Beneath our feet lie the scattered bones of history—stone-turned echoes of lives lived long before memory. Fossils whisper the tale of Earth, from trilobites that once crawled across primordial seas to the thunderous reign of the dinosaurs. And yet, in this vast library of life, one chapter seems mysteriously thin. Ours.

Where are the human fossils?

We search the soil for signs of our ancient ancestors, and sometimes we find them. A jawbone here, a femur there. A skull so precious that whole careers revolve around it. These discoveries stun the world not just because of what they tell us, but because of how rare they are. Compared to the fossils of other creatures—fish, reptiles, even tiny invertebrates—human fossils are vanishingly few. The question arises with urgency, tinged with a yearning to know who we are: why don’t we find more human fossils?

The answer unfolds across deep time and deep earth. It’s a tale of biology and geology, of improbable luck and breathtaking patience. But it is also, in many ways, a story of loss—the loss of voices never heard, of faces never seen, of people who once loved, feared, hoped, and vanished without a trace.

The Nature of Fossilization: A Narrow Gate

To understand why human fossils are so rare, we must first understand what a fossil is. Fossils are not mere bones; they are the mineralized remnants of organisms, or impressions left behind, preserved through time by a unique set of conditions. The process of becoming a fossil—called fossilization—is more akin to a miracle than a routine fate.

When an organism dies, decay is swift and inevitable. Bacteria, scavengers, and the elements quickly erase most evidence that life was ever there. To become fossilized, remains must escape this gauntlet. They must be buried quickly and deeply—often by sediment, volcanic ash, or silt in watery environments. This rapid burial protects them from decomposition and physical destruction. Over millennia, the surrounding minerals seep into the bone, replacing organic material and hardening into stone.

But this path to preservation is not open to all. In fact, it’s estimated that fewer than one in a billion organisms ever fossilize. For humans and our ancient relatives, that number is likely even smaller. Not only do we lack some of the advantages that aid fossilization, but we’ve only been around for the briefest flicker in geological time.

The Geological Clock Is Not on Our Side

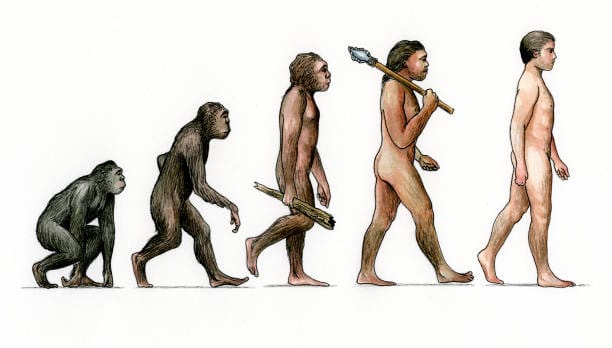

The fossil record stretches back more than 3.5 billion years. That’s a mind-bending span of time, encompassing nearly the entire history of life on Earth. But anatomically modern humans—Homo sapiens—have existed for only about 300,000 years. That’s less than 0.01% of Earth’s biological history.

Even when we expand the category to include our hominin ancestors, such as Australopithecus, Homo habilis, and Homo erectus, we still find ourselves occupying a very narrow window—perhaps six or seven million years in total. In contrast, many species of dinosaurs thrived for tens of millions of years. Some marine invertebrates left fossils across hundreds of millions of years. Simply put, we haven’t been around long enough to leave behind the kind of fossil abundance other species have.

Compounding this temporal disadvantage is the fact that many of the human fossils we seek are from relatively recent epochs—mostly the Pliocene, Pleistocene, and Holocene—geological layers that are still being eroded rather than deeply buried. In many places, these younger strata haven’t yet entered the deep fossil-rich zones of the Earth’s crust, and therefore, much of the potential record hasn’t been preserved or even reached by paleontologists.

