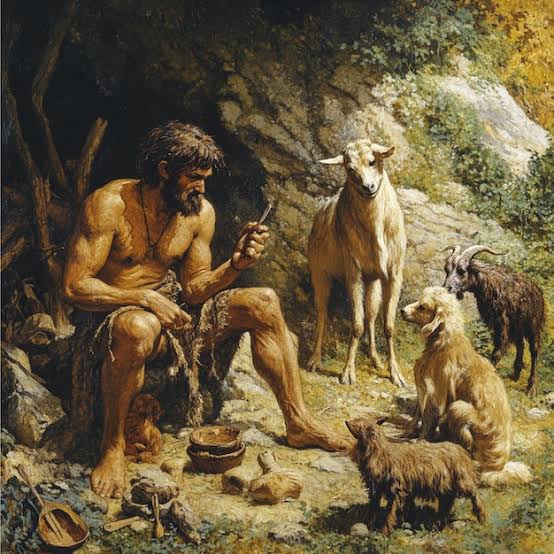

Long before the invention of writing, before the rise of cities or the plow, there was a moment—likely in the frigid twilight of the last Ice Age—when a human reached out to an animal, and the animal, instead of fleeing or fighting, stayed. In that silent exchange, something profound occurred. Two species, shaped by their own destinies, began to walk together. One would become the shepherd, the farmer, the breeder. The other, the companion, the servant, the friend.

The story of domestication is not merely a tale of utility or control. It is the intertwined biography of humans and animals—a coevolution of behaviors, brains, and bonds. This journey spans tens of thousands of years and stretches across every continent. It is written not only in fossils and DNA but in myth, art, and the shared memory of civilizations.

To understand domestication is to understand the essence of what it means to be human—not because we bent animals to our will, but because they, in turn, shaped us. The science of domestication is one of the most compelling chapters in the story of evolution, where nature and culture become inseparable.

Wolves at the Campfire: The Dawn of the Domestication Era

The domestication of the dog, Canis lupus familiaris, is the oldest known instance of animal domestication, and perhaps the most poetic. The earliest confirmed dog remains date back at least 14,000 years, but genetic evidence suggests that the split between dogs and wild wolves may have begun as far back as 30,000 to 40,000 years ago.

How did this begin? Most scientists now believe it was a process of self-domestication. Early humans left scraps near their camps. Bolder wolves, less fearful of human proximity, scavenged these remains. Over generations, those with more docile temperaments thrived near human settlements. In a kind of natural selection shaped by human presence, the ancestors of dogs were born.

Eventually, humans began to recognize the value of these canine neighbors. They offered protection, helped in hunting, and formed emotional attachments that transcended function. Archeological sites have revealed dogs buried beside humans, sometimes with grave goods, suggesting reverence and affection. These weren’t tools; they were partners.

What is remarkable is not only that dogs became domesticated, but that the process altered their brains and ours. Domesticated animals exhibit neoteny—the retention of juvenile traits. Dogs have shorter muzzles, floppier ears, and more playful behavior compared to wolves. These traits mirror childlike qualities, which may have triggered nurturing responses in humans. This dynamic began what some researchers call a “domestication syndrome,” a set of physical and behavioral changes that arise together when animals are selected for tameness.

