When we think of fossils, we often imagine the towering skeletons of dinosaurs or the fierce teeth of saber-toothed cats. But buried in Earth’s sediments lie quieter, more delicate remains—tiny fish ear bones, grain-sized shark scales, and coral scars—that whisper stories just as profound. In the crystal waters of the ancient Caribbean, long before humans ever dropped a fishing line into the sea, coral reefs thrived with a complex balance of predators and prey. That balance, new research shows, has been dramatically rewritten by human hands.

A groundbreaking study from the Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute (STRI), published in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, offers the first fossil-based proof of how centuries of human fishing have reshaped the very structure of reef ecosystems. Drawing from a remarkable archive of 7,000-year-old fossil reefs in Panama’s Bocas del Toro Province and the Dominican Republic, scientists pieced together a vivid portrait of coral reef life before human interference—and compared it to the reefs we see today.

The findings are as stunning as they are sobering: sharks, once dominant rulers of the reef, have declined by 75%. Fish targeted by humans are now, on average, 22% smaller. And as predators disappeared, their prey flourished—doubling in numbers and growing in size. These cascading changes, long theorized but never directly observed, reveal how deeply human fishing has rippled through the reef food web.

Fossils That Speak Volumes

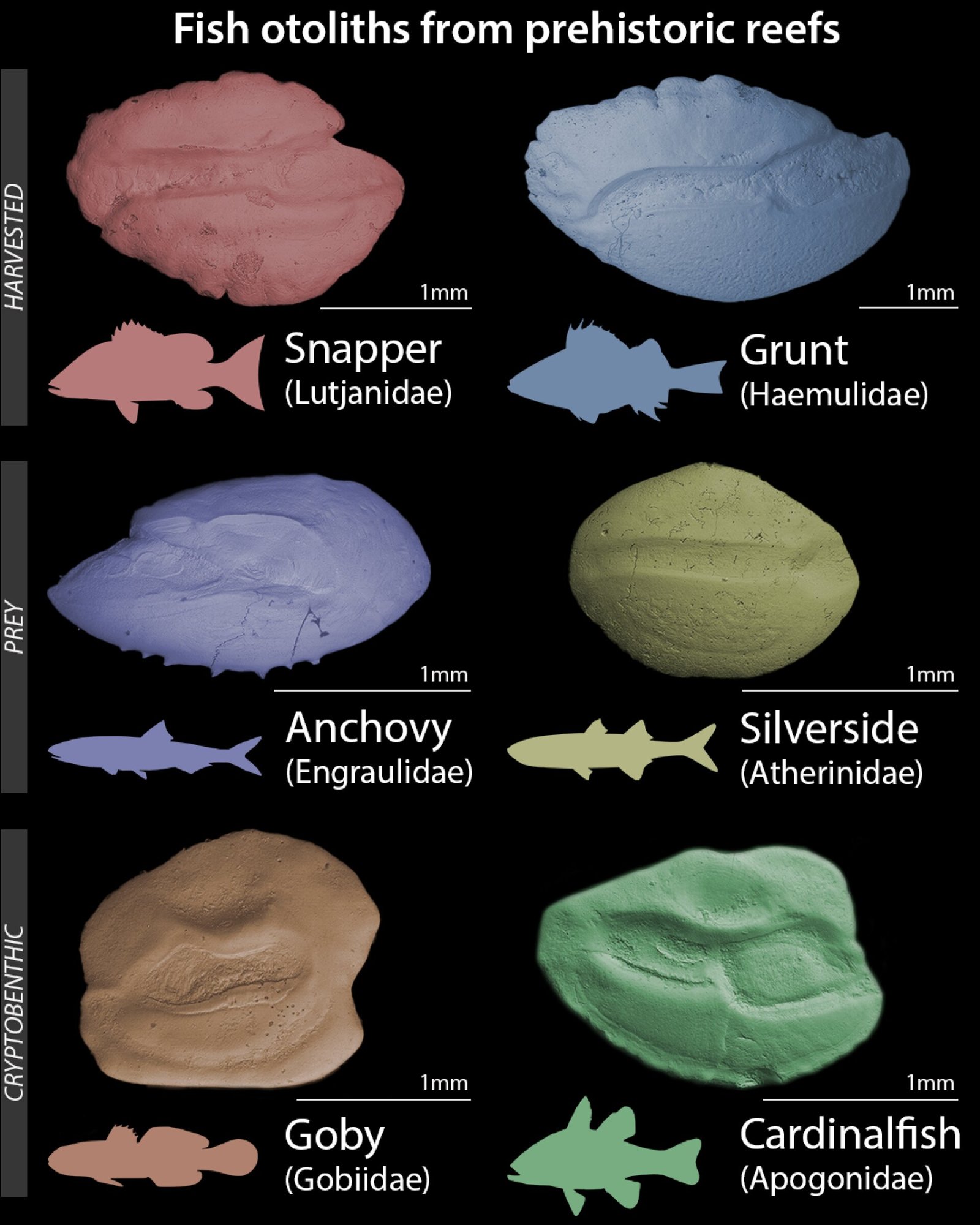

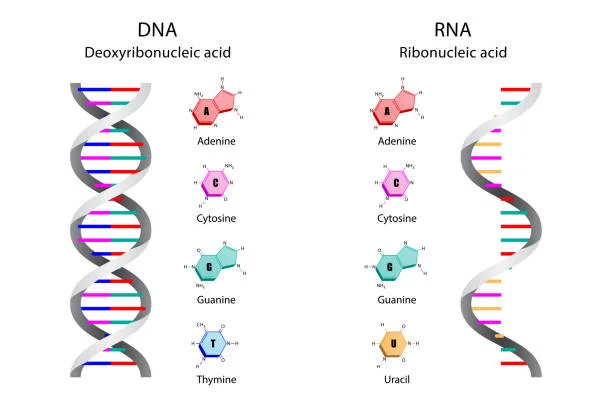

To unlock this hidden history, the research team didn’t look for bones the size of tree trunks. Instead, they combed through the fine sediments of ancient coral reef deposits, sifting out hundreds of shark dermal denticles—tiny, tooth-like scales that once gave shark skin its sandpaper feel—and thousands of minuscule otoliths, the calcium carbonate ear stones that help fish maintain balance.

