In a world spinning faster than ever, with technology accelerating our days and stress pressing heavily on our shoulders, a curious thing often brings peace: the soft purring of a cat, the exuberant bark of a dog, the serene silence of a fish tank bubbling in a corner, or even the gentle flutter of a parrot’s wings. Pets. For all their simplicity, pets are among the most powerful companions humans can have—not just emotionally, but physiologically and psychologically.

Their presence transcends the obvious. They are not merely animals who share our homes; they become threads woven into the fabric of our emotional lives. Pets influence our habits, our routines, and, as modern science increasingly shows, the very structure of our minds and bodies.

A Love Rooted in Evolution

The bond between humans and animals is no modern invention. Archaeological records show that as far back as 14,000 years ago, humans were buried with dogs, suggesting a spiritual or familial connection. Cats were worshipped in ancient Egypt, and horses transformed warfare, agriculture, and travel. But beyond utility and myth, a quieter revolution was taking place: animals were becoming our emotional mirrors.

This ancient companionship didn’t evolve by accident. Humans, as social beings, have an inherent need for connection. When that connection is extended to animals—especially domesticated ones—it taps into deep evolutionary responses. Oxytocin, the “bonding hormone” released when humans gaze into each other’s eyes or embrace, is also released when we interact with our pets. This creates a feedback loop of affection and trust, helping to lower stress and increase well-being.

In this subtle biochemical symphony, a cat curling into your lap or a dog placing its paw on your knee becomes more than a gesture—it becomes medicine.

The Mental Health Revolution in Fur and Feathers

Modern psychology has long acknowledged the importance of connection in managing mental health. But only in recent decades has the scientific community begun to fully understand how profoundly pets contribute to our psychological well-being.

Pets offer unconditional love. In a world where acceptance often feels conditional—based on performance, appearance, or social standing—a pet’s affection is pure and unchanging. This creates a stabilizing emotional anchor, especially for individuals facing loneliness, depression, or anxiety.

Studies have shown that pet owners experience lower rates of clinical depression compared to non-pet owners. People living with chronic mental health conditions report fewer symptoms when they live with a pet. The mechanisms behind this are multifaceted: emotional support, increased physical activity, structured routines, and tactile stimulation all play a role.

For example, stroking a dog or cat for just a few minutes can reduce cortisol levels—the primary stress hormone—and increase serotonin and dopamine, which promote a sense of calm and happiness. The rhythmic sensation of fur under your fingers or the deep rumble of a cat’s purr acts almost like a natural sedative, easing the turmoil within.

Pets and the Loneliness Epidemic

Loneliness is not merely a social inconvenience—it is a public health crisis. Research from major health organizations, including the U.S. Surgeon General, now recognizes social isolation as a risk factor comparable to smoking or obesity in terms of long-term health outcomes.

This is where pets quietly perform a heroic role. For the elderly, especially those living alone or in long-term care facilities, pets often become lifelines. A dog nudging its owner for a morning walk or a cat rubbing its face against their hand gives structure to the day and reminds them they are needed. That sense of being needed, of being responsible for another life, stirs the spirit and sustains hope.

Moreover, pets serve as social catalysts. A dog at the end of a leash opens the door to conversations in parks or on sidewalks. Animal lovers tend to connect, forming communities where once there was isolation. For those who have difficulty with human relationships—such as individuals with autism spectrum disorder or social anxiety—pets can be gateways to trust and emotional expression.

Children and Animals: A Deep Developmental Dance

The bond between children and animals is something magical, yet it is also profoundly biological. A child confiding in their hamster or reading aloud to a Labrador isn’t just being cute—they are learning to trust, communicate, and care.

Children who grow up with pets often exhibit higher self-esteem, improved social skills, and lower levels of anxiety. Interactions with animals encourage the development of empathy, responsibility, and emotional regulation. For neurodivergent children, particularly those with autism, pets provide a non-judgmental presence that makes emotional connection more accessible.

