For most of human history, we assumed our family tree was simple—just us, Homo sapiens, as the final chapter of evolution. But the past few decades have turned that view upside down. New discoveries show that we once shared the Earth with other kinds of humans—our close relatives, who lived, loved, hunted, and raised children long before recorded history. Among these forgotten cousins are the Denisovans, a mysterious group that emerged during the Pleistocene epoch, around 370,000 years ago.

Yet unlike Neanderthals, who left behind dozens of fossils and artifacts, Denisovans remain almost invisible. Only a handful of fossil fragments—part of a finger bone, a jaw, and a few teeth—have been discovered. But thanks to cutting-edge genetic science, we are finally beginning to uncover what these elusive humans looked like and how they fit into our shared evolutionary story.

A Finger Bone That Changed Everything

The Denisovans were first discovered in 2010, and it happened almost by accident. In the cold, remote Denisova Cave in Siberia, archaeologists had unearthed what they believed was a Neanderthal finger bone. But when scientists analyzed its DNA, the results stunned them. The bone didn’t belong to a Neanderthal—or to modern humans. It came from an entirely unknown branch of the human family tree.

This discovery was a turning point. For the first time, an extinct human relative was identified not by its skeleton or tools, but by its genetic code. The Denisovans had remained invisible to archaeology, but their DNA revealed their existence—and hinted that their legacy lived on in us.

The Power of Ancient DNA

Since that first discovery, scientists have sequenced Denisovan genomes and compared them with those of modern humans. What they found was remarkable: people living today, especially in parts of Asia, Oceania, and Australia, still carry Denisovan DNA. In fact, some populations in Papua New Guinea and Melanesia inherit up to 5% of their genome from Denisovans.

This genetic inheritance influences our biology even today. For example, Denisovan genes help modern Tibetans survive at high altitudes by making their blood more efficient at carrying oxygen. These invisible traces remind us that we are not alone—we are the product of encounters and intermingling with other human lineages.

But what did Denisovans look like? Were they tall, broad-shouldered, or perhaps stockier than us? Until recently, that question seemed impossible to answer, because so few bones have been found. This is where new genetic techniques have changed everything.

Reading Skeletons Through DNA

David Gokhman and his colleagues at the Weizmann Institute of Science in Israel developed a groundbreaking way to extract physical clues about Denisovans from their DNA. Instead of just reading the genetic sequence, they looked at how Denisovan genes were regulated—tiny chemical switches that control when and where genes are active.

