When we imagine nature’s battlefields, we often think of lions clashing on the savannah or stags locking antlers in the forest. But sometimes the fiercest contests take place in places too small for the human eye to notice. Deep in the soil, crawling among the roots of onions and garlic, lives a creature less than half a millimeter long—the bulb mite. Despite its size, this tiny animal embodies the raw, unforgiving essence of evolution: a world where survival and reproduction come at any cost.

For the bulb mite (Rhizoglyphus echinopus), mating isn’t just about charm or subtlety. It is about violence. In fact, males often fight to the death, and sometimes, the victor eats his rival. These shocking battles, reminiscent of alien gladiatorial arenas, show just how brutal and ingenious nature can be when it comes to passing on genes.

Fighters in the Soil

Researchers at Flinders University have been studying the bizarre mating behaviors of bulb mites, uncovering a story of survival that blends both cooperation and cruelty. These mites, which can reproduce so quickly that they become agricultural pests, have developed a unique strategy for ensuring that the “fittest” males father the next generation.

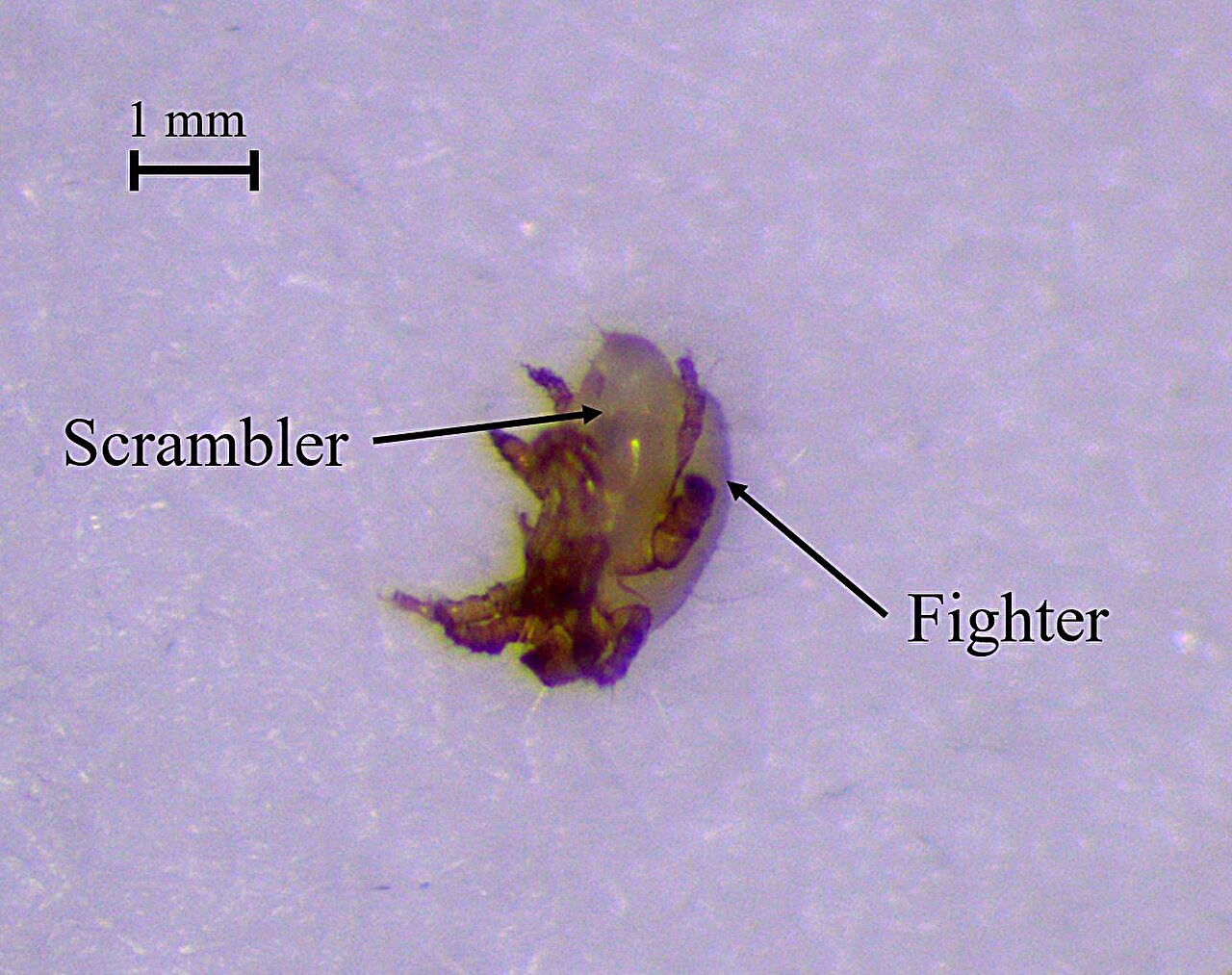

Some males are born “fighters.” They develop thickened, dagger-like legs, which they use to attack rivals. Other males are “sneakers,” smaller and less aggressive, who attempt to mate with females while the fighters are distracted. But when fighters meet, things can turn deadly.

The new study, published in the journal Evolution, revealed that these mites are not mindless killing machines. They can actually regulate their aggression, adjusting how violently they attack based on whether their opponent is family or a stranger.

Blood Ties and Deadly Choices

In many animals, kinship influences behavior. Lions tolerate their brothers when forming coalitions. Vampire bats share food with relatives. Even in human societies, kinship has shaped cooperation and conflict for millennia. But in the world of insects and arachnids, this isn’t always the case. For example, species like Colorado potato beetles and praying mantises show no such restraint—siblings are just as likely to fight as strangers.

Bulb mites, however, are different. The researchers found that males were significantly less aggressive toward their brothers. While they still competed, fights among kin were less likely to end in death. Against unrelated males, though, fighters showed no mercy. If females were nearby, the violence escalated. Rivals were attacked, killed, and sometimes even eaten—cannibalism serving as both a brutal elimination tactic and a way to gain energy for future battles.

This kin-sensitive aggression highlights a sophisticated evolutionary strategy. By sparing brothers, fighters avoid weakening their own genetic legacy. After all, if a sibling fathers offspring, those offspring still carry shared genes. Killing an unrelated rival, on the other hand, ensures that only the victor’s bloodline survives.