Therapy animals, particularly dogs and horses, have been used effectively in behavioral and developmental therapy for children. Equine-assisted therapy, for instance, has shown significant benefits for kids with ADHD, trauma histories, or emotional dysregulation. There’s something uniquely grounding in the steady rhythm of a horse’s gait or the silent trust of a large animal allowing a child to sit astride its back.

Physical Health: Fur and Heartbeats

Beyond the psychological benefits, the impact of pets on physical health is equally remarkable. It begins with activity. Dog owners, for instance, are far more likely to meet recommended levels of daily exercise. Walking a dog isn’t just a chore—it becomes a lifestyle. Morning and evening walks integrate movement into the rhythm of life, lowering the risks of cardiovascular disease, obesity, and diabetes.

But exercise is only the beginning. Studies have shown that pet owners have lower blood pressure, reduced resting heart rates, and improved heart rate variability—key indicators of cardiac health. After major cardiac events like heart attacks, pet owners have higher survival rates than non-pet owners. The mere presence of a pet during recovery can accelerate healing, reduce hospital stays, and improve long-term outcomes.

Some researchers have even explored the “pet effect” on immune function. Children raised in homes with pets often have lower incidences of allergies and asthma, likely due to early exposure to diverse microbiomes. This “hygiene hypothesis” suggests that our immune systems develop resilience through early microbial exposure—something pets provide in abundance.

The Healing Power of Therapy Animals

As scientific understanding of the human-animal bond deepens, so does the integration of animals into therapeutic settings. Animal-Assisted Therapy (AAT) has become a recognized treatment modality in hospitals, nursing homes, schools, and rehabilitation centers.

Therapy dogs visit pediatric cancer wards, reducing the need for pain medication and providing moments of joy amidst fear. Horses help veterans with PTSD reconnect with trust and movement. Even rabbits and guinea pigs are being used in schools to help children manage anxiety.

One powerful example comes from hospice care. Therapy animals, particularly cats and dogs, have an uncanny ability to sense pain and emotional distress. In final days, when words are few and human contact grows tenuous, an animal curling up beside a patient can bridge the gap between life and death with quiet dignity and presence.

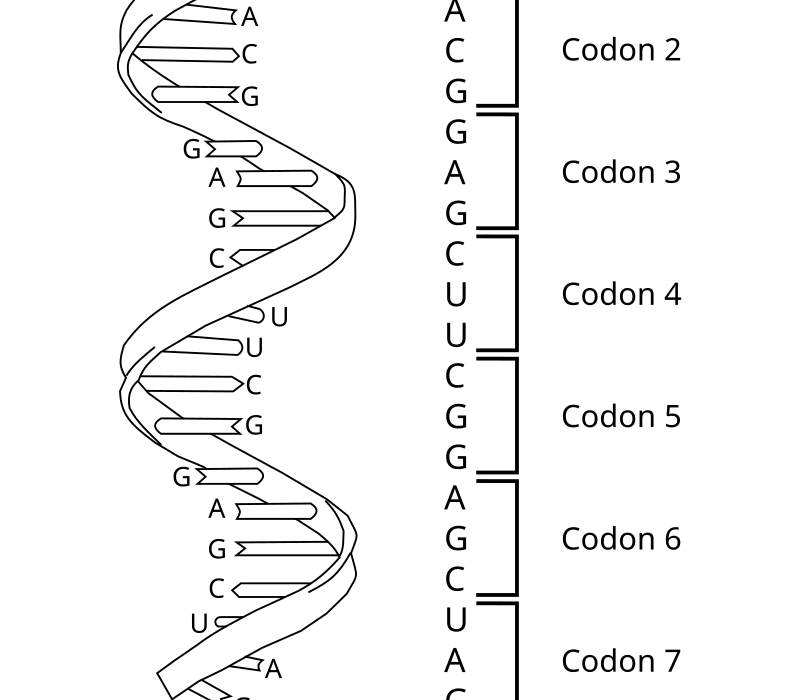

The Neurochemical Orchestra

What makes the human-animal bond so potent? The answer lies in a complex neurochemical cascade that begins the moment a pet enters the room.

