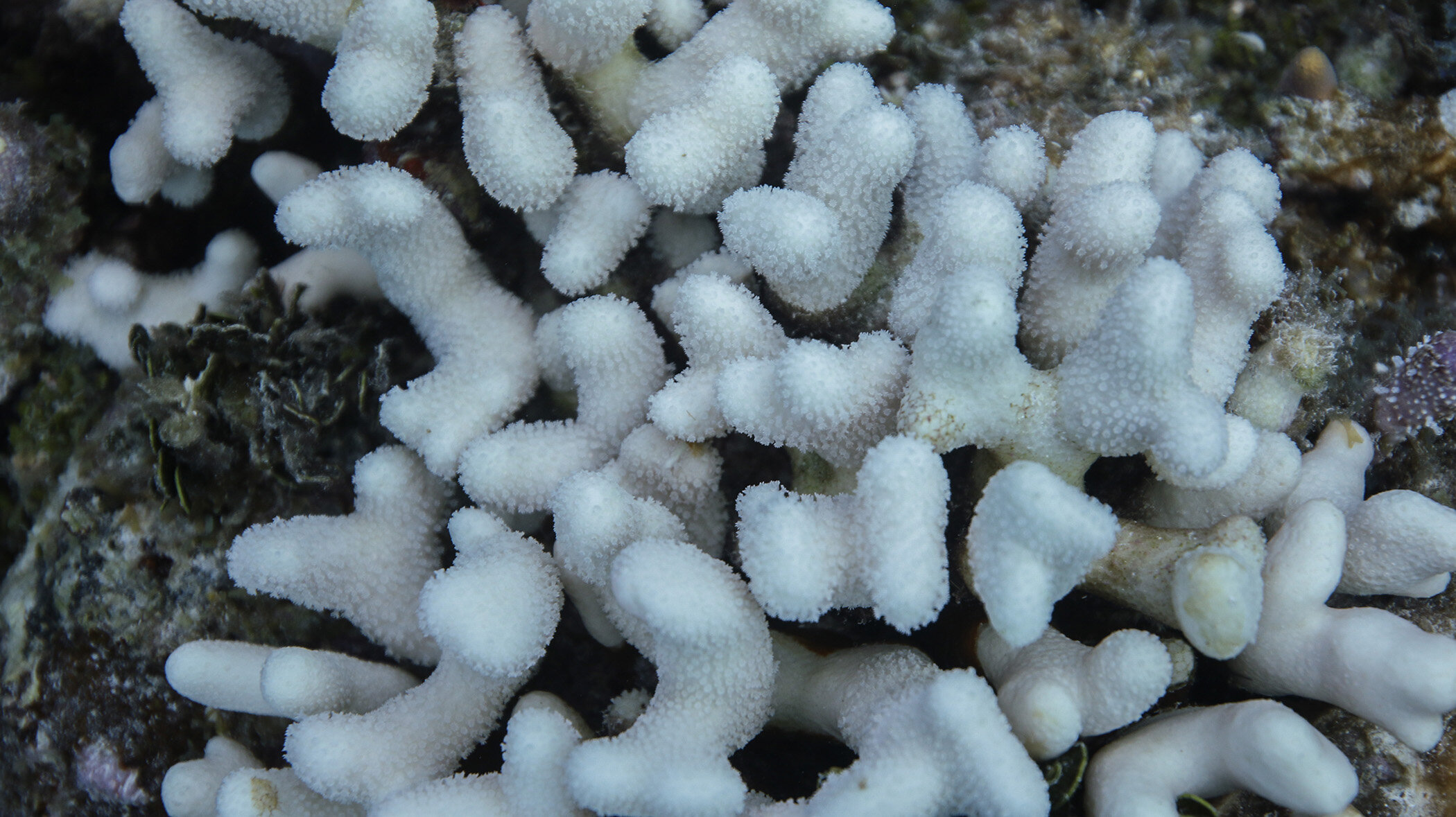

In the summer of 2023, the water off Florida was not merely warm — it was lethal. Divers descending into what once shimmered with living architecture found instead a skeletal silence. Staghorn and elkhorn corals, once the spine and scaffold of Caribbean reefs, were not simply damaged; they were gone in all the ways that matter. The few survivors left behind could no longer build reefs, no longer house fish, no longer slow the force of the sea. They existed, but they no longer functioned. Scientists call that stage functional extinction — the light is still on, but the house is empty.

