In the teeming coral reefs of the Indo-Pacific, where every corner brims with biodiversity, there lives a creature so extraordinary it borders on myth. It doesn’t breathe fire or grow to monstrous size. It doesn’t slither or sneak. It waits—hidden in burrows of sand and coral, beneath rocks, inside narrow holes like a trapdoor assassin. It is the mantis shrimp, and it wields the most powerful punch ever measured in the natural world.

It would be easy to overlook the mantis shrimp at first glance. Their sizes vary from two inches to over a foot long, and their flamboyant bodies shimmer with a kaleidoscope of iridescent colors—bright greens, shimmering blues, violent oranges, even neon pinks. But don’t let their beauty fool you. Behind those psychedelic eyes and ornate armor lies a predator equipped with biological weaponry so advanced it seems born from science fiction.

The mantis shrimp doesn’t roar or chase or ensnare. Instead, it ends conflicts in microseconds—by striking with such explosive speed and force that it can shatter aquarium glass, split open crab shells, and dismember its prey in a single, thunderous blow. Its weapon is not a claw or a tooth, but something else entirely—a biological hammer powered by physics and perfected by evolution.

The Secret Lives of Stomatopods

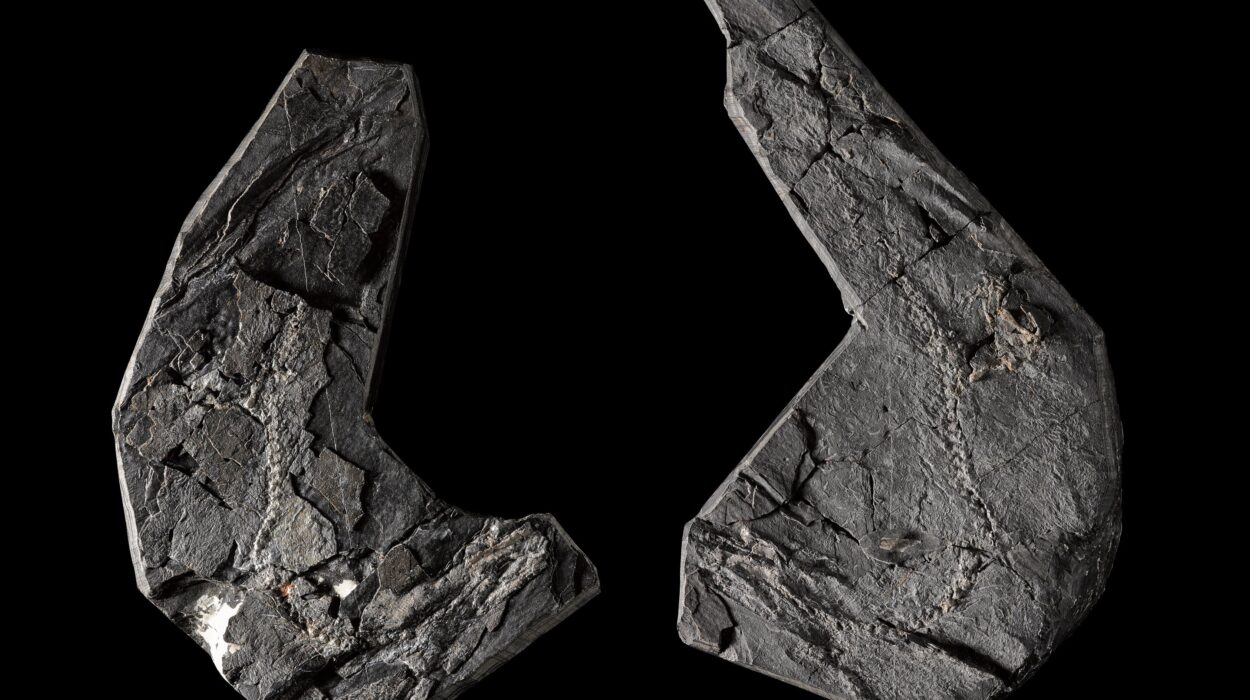

Though commonly called shrimp, mantis shrimp aren’t actually shrimp. They belong to a group of crustaceans known as stomatopods, which split from other crustaceans more than 400 million years ago. That makes them older than dinosaurs, older than flowering plants—ancient survivors of an evolutionary past most animals can’t trace.

