Deep in the mist-covered forests of Bwindi Impenetrable National Park in Uganda, scientists have uncovered an extraordinary secret about one of our closest relatives—the mountain gorilla. New research from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology and the University of Turku reveals that some female mountain gorillas, like humans and a few whale species, can live for many years after giving birth to their last offspring.

For decades, scientists have believed that most animals reproduce throughout their adult lives until death. But this new study, drawing on more than thirty years of meticulous data, challenges that assumption. Nearly one-third of the adult female mountain gorillas observed stopped reproducing yet survived for a decade or longer afterward. In essence, these remarkable primates spend at least a quarter of their adult lives in what researchers call a “post-reproductive phase.”

This finding, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, adds an exciting new piece to the evolutionary puzzle of human aging and menopause. It suggests that the roots of living long after reproduction may stretch far deeper into our shared primate history than previously imagined.

Life After Motherhood

The study’s senior author, Martha Robbins, who has directed the long-term Bwindi mountain gorilla research project since the late 1990s, describes the inspiration behind the study: “We wanted to formally test the presence of long post-reproductive lifespan in mountain gorillas, as we had observed old females that had ceased reproduction for a long time, yet still appeared in very good health.”

Her observations weren’t just anecdotal. Robbins and her team had been tracking individual gorillas for over three decades. Two females that were already adults when the study began in 1998 are still alive today—but they had their last babies back in 2010. These matriarchs, now well into their 40s, continue to live peacefully within their groups, nurturing relationships and maintaining social bonds despite no longer reproducing.

For a species whose average lifespan rarely exceeds 50 years, a post-reproductive span of over ten years is astonishing. It means that these females are spending around a quarter of their adult lives after their reproductive years are behind them—something that, until now, was thought to be nearly exclusive to humans and certain whale species like orcas and pilot whales.

The Evolutionary Puzzle of Post-Reproductive Life

From an evolutionary standpoint, living long after reproduction ends poses a question that has fascinated and puzzled scientists for generations: if evolution favors traits that help pass on genes, why would natural selection allow a female to survive long after she can no longer have offspring?

In most animal species, life and reproduction are tightly intertwined. A female’s biological purpose, in evolutionary terms, is to produce and raise offspring. Once reproduction ceases, survival becomes biologically unnecessary—unless there’s another advantage.

For humans, this post-reproductive life stage—menopause—has long been linked to the “grandmother hypothesis.” This theory suggests that older women enhance the survival chances of their grandchildren by helping to care for them, pass down knowledge, and contribute to the group’s wellbeing. Their experience and social support may have indirectly improved the reproductive success of their kin, making longevity after reproduction evolutionarily beneficial.

Could a similar pattern exist in gorillas?

Clues Hidden in the Mist

The study’s lead author, Nikos Smit, a postdoctoral researcher at both institutions, emphasizes that while the findings are clear, the reasons behind them are still not fully understood. “The evolutionary pressures which might have favored the evolution of post-reproductive lifespan, or even menopause, in gorillas remain unclear—we are still far from deciphering the evolutionary roots of these traits in gorillas and beyond,” he explains.

To uncover those roots, scientists have spent years observing the social and biological lives of these gorillas. Female mountain gorillas form close-knit social groups, often led by a dominant silverback male. They share grooming, social play, and even conflict resolution. Older females, though no longer reproducing, often remain central to these groups.

Their presence provides stability. Younger females may learn from them, juveniles play around them, and the silverback’s attention and trust toward them can help maintain harmony within the troop. This social importance might offer one possible explanation for why natural selection didn’t simply “discard” females after their reproductive years. Their wisdom and social roles could still benefit the group’s survival.

