In the vastness of the world’s oceans, where humans are often mere spectators to the deep blue mysteries below, a surprising behavior is emerging from one of the sea’s most powerful predators. Orcas—commonly called killer whales—may not just be apex hunters. They might also be…gift givers.

In a new study published in the Journal of Comparative Psychology, scientists report something both scientifically fascinating and emotionally evocative: wild orcas have been observed offering their prey—fish, stingrays, and even chunks of large animals—to humans. And not just once or twice. Over the last two decades, researchers recorded 34 such encounters across the globe, suggesting that this behavior might not be a fluke but something far more intentional.

“It’s as if the orcas are saying, ‘Here, I want you to have this,’” said Jared Towers, lead author of the study and director of Bay Cetology, a Canadian organization dedicated to the study of whales and dolphins. “They do this with each other, and it seems they might be extending that social gesture to us.”

Gifts From the Deep

The incidents span a geographic range as wide as the whales’ own migratory routes—California, Norway, New Zealand, Patagonia—and in every case, the whales made the first move. The humans involved weren’t diving into their space or tossing bait into the sea. In fact, the study required that all interactions met strict criteria: the orcas had to approach humans voluntarily and present the item without coercion or previous feeding.

In 11 of the 34 cases, people were in the water. In 21, they were on boats. Two happened from land. Some were caught on film. Others were relayed through detailed interviews. But the pattern was unmistakable.

In one encounter off the coast of New Zealand, an orca approached a diver and gently dropped a freshly caught fish in front of him, then hovered nearby, watching. When the diver didn’t take the offering, the orca circled back, picked it up, and tried again—three times.

“It’s reminiscent of a cat proudly leaving a bird on your doorstep,” said co-author Dr. Ingrid Visser of the Orca Research Trust. “Except instead of a house pet, it’s a 6,000-pound marine predator showing you its generosity.”

More Than Just Meat

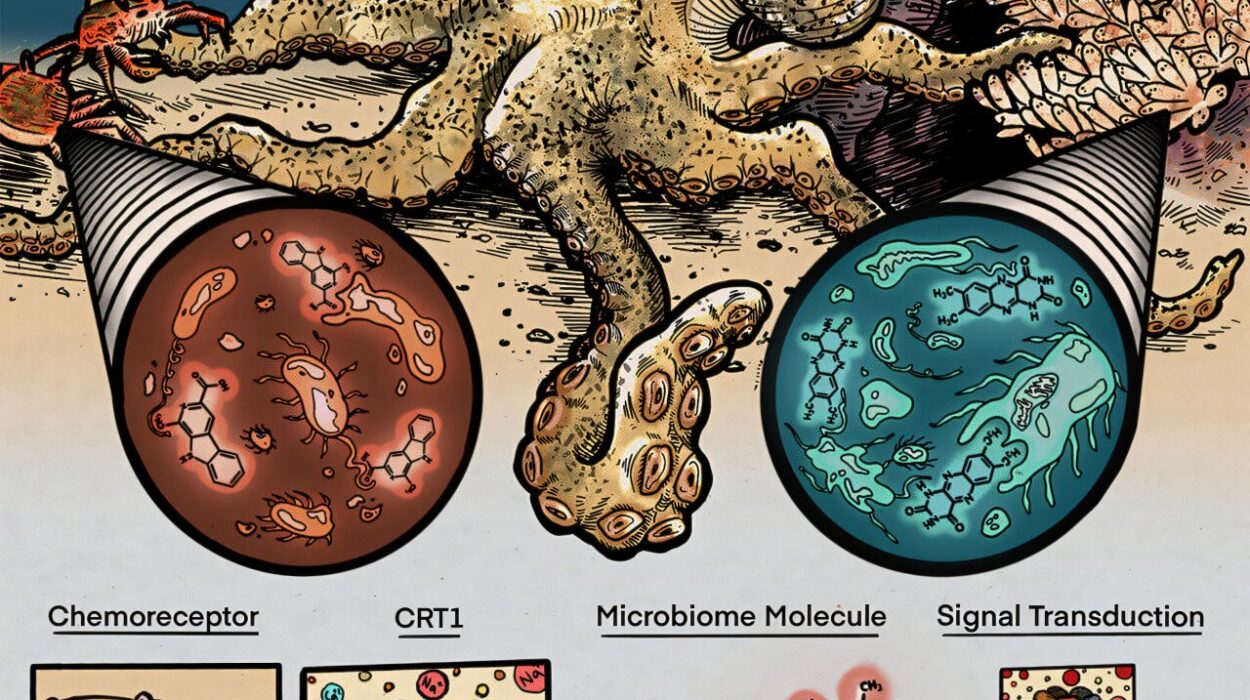

Orcas are known for their intelligence. Their brains are larger than ours, and their social structures are sophisticated and intricate. They live in close-knit pods and pass down knowledge across generations—something scientists call “cultural transmission.” Some pods teach hunting techniques unique to their region. Others share vocal dialects. And, as this new research suggests, some might also be experimenting with interspecies communication.

Food sharing is common among orcas, especially between mothers and calves or among tightly bonded individuals. It’s not always about feeding—it’s about social bonding, trust, even affection. And now, humans might be entering that social sphere.

“The sharing of food among non-domesticated animals with humans is extremely rare,” said Vanessa Prigollini, co-author of the study from the Marine Education Association in Mexico. “That orcas are doing this, with what looks like intent and repetition, is astonishing.”

Playing With Understanding

Why would a wild animal, capable of taking down sharks and swimming thousands of miles, choose to offer part of its meal to a human?

The researchers suggest several possible explanations. The whales could be practicing cultural behavior—learned patterns that may have social or cognitive functions. They could be playing, testing our reactions, or trying to understand us in the same way we strive to understand them. Or it might be an attempt to create a bond, a silent invitation to bridge the species gap.

“Given their cognitive complexity,” the study reads, “it is entirely plausible that killer whales engage in these behaviors to explore or develop relationships with humans.”

And the orcas seem patient. In all but one of the 34 cases, the whales waited after offering their food—watching, perhaps hoping. In seven incidents, they tried multiple times. This kind of persistence mirrors behaviors seen in other intelligent species, like primates and dolphins, where communication and social learning are vital.

The Power of Interconnection

These findings land at a time when the human relationship with nature is both more fragile and more urgent than ever. Orcas, once demonized in films and misunderstood in culture, are increasingly seen for what they truly are—sentient, social beings with rich emotional lives and complex minds.

They have been observed mourning their dead, teaching their young, and adapting their behaviors to survive in changing oceans. And now, they may be offering us more than food. They might be offering connection.

“This is a reminder,” Towers says, “that we’re not alone in our capacity to relate, to empathize, to reach out beyond our species. We’re not the only ones who seek to understand. We’re not the only ones who give.”

Science Meets Soul

For marine biologists, the study opens new doors into understanding cetacean cognition and social behavior. For the public, it offers a story that cuts through cynicism and fear, one that reminds us how extraordinary the world still is.

And maybe, just maybe, the next time you’re on a boat and an orca rises from the depths with a gift in its mouth, you’ll recognize it not as a spectacle—but as a message.

One that says: I see you. Do you see me?

Reference: Jared R. Towers et al, Testing the waters: Attempts by wild killer whales (Orcinus orca) to provision people (Homo sapiens)., Journal of Comparative Psychology (2025). DOI: 10.1037/com0000422