There are over 400 known species of mantis shrimp, and they fall broadly into two hunting categories: the “spearers” and the “smashers.” Both are lethal, but in different ways.

Spearers have long, barbed appendages shaped like ancient javelins. They hide beneath the sand, waiting for fish or squid to pass overhead. Then, in a flash faster than the blink of a human eye, they launch their raptorial arms forward, impaling their prey with surgical precision.

Smashers, on the other hand, are armed with blunt clubs—calcified appendages that strike like sledgehammers. These are the gladiators of the reef. They take on snails, crabs, and even other mantis shrimp, and they don’t need to be stealthy. Their attack is brute force delivered with blistering speed.

It’s these smashers—particularly species like Odontodactylus scyllarus, the peacock mantis shrimp—that have captured the imagination of scientists and inspired awe in engineers. Their punch is not only the fastest in the animal kingdom—it may be the most violent acceleration of any body part in biology.

The Physics of a Punch That Defies Logic

To understand the power of the mantis shrimp’s punch, you have to leave behind ordinary scales of motion. Their club strikes with the acceleration of a bullet fired from a gun—reaching speeds of over 23 meters per second in less than 3 milliseconds. That’s roughly 50 times faster than a human blink. The force generated is equivalent to over 1,500 newtons. For an animal only a few inches long, that’s the equivalent of a human punching through concrete.

But what makes this even more astonishing is that the mantis shrimp doesn’t use muscle alone. Its power comes from a mechanism known as a “power amplification system”—a technique that allows biological systems to store energy and release it explosively, far beyond the limitations of muscle contraction.

Inside the mantis shrimp’s striking limb is a structure called a saddle-shaped spring made of a mineral called hydroxyapatite—the same material found in our bones. When the mantis shrimp flexes its muscles, it doesn’t strike immediately. Instead, it loads this spring, storing potential energy while locking the club in place using a latching system. When the latch releases, the stored energy unleashes all at once, flinging the club forward with devastating force.

It’s not unlike how a crossbow works: you draw the string slowly, store energy in the bent limbs, and then release it all at once for a quick, lethal shot. Nature, in this case, has engineered a weapon that exploits physics with incredible efficiency.

Cavitation: A Punch That Hits Twice

Perhaps the most mind-bending part of the mantis shrimp’s punch is that it doesn’t just rely on physical contact. It creates a second blow—made not of flesh and bone, but of bubbles and heat.

When the club strikes forward, it moves so quickly that it lowers the pressure in the surrounding water. This causes the water to literally boil—forming bubbles of vapor in a phenomenon known as cavitation. These bubbles collapse almost instantly with such violence that they create a shockwave, a burst of light, and heat that can reach temperatures comparable to the surface of the sun. This means the mantis shrimp lands not just one punch, but two—first from the physical strike, then from the implosion of cavitation bubbles.

In some cases, the prey is killed not by the direct hit, but by the shockwave that follows. To scale this up: imagine punching someone so fast that you boil the air between your fist and their face—and that boiling air then explodes.

