool. These feathers trap warm air close to the skin and are often accompanied by a counter-current heat exchange system in their legs that minimizes heat loss through extremities. In the ptarmigan’s case, feathers even grow along its feet, forming a natural pair of snowshoes and extra insulation against the frostbitten ground.

Blood That Defies the Cold

If fur and fat are the armor of Arctic creatures, then blood is their furnace. But even the heartiest circulatory system is vulnerable to the laws of thermodynamics. Heat escapes quickly through limbs and extremities, so many Arctic animals have developed ingenious physiological mechanisms to prevent this.

A common adaptation is counter-current heat exchange. In species such as reindeer, Arctic wolves, and seabirds like gulls, arteries and veins run side by side in the limbs. Warm arterial blood flowing from the body heats the colder venous blood returning from the extremities. This system ensures that by the time blood reaches the surface tissues, it is cooler, minimizing heat loss, while maintaining core temperature.

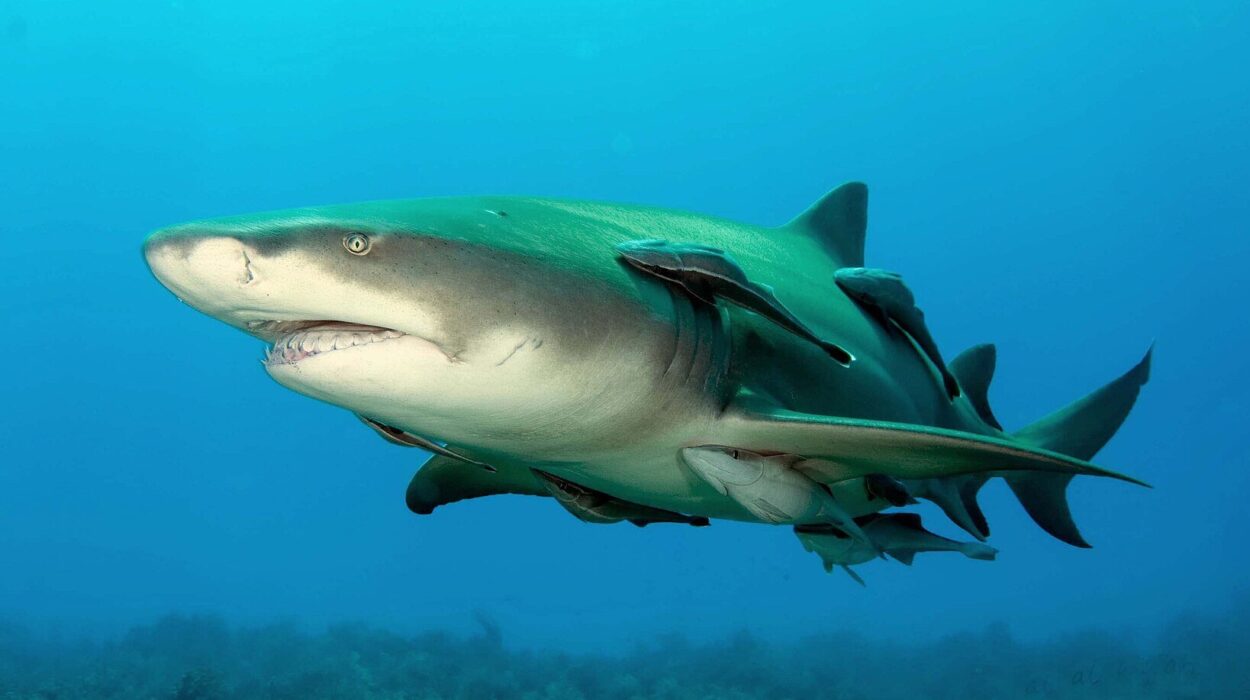

But some Arctic dwellers go even further. The Greenland shark, one of the most mysterious inhabitants of the frigid North Atlantic, has blood rich in special proteins called trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) that stabilize its enzymes against the cold. TMAO acts as an antifreeze and counteracts the destabilizing effects of urea, allowing this enormous fish to function in temperatures near freezing while living for hundreds of years.

Insects like the Arctic woolly bear moth employ a biochemical marvel known as cryoprotection. They produce natural antifreeze compounds such as glycerol and sorbitol that prevent ice crystal formation within cells. These larvae can survive being frozen solid and thawed—sometimes for over a decade—emerging to complete their life cycle during one brief summer.

The Strategy of Stillness

While many animals adapt by increasing metabolic activity or insulating themselves against the cold, others take a radically different approach: they do nothing at all. Instead of fighting the environment, they enter a state of physiological suspension—essentially becoming one with the ice.

The Arctic ground squirrel, for example, hibernates not just in body but in mind. During its torpor, this small rodent lowers its core body temperature to as little as -2.9°C, effectively becoming the coldest known mammalian hibernator. Its heartbeat drops to a few beats per minute, and brain activity all but ceases. Yet remarkably, the animal suffers no lasting damage. Scientists believe that this extreme hibernation may hold the key to understanding human hypothermia and neuroprotection during strokes or surgery.

Other creatures engage in behavioral torpor or temporary inactivity. The polar bear, particularly pregnant females, will den in snow caves for months at a time, reducing their metabolic rate and surviving solely on fat reserves. Despite their immense size, they emerge from this fasting period with newborn cubs and sufficient energy to begin hunting anew.