The Genetic Dance: How Domestication Shapes Biology

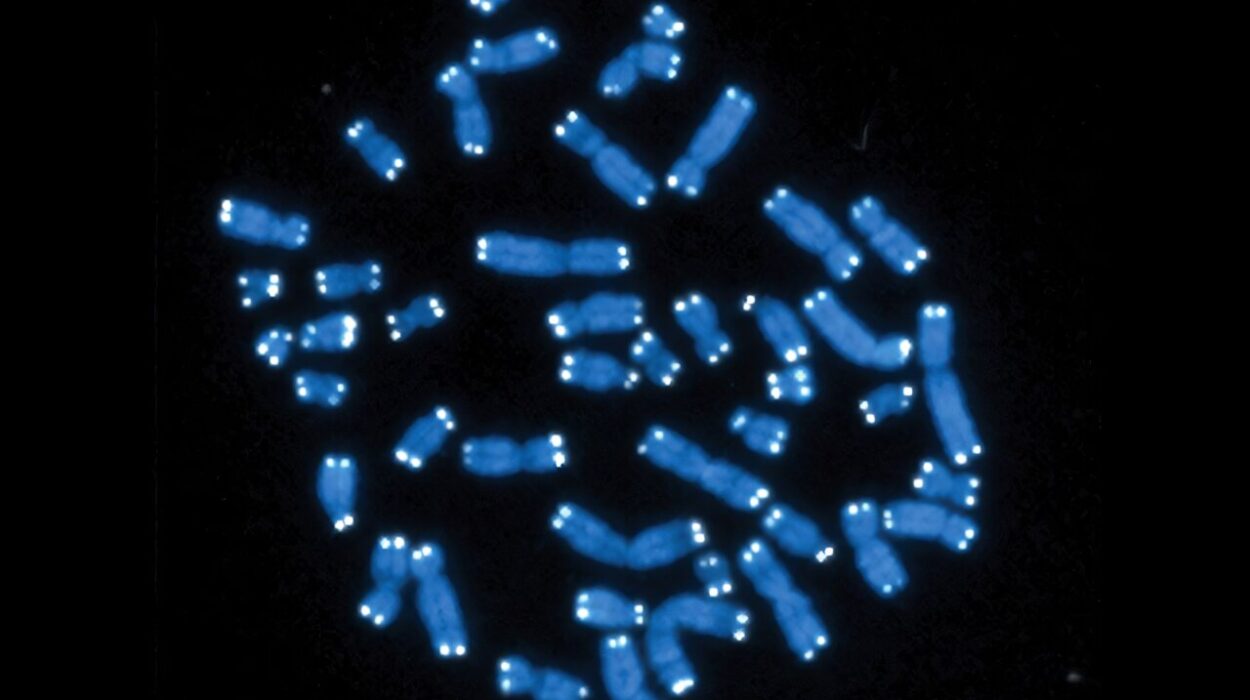

From a genetic perspective, domestication is an evolutionary experiment. It is not the same as taming. A tame animal is simply one that tolerates human contact. A domesticated animal has undergone genetic changes that make it fundamentally different from its wild ancestors.

These changes often center around the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis—the part of the brain involved in the stress response. Animals with reduced flight response to humans were more likely to survive in early domestication contexts. Over time, genes associated with stress, aggression, and reproductive behavior were subtly altered. These shifts had cascading effects.

In a famous experiment begun in 1959, Russian geneticist Dmitry Belyaev selectively bred silver foxes for tameness. Within just a few generations, the foxes began to exhibit dog-like traits: wagging tails, piebald coats, floppy ears, and increased sociability. The implications were profound. Selecting for behavior could trigger a suite of physical and developmental changes, revealing deep genetic connections between mind and body.

Modern genomics has further illuminated the domestication process. Specific genes have been identified that correlate with domesticated traits, such as the ASIP gene affecting coat color or the FOXP2 gene linked to communication abilities. But more importantly, it has shown that domestication often involved subtle tweaks rather than sweeping transformations—small adjustments in gene regulation rather than complete rewrites of genetic code.

