Imagine waking up one morning to find that the global trade network has collapsed—ships idle in harbors, planes grounded, trucks out of fuel. A nuclear war, a colossal solar flare, or a raging pandemic could bring international commerce to a screeching halt. No more imported wheat, bananas, or fuel. In such a chilling scenario, how would cities feed themselves? Could gardens on rooftops and vacant lots really keep millions from starving?

A groundbreaking new study published in PLOS One by Dr. Matt Boyd of Adapt Research Ltd and Professor Nick Wilson from the University of Otago dives into this very question. Focusing on the real-world example of Palmerston North—a median-sized city in New Zealand—the researchers have developed a sobering but essential analysis of how cities might sustain themselves when the world as we know it grinds to a halt.

The Limits of Urban Agriculture: Hope and Hard Truths

Urban agriculture has often been touted as a solution for everything from climate change to food deserts. The image of city dwellers harvesting tomatoes on rooftops and tending community gardens in vacant lots is certainly compelling. But Boyd and Wilson’s findings cast a stark light on the limitations of this vision when it comes to surviving an abrupt global catastrophe.

Their analysis, based on satellite imagery and land-use calculations, found that even if all available urban spaces in Palmerston North were maximally used for agriculture—home gardens, parks, rooftops, and more—the resulting food could only support about 20% of the city’s population. That’s a far cry from the self-sufficiency cities would need if cut off from global supply chains.

The conclusion? Urban agriculture alone is not enough. But hope is far from lost.

Near-Urban Farmland: The Unsung Hero of Resilience

Where urban agriculture falls short, near-urban land could step in to fill the gap. By extending food production just beyond city boundaries, Boyd and Wilson suggest that it would be possible to feed the entire population of Palmerston North, provided around 1,140 hectares (roughly 11.4 square kilometers) of land is dedicated to farming.

This land wouldn’t need to be pristine farmland. Marginal, currently unused land, or even land used for low-priority purposes could be repurposed in an emergency. The proximity is key: short travel distances would reduce the need for transportation fuel, which would be in short supply.

In fact, the researchers recommend allocating an additional 110 hectares of land solely for biofuel production. This biofuel could keep essential agricultural machinery running even in the absence of oil imports, making the entire local food system more self-sustaining.

Best Crops for Survival: Peas, Potatoes, and Plan B

So, what crops should we grow when the stakes are survival itself?