The Mystery of Menopause in the Wild

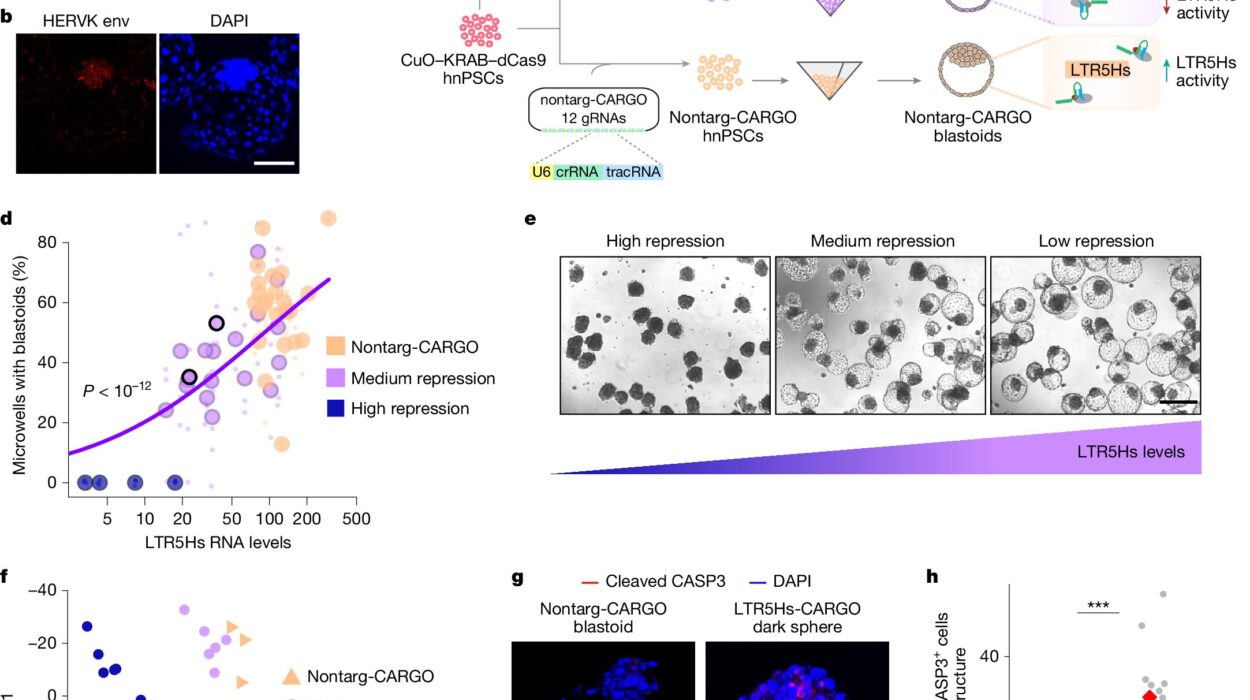

One of the most intriguing aspects of the study is what it suggests about menopause itself. In humans, menopause is defined as the permanent cessation of menstruation due to loss of ovarian function, usually occurring around midlife. But in the wild, confirming menopause in animals is far more complex.

It requires not just long-term behavioral data but also physiological and hormonal measurements—something extremely difficult to obtain in free-ranging populations. Still, the evidence from this study points strongly toward the existence of menopause-like changes in gorillas.

The researchers noted long periods without reproduction, minimal mating behavior, and evidence from previous hormonal studies that older female gorillas experience changes similar to those seen in menopausal women. While definitive proof awaits more detailed endocrine analysis, the signs are compelling: mountain gorillas may indeed undergo a form of menopause.