Farming the Future: Domestication of Livestock

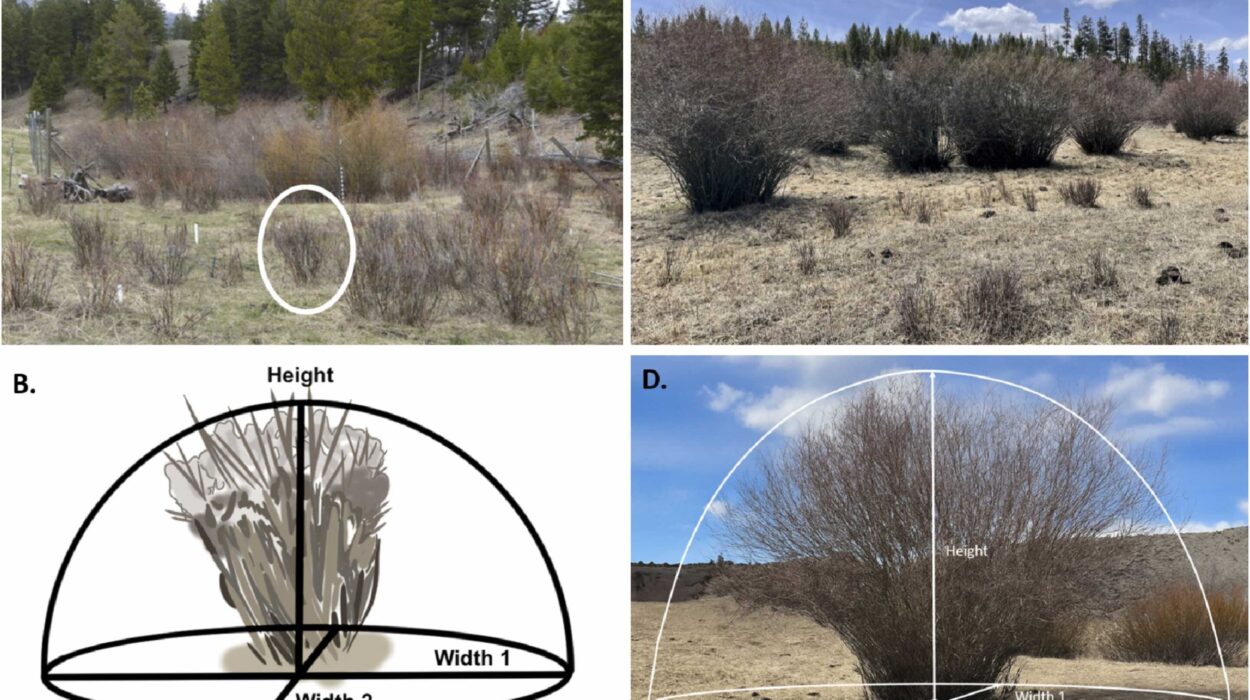

While dogs may have been companions, the domestication of livestock transformed human civilization. Between 10,000 and 8,000 years ago, as the Neolithic Revolution swept across the Fertile Crescent, humans began to domesticate animals for food, labor, and materials. Sheep, goats, pigs, and cattle were among the first.

The domestication of these species was complex and regionally varied. Goats and sheep were likely domesticated in the Zagros Mountains of modern-day Iran and Iraq, pigs in multiple locations across Eurasia, and cattle from wild aurochs in Anatolia and South Asia. Each involved selective breeding for docility, reproductive control, and traits like wool production, meat quality, or milk yield.

Unlike the dog, which self-domesticated through proximity, livestock were more deliberately managed. Humans penned them, selected mating pairs, and gradually altered their behaviors and bodies. Horn size diminished, skeletal structures changed, and cycles of reproduction were manipulated. Domesticated cattle became more docile and less alert, sacrificing survival instincts for utility.