Interaction with animals increases oxytocin—not just in humans, but in the animals themselves. This hormone plays a key role in bonding, trust, and emotional security. Simultaneously, levels of serotonin and dopamine rise, boosting mood and motivation. Cortisol, the hormone of stress, declines.

Neuroscience shows us that looking into a dog’s eyes activates the same reward centers in the brain that are triggered during parent-child bonding. It’s not just a metaphor: many pet owners describe their animals as “family,” and their brains seem to agree.

In some cases, pets may help regulate circadian rhythms. People with sleep disorders often sleep more soundly in the presence of their animals. The sense of safety and routine they bring helps anchor the body’s internal clock.

Grief, Loss, and the Pain of Goodbye

While much attention is given to the joys of pet ownership, we must also acknowledge the depth of pain that comes when a beloved animal dies. For many, the grief is as intense as losing a close human companion—and this should not be dismissed.

Psychologists now recognize “pet loss grief” as a legitimate form of bereavement. Mourning a pet involves not just the absence of their physical presence but the disruption of routines, the loss of emotional support, and the silence left in their wake.

And yet, even in their departure, pets offer a final gift. They teach us how to love without words, how to care with devotion, and how to let go when the time comes. In grieving them, we also honor the years they gave us—years filled with laughter, comfort, and unspoken understanding.

The Financial and Practical Challenges

Of course, pet ownership is not without its challenges. It requires time, money, energy, and emotional investment. Veterinary bills, food, grooming, and boarding all add up. Allergies, space constraints, and legal restrictions can complicate matters further.

Yet, when weighed against the documented physical and psychological benefits, the cost of pet ownership becomes not a burden but an investment. Just as we budget for health insurance or gym memberships, the emotional and physical return on the “cost” of pet care often proves substantial.

For those unable to own pets, alternatives exist. Volunteering at animal shelters, fostering, or even participating in animal-assisted therapy sessions can bring many of the same benefits. The key lies not in possession, but in presence—in shared moments of connection.

When the Pet is a Lifesaver

Some pets do more than offer companionship—they save lives. Service animals, particularly dogs, are trained to assist individuals with visual impairments, epilepsy, diabetes, and mobility issues. Seizure-alert dogs can detect subtle changes in behavior and chemistry, warning their owners minutes before a seizure occurs. Diabetic-alert dogs sniff out blood sugar fluctuations before symptoms appear.

For veterans and trauma survivors, psychiatric service dogs help manage flashbacks, interrupt harmful behaviors, and offer grounding during anxiety attacks. These aren’t just animals; they are medical partners with fur and eyes and loyalty that cannot be programmed.

Stories abound of pets who’ve alerted owners to house fires, guided them through panic attacks, or found them lost in the woods. Whether trained or intuitive, these animals transcend the label of “pet.” They become guardians.

The Science Still Unfolding

Despite the abundance of anecdotal and empirical evidence, the study of human-animal interactions is still a relatively young field. Researchers continue to explore not just if pets benefit health, but how and why. Are certain species more effective than others? Does breed matter? What role do personality, attachment style, and lifestyle play?

Preliminary studies suggest that the intensity of the bond, not the species, is what truly matters. Whether bird or lizard, rabbit or dog, it is the emotional connection and regular interaction that produces the strongest effects.

Advanced imaging techniques like fMRI and PET scans are beginning to show how animal interaction affects brain activity. The hope is that one day, pet companionship may be formally integrated into preventative and curative medical models, not as a novelty but as standard practice.

A Mirror to Our Better Selves

Ultimately, pets reflect who we are and who we hope to become. They reveal our capacity for kindness, patience, and vulnerability. They bear witness to our tears without judgment and celebrate our triumphs with tail wags and joyful leaps. They ground us in the present moment, a lesson so many mindfulness teachers struggle to impart.

In their eyes, we are never a failure. We are simply their person.

As the world grapples with rising mental health challenges, chronic illness, and disconnection, perhaps the simplest medicine lies at our feet or curled on our couch. Perhaps the purr of a cat or the wag of a tail is not just comforting—but essential.

And perhaps, in loving them, we remember how to love ourselves and each other—with loyalty, gentleness, and joy.