A Shared Legacy with Humans

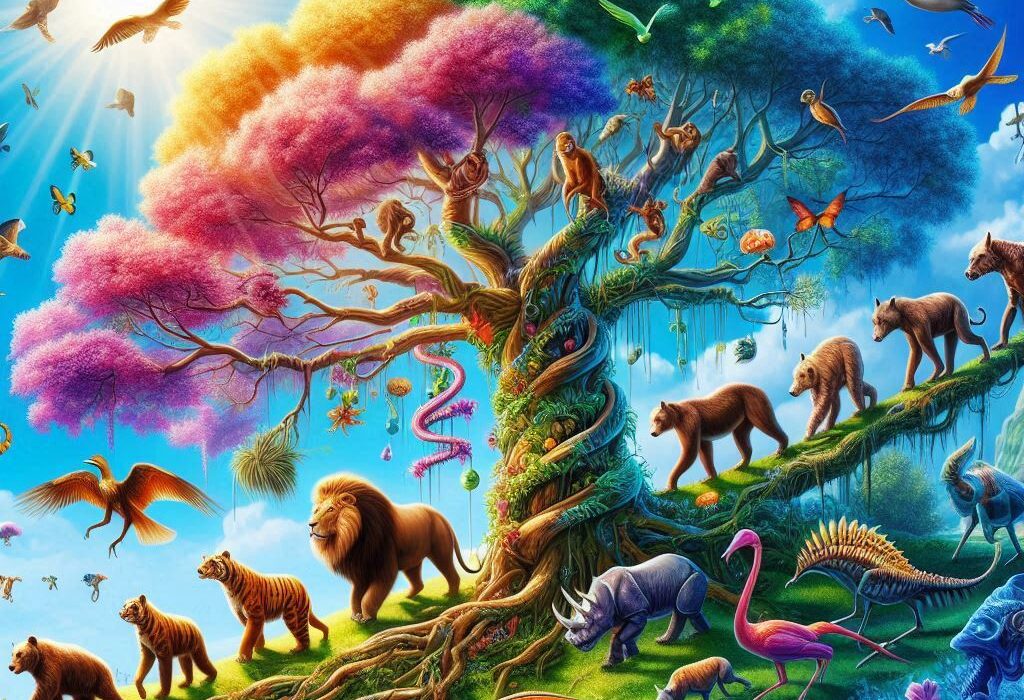

If confirmed, this discovery could reshape our understanding of primate evolution—and our own place within it. Until recently, only humans, a few whale species, and one small population of chimpanzees were known to experience extended post-reproductive life. The addition of mountain gorillas to that list suggests that this trait might not be as rare as once believed.

More importantly, it hints that the biological and social mechanisms behind long post-reproductive life might have existed in our common ancestors with these great apes. In other words, the roots of menopause and the value of elder females could reach back millions of years into the evolutionary history of African hominids.

This discovery paints a more interconnected picture of life’s evolution—one in which the wisdom of age, the strength of community, and the bonds between generations play a vital role in survival.

The Value of Longevity

The concept of “living long after life’s work is done” takes on profound meaning in this context. The older female gorillas, though no longer mothers, continue to contribute to their social groups in subtle but powerful ways. Their experience may help younger females raise infants, their calm presence may reduce aggression within the group, and their deep familiarity with territory and resources may benefit everyone.

Just as grandmothers in human societies often serve as anchors of wisdom, memory, and care, elder gorillas might embody a similar evolutionary role—a living bridge between generations. The long post-reproductive lifespan may not just be an evolutionary accident, but an adaptation that enhances the collective wellbeing of a social species.

What This Means for Us

In a world where aging is often viewed as decline, the story of the mountain gorilla offers a refreshing perspective. It suggests that longevity and aging are not merely biological leftovers but meaningful parts of life’s design.

For humans, the ability to live long after reproduction has shaped our societies, our cultures, and our families. It has allowed knowledge, skills, and compassion to flow across generations. The discovery that gorillas might share this trait reminds us that the essence of care and connection transcends species boundaries.

It is a reminder that evolution does not only favor the strong or the fertile—it also values the wise, the nurturing, and the enduring.

The Continuing Mystery

Much remains to be uncovered. Researchers continue to gather data, hoping to analyze hormone samples that could confirm whether menopause truly occurs in these gorillas. But even without complete proof, this finding has already expanded our understanding of what it means to live, to age, and to belong within a social world.

The forests of Bwindi still hold many secrets, whispered in the rustle of leaves and the soft grunts of the gorillas that call it home. And among them, the quiet strength of an old female—her silver-streaked fur glinting in the light filtering through the canopy—tells a story older than humanity itself: that life’s value is not defined by reproduction alone, but by the enduring bonds and wisdom that life leaves behind.

More information: Nikolaos Smit et al, Post-reproductive lifespan in wild mountain gorillas, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2510998122