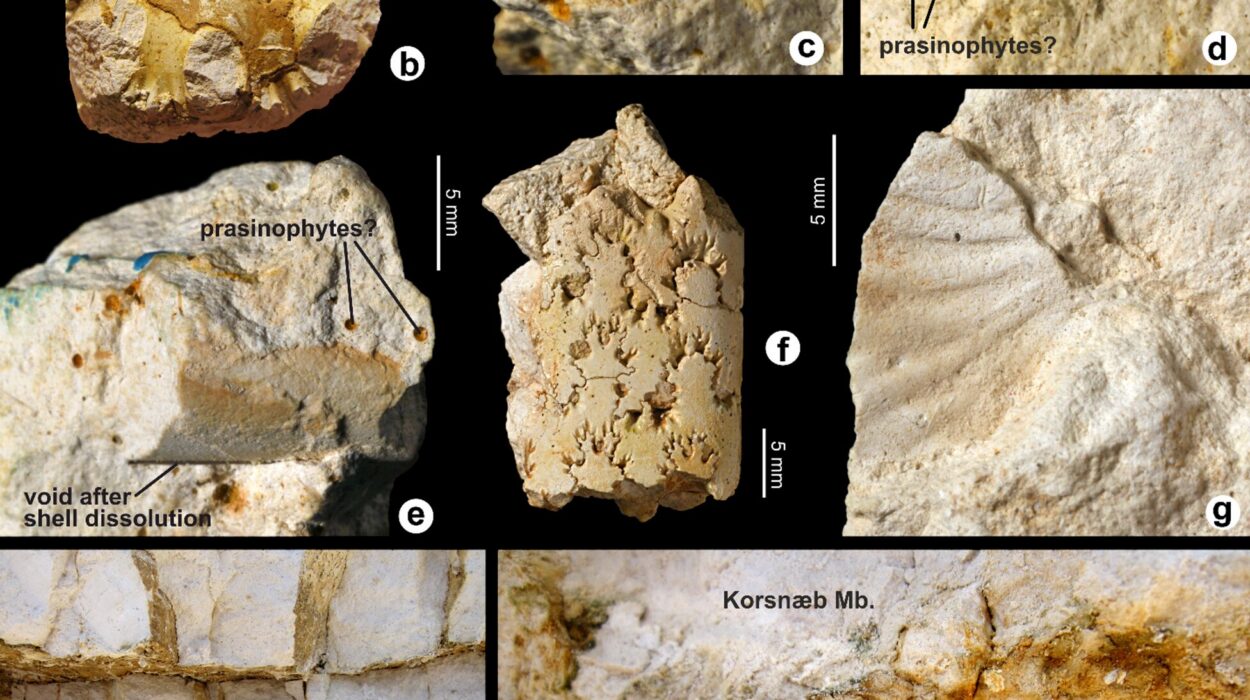

In scenarios with a stable climate, the study identifies peas as the top performer for urban farming. Why peas? They’re rich in protein and calories, have a compact growing footprint, and can be cultivated in small spaces. Near-urban farmland in normal climates, on the other hand, is best used for potatoes—a reliable, calorie-dense staple that thrives in temperate conditions.

But the study also dives into darker scenarios, like nuclear winter—a chilling prospect in both metaphor and reality. In the aftermath of widespread nuclear war, soot and ash in the atmosphere could block sunlight and cool the planet significantly. Under these conditions, researchers found that sugar beets and spinach fare best in urban settings, while wheat and carrots become optimal choices for nearby farmland.

These are not just academic observations. They offer a concrete survival guide—one that could inform national preparedness strategies and local government policies.

Infrastructure, Seeds, and Strategy: The Other Ingredients

Growing food is only part of the equation. Boyd and Wilson emphasize that a truly resilient urban food system must also account for infrastructure and logistics.

Food processing facilities would need to be built or repurposed locally. Seeds would need to be stored and distributed efficiently. Equipment would have to be maintained, and water supplies secured. All of this requires coordination, investment, and planning—not in the panic of an unfolding crisis, but in the calm before the storm.

Moreover, the study suggests integrating food resilience into national security policy. Just as governments maintain military defenses and emergency services, so too should they consider food sovereignty a matter of national survival.

“Success depends on integrating food production into urban areas, protecting and making ready near-urban land, building local food processing infrastructure, ensuring seed availability, and integrating food into our national security policy framework,” says Dr. Boyd.

From Theory to Action: Lessons for Cities Worldwide

Although the study focuses on Palmerston North, its implications are global. The city was chosen for its median size and temperate climate—making it a reasonable stand-in for many other urban centers across the developed world.

The methods Boyd and Wilson used—especially the Google Earth-based land assessments and crop yield modeling—can be applied anywhere. Every city, from Boston to Berlin, from Tokyo to Toronto, has the capacity to evaluate its food security based on similar criteria.

It’s a call to action for urban planners, mayors, and national leaders. Waiting until disaster strikes would be a mistake. Resilient food systems must be built now, with an eye toward the most dire of possibilities. And even if those catastrophic scenarios never unfold, the benefits—local food, reduced emissions, greener cities—would still be well worth the investment.

The Bigger Picture: Beyond Apocalypse

While the specter of global catastrophe makes for urgent headlines, this research is also deeply relevant to ongoing challenges like climate change, fossil fuel dependency, and urban overpopulation.

As global supply chains become increasingly fragile and climate extremes threaten agricultural output, localized food systems offer a pathway to resilience and sustainability. Urban agriculture, combined with strategic near-urban farming, represents not just a crisis response strategy, but a reimagining of how cities function in a changing world.

It’s a vision that blends innovation with pragmatism—rooftop greenhouses, hydroponic containers, vertical farms, and biodiesel tractors humming on the outskirts of the city. It’s a world where our survival doesn’t depend on distant ports and ships, but on the soil beneath our feet and the communities we cultivate around it.

Final Thoughts: Cultivating Resilience in an Uncertain Future

The study by Boyd and Wilson is more than a warning—it’s a roadmap. It doesn’t simply ask “what if the worst happens?” but dares to answer it with data, ingenuity, and a call to preparedness.

In a time when headlines are dominated by conflict, climate disasters, and global instability, the idea of growing our own food might feel like a return to basics. And perhaps that’s the point. In complexity, there is fragility. In simplicity, there is strength.

If cities can begin now—mapping their near-urban land, stockpiling seeds, building community gardens and food processing hubs—they can be ready. Ready not just to survive the unimaginable, but to thrive in its aftermath.

And maybe, just maybe, that preparation will become a catalyst for a better, more sustainable world—crisis or not.

Reference: Boyd M, et al. Resilience to abrupt global catastrophic risks disrupting trade: Combining urban and near-urban agriculture in a quantified case study of a globally median-sized city, PLOS One (2025). DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0321203