Our Habits Didn’t Help

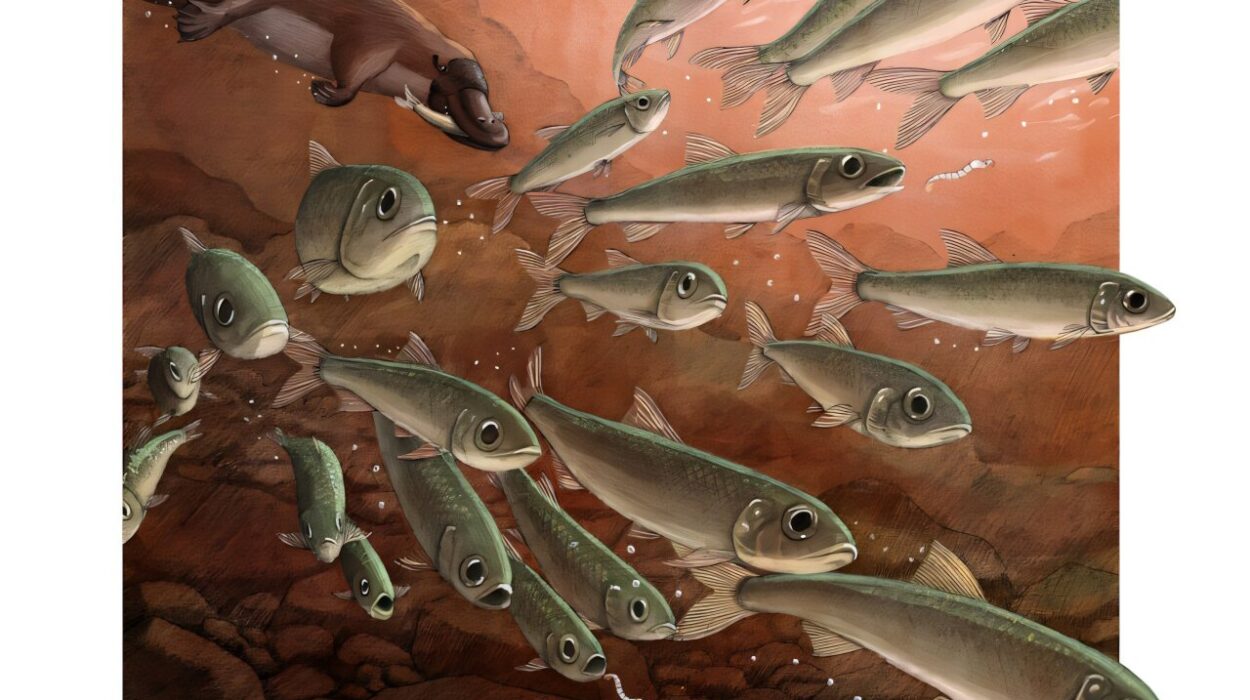

When early fish and marine organisms died, they often sank into mud-rich environments perfect for fossilization. Dinosaurs, too, sometimes died near lakes, floodplains, or were caught in river floods, entombed in sediments. But humans? We did not often die in those kinds of places.

Our ancestors were mobile, adaptive, and largely land-dwelling. We migrated across dry savannas, through forests, over rocky terrain. These are not places conducive to the rapid burial required for fossilization. Instead, the open-air settings where ancient humans lived and died were subject to wind, erosion, and scavengers. Even burial, which seems like it might help, often doesn’t. Shallow graves offer only fleeting protection. Over thousands of years, most of what lies within them is consumed by time.

Then there is the matter of our size and population. For most of our evolutionary history, hominins were not numerous. Small groups scattered across vast landscapes, their populations ebbing and flowing with climate and food supply. Many hominin species likely numbered in the thousands, not millions. By comparison, marine organisms or herding herbivores lived in staggering abundance. The more individuals, the greater the chance that some will fossilize. We were always on the losing side of that equation.

Destruction Before Discovery

Fossils, once formed, face further dangers. Earth is a restless planet. Mountains rise. Rivers shift. Glaciers grind. Plate tectonics rearrange the continents like puzzle pieces in slow motion. And through it all, fossils can be shattered, melted, or buried beyond reach.

In fact, for every fossil we find, it’s likely that countless others have been destroyed by erosion, earthquakes, lava flows, or simply the crushing weight of time. Many have been turned to dust without ever being seen. Human fossils, already rare due to our behaviors and timelines, are especially vulnerable to these geologic fates.

Adding insult to injury, humans themselves have been a force of fossil destruction. Agricultural development, mining, urban expansion—these tear up the land where fossils might rest. In some regions, historical human settlement has paved over crucial fossil beds. Ironically, as we expand our footprint on the planet, we often erase the very traces of how we came to be.

The Fragile Human Frame

There’s another practical reason we don’t find many human fossils: our bones are relatively fragile. Compared to dinosaurs or large mammals like mammoths, human bones are thinner, less dense, and more susceptible to decay and destruction.