Super Senses: The Eyes That See Beyond Human Imagination

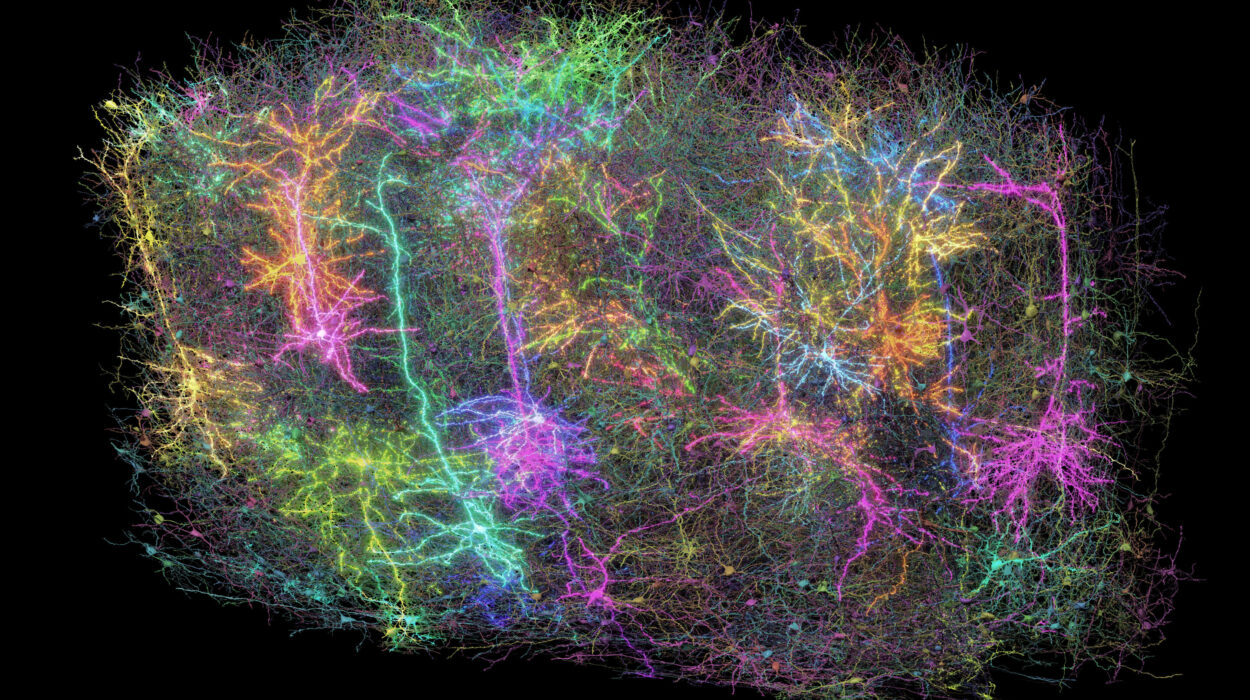

If the mantis shrimp were simply a powerhouse, it would already be remarkable. But its vision adds an entirely new layer of evolutionary sophistication. Their eyes—mounted on stalks and constantly in motion—are among the most complex in the animal kingdom. Each eye can move independently and has trinocular vision, meaning each eye can gauge depth on its own.

But more astonishingly, mantis shrimp can see polarized light and detect up to 16 types of photoreceptors—compared to just three in humans. This allows them to perceive ultraviolet, infrared, and polarized light patterns invisible to us. Some scientists speculate that this advanced vision helps them communicate with one another in hidden color codes, or to spot camouflaged prey on the reef floor.

Their visual processing system is so unique that neuroscientists study it for insights into new ways of computing and sensory processing. It’s not just seeing in more colors—it’s seeing in an entirely different language.