Color That Changes With the Seasons

The Arctic is not always white. For a few weeks each year, it bursts into a brief, dazzling summer, blanketing the tundra with mosses, flowers, and migrating insects. For animals, this shift is not just ecological—it’s visual. Camouflage becomes critical in both winter’s whiteout and summer’s color-rich landscape, and so some Arctic species have evolved the astonishing ability to change color with the seasons.

The Arctic hare, the stoat, and the ptarmigan undergo seasonal molting. In winter, their coats are pure white, blending seamlessly into the snow. As the snow melts and the earth reemerges, their pelage or plumage turns brown, grey, or speckled—matching the rocky tundra and scrub.

This adaptive camouflage is more than just aesthetic. It reduces predation risk and increases hunting success. The molecular signals that trigger these changes are linked to the photoperiod—the length of daylight—which acts as a seasonal cue for hormone production and fur or feather growth.

What’s striking is that this ability isn’t fixed. Climate change and disrupted snow patterns are beginning to expose white-coated animals against brown backdrops. There is growing evidence that some populations are responding with altered molting times or even losing the white coat altogether—a quiet but telling sign of evolutionary pressure unfolding in real time.

Intelligence, Memory, and Migration

Adaptation is not only skin deep. In the Arctic, intelligence and behavioral flexibility are critical to survival, particularly for migratory species that must navigate thousands of kilometers across unforgiving terrain.

The Arctic tern performs the longest known migration of any animal on Earth—traveling from the Arctic to the Antarctic and back each year, a round trip of over 70,000 kilometers. How this delicate seabird, weighing less than a smartphone, navigates such vast distances with precision remains a subject of scientific fascination. Researchers believe that Arctic terns use a combination of visual landmarks, Earth’s magnetic field, celestial navigation, and possibly olfactory cues to complete this monumental journey.

Caribou (reindeer) also undertake epic migrations, moving in herds across tundra plains in search of food and calving grounds. They have an incredible sense of spatial memory and can detect lichen under several feet of snow using their acute sense of smell. Their hooves adapt seasonally—soft and spongy in summer for traction on wet ground, hard and sharp in winter to cut through ice and snow.

Even predators like Arctic wolves exhibit sophisticated social behaviors. Living in tight-knit packs, they coordinate hunts and raise offspring communally. Their success depends not only on physical strength but on cooperation, planning, and communication—traits once thought to be exclusive to primates and humans.

The Underwater Underdogs

The Arctic Ocean, though perpetually capped with ice, is no less biologically diverse than its land-based counterpart. Beneath the surface, a hidden world of marine mammals, fish, and invertebrates has evolved to master the cold in astonishing ways.

The narwhal, with its spiral tusk and ghostly white skin, is adapted to life under ice. Its blood is rich in myoglobin, allowing it to store vast quantities of oxygen and dive to depths exceeding 1,500 meters. Narwhals navigate by echolocation in complete darkness, pinging their surroundings like biological sonars in an aquatic maze of ice and silence.

Beluga whales, often called “canaries of the sea” for their melodic vocalizations, possess a highly flexible neck—unusual among whales—which allows them to maneuver in shallow, ice-laden waters. Their thick blubber and reduced dorsal fin help them retain heat and swim beneath ice sheets without injury.

Fish like the Arctic cod and icefish are perhaps the most chemically adapted of all. These species produce antifreeze glycoproteins that bind to ice crystals in their blood, preventing them from growing and damaging tissues. This adaptation allows them to remain active in waters that would lethally freeze most other fish.

The Fragile Future of Resilience

The Arctic is a bastion of adaptation, but it is not invulnerable. Climate change is transforming this once-stable environment at an alarming pace. Sea ice is retreating, permafrost is melting, and the delicate balance that sustains life in this region is being disrupted. The very adaptations that made Arctic animals successful are now becoming liabilities in a changing world.

Polar bears, once the lords of the ice, are struggling to find hunting platforms as sea ice vanishes. Their primary prey—seals—are becoming harder to catch, leading to nutritional stress, lower cub survival, and increased human-animal conflict. Arctic foxes are being pushed out of their range by the larger red fox, which is expanding northward with warming temperatures.

Migratory birds are arriving out of sync with insect blooms, and reindeer face ice-locked pastures due to rain-on-snow events that freeze lichen under impenetrable layers of ice. Evolution can only work so fast, and the Arctic’s transformation is occurring at a pace unseen in geological history.

Yet, there is still time to act. Understanding these adaptations offers more than academic insight; it reveals the interconnectedness of life, the ingenuity of evolution, and the consequences of human impact. Conservation, research, and sustainable policy are not just ethical imperatives—they are acts of biological stewardship.

Echoes in the Ice

To witness the Arctic is to be humbled. It is to stand at the edge of Earth’s known extremes and realize that life, in all its forms, has found ways to thrive where logic suggests it shouldn’t. The adaptations of Arctic animals are not merely tricks of survival; they are echoes of deep time, shaped by countless generations facing bitter winds and endless night.

Each fur-cloaked predator, each migratory marvel, and each hibernating heartbeat tells a story of triumph. The Arctic is a living chronicle of nature’s capacity for resilience, a frozen symphony of survival that continues to play—though ever more faintly—in a warming world.

The secrets of Arctic adaptations are, ultimately, the secrets of life itself: to endure, to adapt, and to persevere through the fiercest of trials. They remind us that in even the coldest corners of existence, warmth—in body, spirit, and evolution—can prevail.