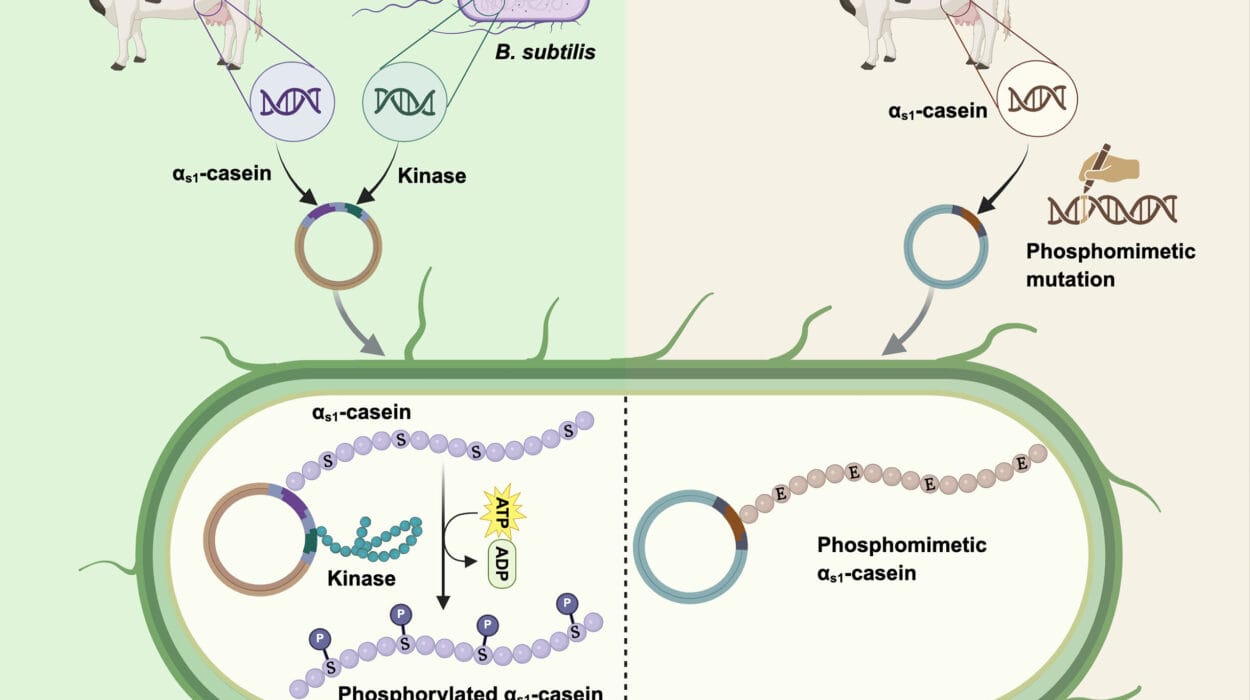

But these changes were not one-sided. Human societies also evolved. The shift to pastoralism required sedentary life, storage technologies, new tools, and social hierarchies. Milk, for example, created an evolutionary feedback loop. In populations where dairying became prevalent, natural selection favored adults who could digest lactose—a trait still absent in much of the world.

The Flightless Birds and Compliant Beasts: Domestication Expands

Domestication did not stop with mammals. Birds were next. Chickens, descended from the red junglefowl of Southeast Asia, were domesticated around 8,000 years ago. They were initially valued for cockfighting and ritual, only later becoming a staple protein source. Ducks and geese followed in various regions.

Horses represented another leap. Their domestication around 5,500 years ago in the Eurasian steppes revolutionized transportation, warfare, and trade. Horses gave rise to chariots, mounted armies, and the vast steppe empires that shaped history. Like dogs, horses bonded deeply with humans. Their eyes, like ours, are large and expressive. They read human emotions and learn complex tasks. Their domestication may have required not only biology but empathy.

Camels, reindeer, water buffalo, llamas, and alpacas were also domesticated, each transforming human societies in unique ecological niches. These animals were not simply biological resources. They became cultural cornerstones—sacred in rituals, painted on cave walls, and woven into oral traditions.

And yet, for all these successes, the list of domesticated animals remains small. Out of the thousands of wild vertebrate species, fewer than twenty have been successfully domesticated for food or labor. The reasons are instructive.

Why So Few? The Constraints of Domestication

The narrow roster of domesticated animals raises a haunting question: why not more?

Biologist Jared Diamond offered a compelling analysis in his book Guns, Germs, and Steel. He argued that successful domestication depends on a suite of characteristics: social structure, diet, growth rate, temperament, and breeding behavior. Animals that live in herds with hierarchical social systems are easier to domesticate because they can transfer that dominance to humans. Species that are picky eaters, grow slowly, or have aggressive temperaments are poor candidates.

Zebras, for instance, resist domestication despite their similarity to horses. They are skittish, aggressive, and prone to panic. Attempts to domesticate zebras have repeatedly failed. Elephants, while trainable, have never been truly domesticated. Their long gestation, late maturity, and complex emotions make them difficult to breed and manage in captivity.