The Evolutionary Logic of Violence

At first glance, this behavior might seem cruel, even wasteful. Why kill and eat members of your own species, when the goal is reproduction? But from the perspective of evolution, it makes sense. Every species is shaped by the struggle to pass on genes, and behaviors that increase reproductive success—no matter how violent or shocking—can be favored by natural selection.

Dr. Bruno Buzatto, senior author of the study, explains that understanding such dynamics isn’t just academic curiosity. Male competition influences long-term population growth, which means aggression levels in a species can directly affect how pests spread—or how endangered species decline. In the case of bulb mites, learning how aggression and kinship interact could one day help us manage their populations and protect vital crops like onions and garlic.

A World of Tiny Warriors

What makes this discovery especially fascinating is how it reshapes our view of life at the microscopic scale. To the naked eye, bulb mites are specks of dust. But under a microscope, they are warriors locked in battles as dramatic as any seen in lions, wolves, or humans. They fight with specialized weapons, discriminate between kin and strangers, and adjust their tactics depending on the presence of females.

It reminds us that nature’s dramas are not confined to the grand and visible. The same evolutionary forces that drive elephants to spar and birds to sing also sculpt the behaviors of creatures invisible to us. Even at half a millimeter long, bulb mites are caught in the same timeless struggle: to win, to reproduce, to survive.

Lessons from a Ruthless World

The story of the bulb mite may seem alien, even grotesque, but it echoes something universal. Life is never just about survival—it is about competition, cooperation, and the fine balance between them. In these mites, we see the razor’s edge of evolution, where mercy exists only within the bonds of kinship, and victory sometimes requires violence.

It is a reminder that the rules of nature are not always gentle. They are shaped by what works, not what feels fair. And yet, within that brutality, there is also a strange beauty: the intricate strategies, the hidden choices, the constant dance between bloodline and survival.

So next time you chop an onion or crush garlic, remember—beneath the soil, too small for your eyes to see, tiny warriors are fighting battles older than humanity itself. Their story is one of life’s rawest truths: that even in the smallest corners of the world, the struggle to pass on genes can give rise to both savagery and strategy.

More information: Incheol Shin et al, Mate competition and relatedness among males mediate the evolution of lethal fights in bulb mites, Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1093/evolut/qpaf094