This was not an isolated tragedy. The 2023 heat wave marked the ninth mass bleaching event to hit Florida’s reefs and the most destructive on record. It was the kind of event climate models warned might arrive decades from now — yet it is here already, and it has arrived with acceleration.

Why Acropora Matters

Coral reefs are not decorative. They are infrastructure. Elkhorn and staghorn corals in particular have built the very shape of Caribbean reefscapes for thousands of years. Their branches form nurseries for fish, armor for coastlines, and foundations for entire ecological networks. Remove them, and the reef does not slowly fade. It collapses.

Once, these corals grew so densely that ships would run aground on them. In just one human lifetime, they have been reduced to remnants — not by one cause but by many: disease, pollution, invasive species, past bleaching events, and now, a level of heat that nature never prepared them to endure.

The Heat Wave That Broke the Record — and the Reef

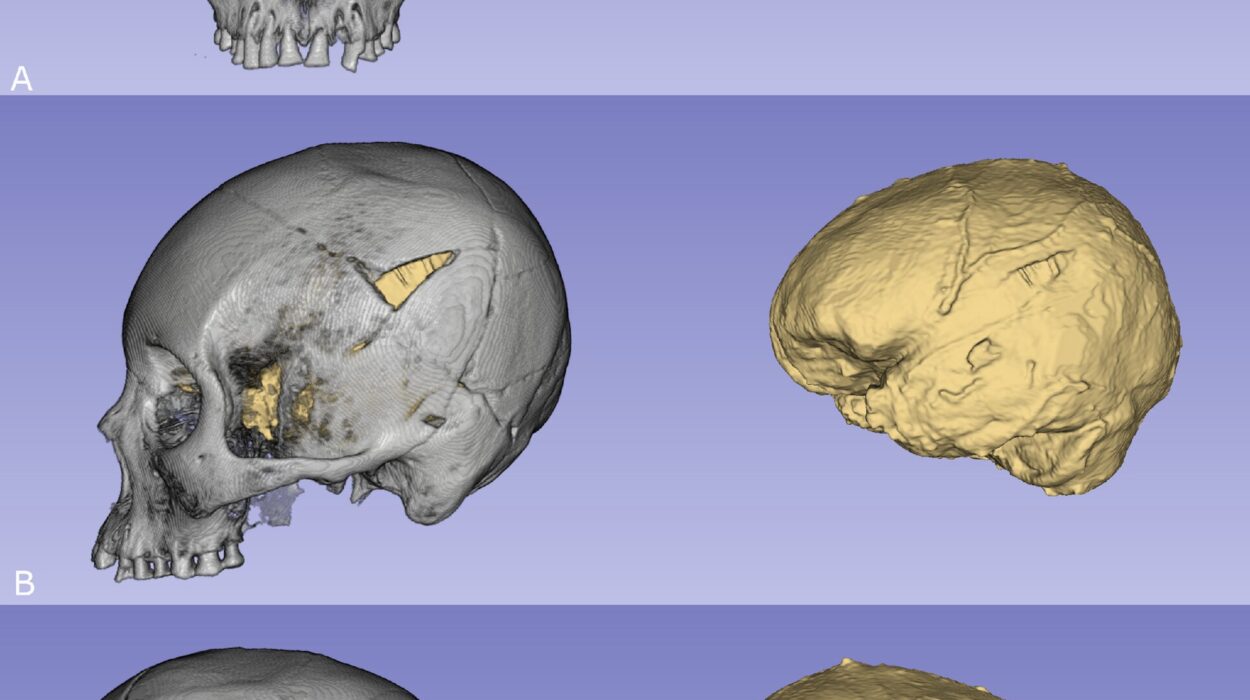

The new study published in Science reads like a forensic report of an ecological disaster. Temperature records over 150 years old show that 2023 produced the hottest conditions ever measured on Florida’s Coral Reef. Heat stress lasted not days but months. Exposure levels reached more than double, sometimes quadruple, anything ever recorded.