Each otolith grows in concentric layers, like tree rings, and from these layers scientists can estimate the size of fish at death. In total, the researchers analyzed 807 shark scales and 5,724 otoliths. This was not a study of giants, but of whispers—meticulous reconstructions of ecosystems built from the tiniest surviving clues.

The results told a powerful story. Over the past seven millennia, the biggest predators—sharks and large carnivorous fish—have nearly vanished. In their place, prey fish species that were once tightly controlled by predation have surged in number and size. The researchers even tracked damselfish bite marks on fossilized and modern coral branches, finding significantly more bites today—a sign of increased prey fish activity on modern reefs.

The Predator Release Effect Comes to Life

Ecologists have long theorized what’s called the “predator release effect”: when top predators are removed from an ecosystem, their prey population grows rapidly, often altering the environment in the process. It’s been observed in terrestrial systems—like deer populations exploding after wolf declines—but until now, hard historical evidence of this effect in marine reefs was scarce.

This study provides the first fossil-based confirmation of that theory in reef environments. By comparing ancient and modern reefs side by side, the scientists could isolate the role of predation from other environmental changes like pollution or habitat loss.

“This is one of the clearest examples of predator release ever documented in the ocean,” said the researchers. “We now have a fossilized snapshot of what reefs looked like before humans started overfishing, and we can clearly see how the removal of sharks cascaded through the food web.”