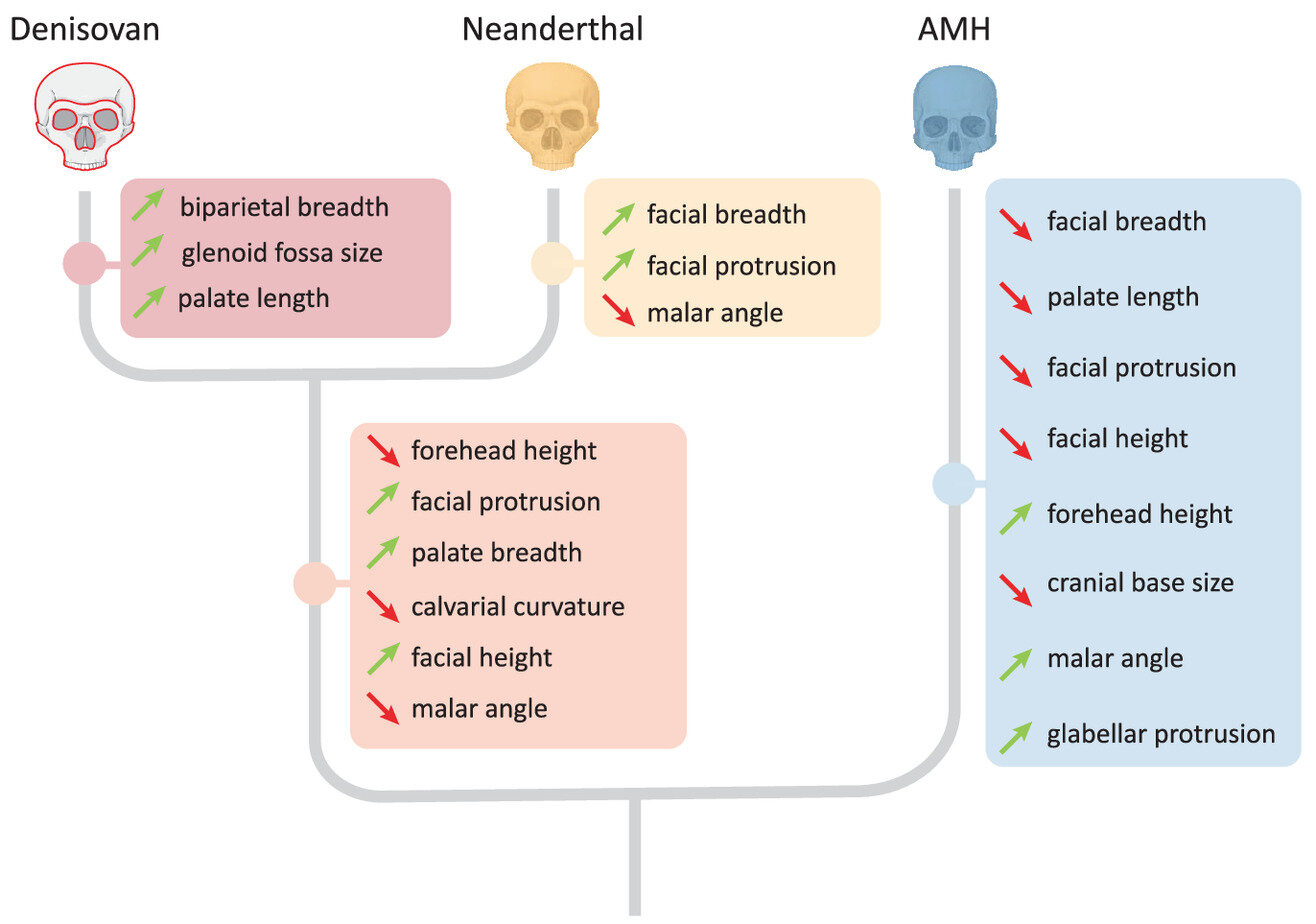

Why is this important? Because these subtle genetic changes can shape physical traits, like the width of the skull or the slope of the forehead. By studying these patterns, the researchers could reconstruct a genetic “blueprint” of Denisovan anatomy.

The results were astonishing. The team identified 32 key traits, most related to skull shape. This profile gave them a powerful new tool: a way to scan the fossil record for skulls that might belong to Denisovans.

Testing the Blueprint

Before applying the technique to unknown fossils, the scientists tested its reliability. They used the same approach to predict physical traits of Neanderthals and chimpanzees—species we already know well from fossil evidence. The predictions matched reality with over 85% accuracy.

Confident in their method, they turned to fossils from the Middle Pleistocene, a period when multiple human lineages roamed the Earth. They measured traits like forehead height and head width on ten ancient skulls, comparing them to the Denisovan genetic blueprint. Each skull received a score showing how closely it matched the predicted Denisovan features.

Two skulls stood out: the Harbin skull and the Dali skull, both from China. The Harbin skull matched 16 of the Denisovan traits, while the Dali skull matched 15. These skulls, massive and strikingly different from modern humans, may well be the long-sought faces of the Denisovans.

A Possible Ancestor

The study also revealed something even more intriguing. A third skull, known as Kabwe 1 from Zambia, showed strong links to both Denisovans and Neanderthals. This suggests it could represent an ancestral population, a group that lived before Denisovans split away from Neanderthals as a separate lineage. If so, Kabwe 1 might be the missing link that helps us trace the origins of this mysterious branch of humanity.

The Broader Implications

The significance of this research extends far beyond Denisovans themselves. It demonstrates that DNA can reveal physical traits of species we may never find complete skeletons for. This technique could help identify other extinct human relatives hidden in the fossil record, refining our understanding of human evolution.

As Gokhman and his colleagues wrote, “Our work lays the foundation for future efforts to infer phenotypes of other extinct hominin groups and to refine the taxonomic classification of the fossil record using genetic data.” In other words, the fossil record is no longer silent—we now have the tools to make its fragments speak.

A Human Story That Keeps Expanding

The Denisovans remind us that our past is not a straight line, but a tangled web of relatives, encounters, and exchanges. They are not simply “others” who vanished—they are part of us, living on in our DNA, shaping our biology, and expanding our understanding of what it means to be human.

The fact that we discovered them only through genetics speaks to the wonder of science. In a tiny piece of bone, hidden in a Siberian cave for tens of thousands of years, lay a secret that rewrote our history. Now, with every new technique and every new discovery, we peel back more layers of that story.

The Denisovans are no longer shadows. They are emerging from the mists of time, their faces reconstructed not by chisels or paintbrushes, but by the code of life itself. And their story is still being written.

More information: Nadav Mishol et al, Candidate Denisovan fossils identified through gene regulatory phenotyping, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2513968122