Armor Built for Destruction

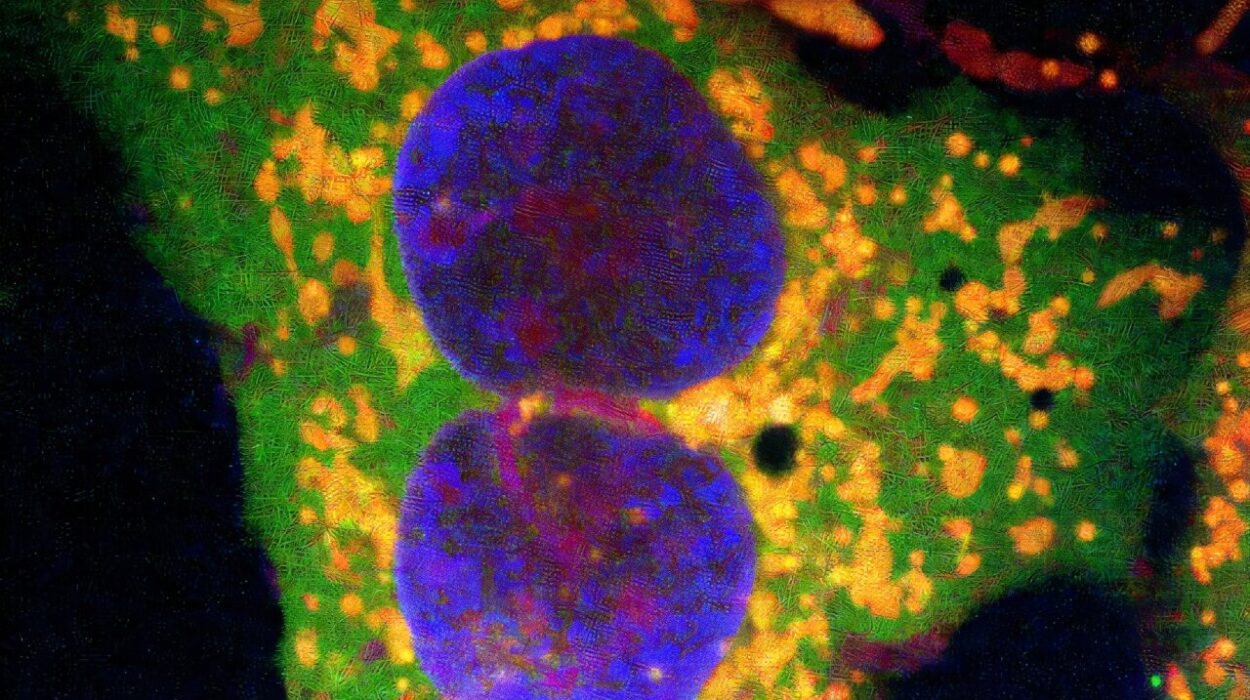

Of course, such devastating power would be useless if the shrimp couldn’t withstand its own blows. Here too, evolution has provided an answer. The mantis shrimp’s club is composed of layers of chitin reinforced with mineralized fiber arranged in a herringbone pattern, much like carbon fiber used in aerospace technology.

This structure absorbs shock and distributes force evenly, preventing cracks. Even under repeated impacts that would shatter other materials, the mantis shrimp’s club remains intact. Scientists have studied this design in efforts to create tougher military armor, more resilient aircraft materials, and even next-generation body armor.

In essence, the mantis shrimp is not just nature’s boxer—it is nature’s engineer.

A Mind for Combat

Beneath their armor and weapons, mantis shrimp also display signs of intelligence and memory. They are territorial and will recognize individual rivals through extended confrontations. Some species engage in ritualized combat, where two opponents square off and measure one another through displays and posturing before escalating to full strikes. This suggests that mantis shrimp don’t strike blindly—they weigh their options, assess opponents, and sometimes choose diplomacy.

In captivity, they can learn to recognize shapes and patterns and even distinguish between different individuals. They are not mindless killing machines—they are thinking predators with a surprising capacity for learning.

Cracking Shells and Shattering Science

The impact of mantis shrimp research goes far beyond marine biology. Their punch has influenced fields from materials science to robotics, medicine to aerospace. Engineers at UC Riverside and other institutions have used the mantis shrimp’s club as inspiration to design impact-resistant materials for helmets and vehicle armor.

Meanwhile, their spring-loading appendage has inspired robotic arms that can perform precise, powerful tasks in tight spaces. By mimicking nature’s design, researchers hope to build machines that pack strength into small forms, just as the mantis shrimp does.

And in the world of fluid dynamics, the study of cavitation has been revolutionized by these animals. They are not only masters of mechanics—they are teachers of science.

Fragile Giants of the Reef

Despite their ferocity, mantis shrimp are vulnerable. They rely on healthy coral reefs and warm coastal waters to thrive. Climate change, ocean acidification, and reef destruction threaten their habitats. Like many marine species, their future is uncertain in a rapidly warming world.

Yet the mantis shrimp remains a symbol of evolutionary brilliance—a creature shaped by millions of years into something that defies expectation. It reminds us that power can come in small packages, that strength is not always visible, and that nature’s greatest inventions often lie hidden in the sand, waiting.

The Unseen Hero

We tend to look toward lions, tigers, eagles, and sharks as apex predators—symbols of raw power. But the mantis shrimp, no bigger than a pencil case, exists in a realm of force and speed that no terrestrial animal can match. It is the closest thing biology has produced to a biomechanical weapon.

To witness a mantis shrimp strike is to watch nature in overdrive—a ballet of physics, chemistry, and biology played out in milliseconds. It is a reminder that wonder doesn’t always roar. Sometimes, it punches.

And in that moment of explosive motion—when the club hammers down and the sea itself erupts—evolution speaks with clarity: there is genius in every corner of life, even in a burrow beneath the waves.