Winners, Losers, and the Survivors

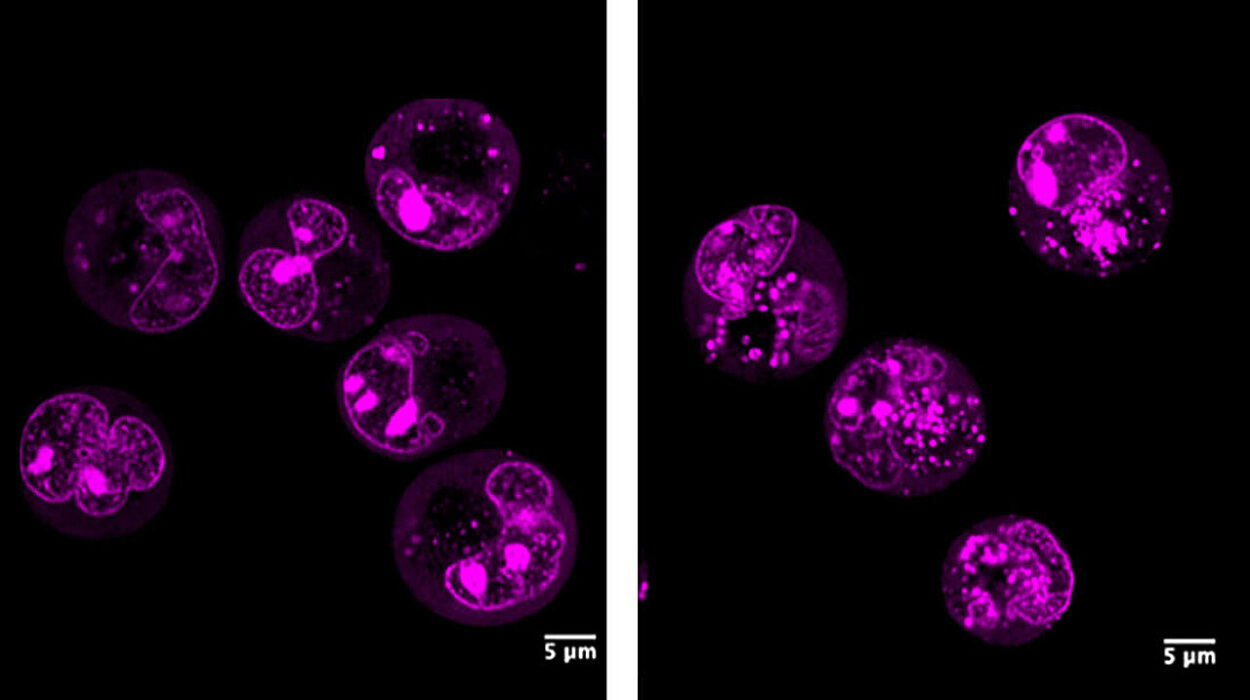

The story unfolding in Caribbean reefs is not just one of loss—it’s also one of resilience. While exposed prey fish (those living in open reef areas) became more abundant and larger over time, another group—the cryptobenthic fishes—remained unchanged. These tiny, elusive fish live deep within coral crevices, hidden from both predators and researchers. Their numbers and size have stayed consistent for over 7,000 years.

This resilience suggests that not all parts of the reef food web respond to change in the same way. The cryptobenthic fish, shielded by the architecture of the reef itself, appear to have been buffered from both natural environmental shifts and human disruption. Their unchanging story offers a glimmer of hope—a signal that some reef species may endure, even as ecosystems around them transform.

Fishing’s Long Shadow

Caribbean reefs have faced increasing pressure from human activity for centuries. Industrial fishing, in particular, has targeted large predatory fish, including reef sharks, groupers, and snappers—species that once regulated the balance of coral reef communities. As these predators disappeared, the checks and balances that kept prey fish populations in equilibrium unraveled.

The modern reefs of the Caribbean now bear little resemblance to their ancient selves. Large predatory fish are rare. Prey fish species, such as damselfish, parrotfish, and wrasses, are more numerous and grow larger in the absence of threats. But this isn’t just a shift in species—it’s a restructuring of entire ecosystems. The delicate dance between predator and prey, refined over millions of years, has been rewritten in just a few hundred.

Why the Past Matters for the Future

One of the most powerful contributions of this study is the establishment of a true ecological baseline—an understanding of what healthy, pre-human reefs looked like. Without such a baseline, conservation efforts risk targeting an already degraded ecosystem as the “norm.”

These ancient reefs reveal what’s been lost and what might still be recovered. By identifying which species and interactions have changed—and which have persisted—scientists can more accurately predict how reefs might respond to conservation strategies, habitat restoration, or further environmental stressors like climate change.

“This study demonstrates the power of the fossil record for future conservation,” the authors wrote. “It’s not enough to protect what we have now—we need to understand what we once had, and what’s truly natural.”

The Silent Testimony of Coral and Bone

In the stillness of fossil beds buried beneath tropical sands, ancient stories wait patiently for science to listen. The coral reefs of the Caribbean, once alive with the thrum of sharks and the choreography of prey, now echo with imbalance. But thanks to this research, we can finally hear the full story.

The message is clear: the loss of predators is not just a numbers game. It transforms the very architecture of life. But in that transformation lies knowledge—of resilience, of fragility, and of the interconnectedness that binds all species in a living reef.

If we are to restore what has been lost, we must start by seeing clearly what once was. And sometimes, that vision begins not with a grand skeleton—but with a grain of bone, a flake of scale, and a bite mark on ancient coral.

Reference: Aaron O’Dea et al, Prehistoric archives reveal evidence of predator loss and prey release in Caribbean reef fish communities, Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1073/pnas.2503986122