Researchers surveyed more than 52,000 coral colonies across 391 sites. In the Florida Keys and Dry Tortugas, mortality reached 98–100%. Offshore sites fared slightly better, but “better” still meant mass death: 38% mortality in South Florida reefs once thought buffered by deeper or cooler waters. In ecological terms, these do not represent losses. They represent collapse.

Functional Extinction Is a Precursor to the Final One

A species becomes functionally extinct not when the last individual dies, but when the survivors are too few to maintain the role that once sustained ecosystems. That threshold has now been crossed for Florida’s Acropora. Species hovering at this stage rarely recover without dramatic human intervention — and even then, time itself can run out before help arrives.

As Dr. Ross Cunning of Shedd Aquarium warned, the trajectory is clear: heat waves are becoming more frequent and more severe, and without immediate action, more coral species will follow the same path into silence.

An Ark for the Future — and Its Limitations

Because the reef can no longer save itself, humans have begun to build an artificial lifeboat. Scientists maintain living repositories of Acropora — fragments protected in aquariums and offshore nurseries, genetic backups in case the ocean becomes hospitable again. After the 2023 heat wave, more surviving fragments were rescued to bolster these bio-banks.

But banking is not rebuilding. Restoration efforts now face a new and harsher truth: without reducing heat, restoration is a race run on melting ground. Even the strongest fragments will bleach again if oceans continue to warm. If future heat waves return sooner than expected, gene banks will be studios of ghosts — growing organisms destined for waters that can’t receive them.

It Will Take More Than Restoration

Conservation alone — planting fragments, guarding survivors — is no longer enough. Scientists now speak of interventions that would once have sounded radical: importing more heat-tolerant genetic strains from other regions, or modifying the algae that corals host to make them better at withstanding extreme heat. These are emergency measures for a patient in full organ failure.

But even these adaptive strategies cannot compensate for a planet that continues to warm. Without large-scale climate action, every nursery and every gene bank will eventually be overtaken by the same thermodynamic reality.

A Local Tragedy With Global Implications

Florida’s reef is not merely a geographic case study. It is a preview. The loss of its Acropora corals is both a warning and a proof: climate change is now exceeding the biological limits of some of Earth’s most ancient living systems. Once these builders vanish, the ecosystems they created unravel. And reefs are not alone — forests, glaciers, kelp beds, river deltas — all share the same vulnerability to thresholds beyond which return becomes impossible.

The study’s authors do not write in metaphor, but its implications are poetic in the bleakest way: an entire ecosystem has reached the edge of time faster than expected.

The Meaning of a Reef’s Silence

To lose a reef is to lose more than a habitat. It is to lose a living coastal defense, a nursery for a quarter of all marine life, a carbon sink, a food source, a livelihood for millions, a biological archive of evolutionary brilliance. It is to watch a structure built over millennia collapse in a single summer.

The death of coral is not loud. There is no smoke, no sirens, no broadcast. It ends the way bedrock erodes — slowly, then all at once. But when the reef goes silent, the ocean around it begins to unmake itself.

The Window That Is Still Open

The future is not yet sealed, but the margin is narrow. Two things must happen together: reefs must be given every possible intervention to survive the next decade, and the drivers of ocean warming must be slowed with the same urgency normally reserved for war or plague. The pace of heat must be reduced before the biological clock runs out.

The story of Florida’s Acropora is not only a record of loss — it is a test of whether humanity will act while action still matters. The reef did not fail on its own. And it will not recover on its own. The question that remains is not whether we understand the danger. It is whether we respond before the silence spreads.

More information: Derek P. Manzello et al, Heat-driven functional extinction of Caribbean Acropora corals from Florida’s Coral Reef, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adx7825