The skulls of our ancestors are particularly delicate. The braincase is thin and easily crushed. Teeth tend to survive better, which is why paleoanthropologists often base entire hypotheses on a handful of molars. Post-cranial remains—like ribs, vertebrae, and small hand bones—are even rarer and harder to interpret.

When we do find a well-preserved human fossil, it’s often due to some exceptional set of circumstances: burial in volcanic ash (as with Homo erectus in Java), entrapment in tar pits (like the La Brea remains), or preservation in caves, where environmental conditions slow decay. But these are exceptions, not norms.

A Trail of Clues, Not a Crowd of Corpses

Despite all these challenges, the fossil record of human evolution is richer than it first appears. It’s not filled with legions of skeletons, but with a trail of precious clues—scattered bones, skull fragments, and partial skeletons that together form the puzzle of our past.

From Ardipithecus ramidus, a 4.4-million-year-old hominin with a foot in both trees and ground, to Australopithecus afarensis, best known by the famed skeleton “Lucy,” we’ve begun to piece together a lineage of astonishing resilience and adaptation. Homo habilis, the “handy man,” showed signs of tool use. Homo erectus walked upright, controlled fire, and left Africa to explore Asia. Neanderthals and Denisovans left behind traces not only in caves but in our DNA.

Each find is a marvel, not just for its rarity, but for what it represents: a single dot in the vast constellation of human becoming. The gaps are many, but the stars shine nonetheless.

Genetic Fossils: The New Archive

In recent decades, another kind of fossil has begun to rewrite our understanding of the past—one made not of stone, but of molecules. Our DNA.

Genetics has opened a new window into human evolution. By comparing the genomes of living people and ancient remains, scientists can infer migrations, interbreeding events, and evolutionary changes. For instance, we now know that modern humans interbred with Neanderthals and Denisovans, adding their genes to our own. These genetic legacies are, in a sense, living fossils—evidence of ancient contact preserved not in rock, but in blood.

Genetic data can also compensate for missing fossils. Even when we lack bones, we can reconstruct family trees, estimate divergence times, and trace migrations across continents. The genetic approach doesn’t replace the need for fossils, but it adds powerful new tools to the search.

Every Fossil Is a Revolution

The rarity of human fossils means that every discovery carries immense weight. A single bone can overturn theories, spark new debates, or rewrite timelines. The 1974 discovery of “Lucy” in Ethiopia revealed that bipedalism evolved long before large brains. The 2015 find of Homo naledi in a South African cave introduced a species with a puzzling mix of primitive and advanced features. Even more recently, Denisovan remains—at first only a finger bone and a tooth—forced scientists to acknowledge a new branch of the human family tree entirely.

This is part of what makes paleoanthropology so thrilling and humbling. We are constructing a cathedral of knowledge from ruins, dust, and shadows. And yet, what we build is real. Every layer adds depth to the story of who we are.

Why It Matters

Some may ask: why does it matter whether we find more human fossils? Isn’t the past just that—the past?

But this question misses the heart of the matter. To study our ancestors is to seek understanding of ourselves. Where we came from. How we became what we are. What we share with those who walked before. The search is not about curiosity alone; it’s about meaning.

In a fractured world, the fossil record reminds us that all modern humans share a common origin. That race is a social construct, not a biological truth. That survival is not about dominance, but adaptation. That intelligence is not linear, but multifaceted. And that culture, compassion, and community have always been part of our story.

Each fossil, however rare, is a mirror. It shows us not just bones, but the soul of a species that has always wondered, always wandered, always yearned for more.

The Fossils Yet to Be Found

Despite the odds, the search continues. Fossil-rich regions in Africa, Asia, and Europe still yield surprises. New technologies—ground-penetrating radar, satellite imagery, and advanced excavation methods—are enhancing our ability to find what was once hidden. And global cooperation among scientists is helping ensure that these discoveries are studied and preserved with care.

But many fossils—perhaps most—will never be found. Time has claimed them. That knowledge should not discourage us; it should deepen our reverence. Because when we do find one—just one—it is an extraordinary gift from the past.

The bones of our ancestors are not just stone. They are testimony. They are reminders. They are, in a profound sense, us.

And perhaps that’s the final answer to why we so rarely find human fossils: because we ourselves are the living fossils of those who came before.