Domestication, then, is not simply about human willpower. It is a convergence of biology, environment, and chance. Some species were pre-adapted to life with humans. Others were not.

Coevolution and the Human-Animal Bond

Domestication is not a one-way street. Just as animals changed under human influence, humans changed in response. The archaeological record shows shifts in diet, disease patterns, and even skeletal structure in early agricultural societies. But perhaps the most profound change occurred in the human brain.

The close bond with animals altered human psychology. Emotional empathy expanded. Communication skills evolved. In modern experiments, people show increased oxytocin levels—associated with bonding and trust—when interacting with pets. Domesticated animals have hijacked human social circuits, becoming part of our emotional ecology.

In return, domesticated animals evolved to “speak” our language. Dogs interpret human gestures better than chimpanzees. They respond to tone, posture, and facial expression. Some even learn hundreds of words. They have become, in a real sense, social partners.

This coevolution has ethical consequences. Domesticated animals are no longer merely part of the wild. They are part of the human world, subject to our care and our decisions. With this power comes responsibility—not just for their welfare, but for the ecosystems we’ve shaped around them.

Domestication in the Modern World: Industry and Identity

In the 20th and 21st centuries, domestication took on a new face. Industrial agriculture transformed animals into production units. Selective breeding intensified. Chickens that once grew in months now reached slaughter weight in weeks. Cows and pigs were bred for maximum meat, often at the cost of mobility and lifespan.

This mechanization alienated animals from human life. Fewer people raised livestock directly. The relationship that had once been built on partnership and proximity became abstracted through supply chains and supermarket aisles. Domesticated animals, once central to village life, became invisible laborers in a global machine.

Yet at the same time, the human-animal bond deepened in other ways. Companion animals flourished. Dogs and cats became family members. Urban societies, yearning for connection, turned back to animals for emotional support. Pet industries boomed. Animal-assisted therapy grew. In a strange twist, while farm animals were commodified, pets were elevated to emotional equals.

Scientific interest in domestication also surged. Genomics, archaeology, and ethology converged to explore the origins and effects of this ancient process. Domestication was no longer a quaint historical topic—it became a lens through which to understand human nature itself.

Looking Ahead: The Future of Domestication

Today, the frontier of domestication is expanding once again. Researchers have begun exploring the potential for new domestications, including species like the fox, the rabbit, and even wild rodents. Genetic engineering and CRISPR technology raise the possibility of accelerating or guiding domestication in unprecedented ways.

But this power also forces difficult questions. What does it mean to domesticate a species? At what point do we override its natural history? Are we creating animals that cannot survive without us? Are we engineering life purely for aesthetics, convenience, or profit?

In conservation circles, there is talk of “rewilding”—the opposite of domestication. It involves reintroducing species into ecosystems where they once roamed free. This approach acknowledges that domestication, while beneficial to humans, has often come at great ecological cost.

The future may also hold new kinds of relationships—between humans and artificially intelligent machines that mimic animals, or between humans and genetically modified organisms tailored for companionship or service. As the boundary between natural and artificial blurs, so too will the meaning of domestication.

The Great Collaboration

At its heart, domestication is a collaboration—a long, complex, imperfect dialogue between species. It is built not only on biology and environment, but on emotion, ritual, and time. It has enabled human civilization to flourish, fed billions, shaped ecosystems, and altered the evolutionary fate of many creatures.

But perhaps the most moving aspect of domestication is what it reveals about interdependence. We did not conquer the animal kingdom. We entered into an ancient agreement. The cow gives us milk, and we ensure her young survive. The dog guards our home, and we give him warmth. The horse carries our burdens, and we carry her lineage forward.

In every domesticated species, there is a trace of this pact—written not in words, but in gaze and gesture, in shared lives and mutual benefit.

And in that story, written over millennia, we see ourselves not as masters of the Earth, but as part of a great entangled web of life—one in which our fate has always been tied to those we chose to walk beside.