For over 150 million years, their bones have been locked away in stone — silent witnesses to seas long vanished. Now, thanks to painstaking work by paleontologist Dr. Martin Ebert, two newly described fish species from the mysterious genus Thrissops have emerged from the fossil record, offering a rare window into the lives and environments of some of the earliest modern fish.

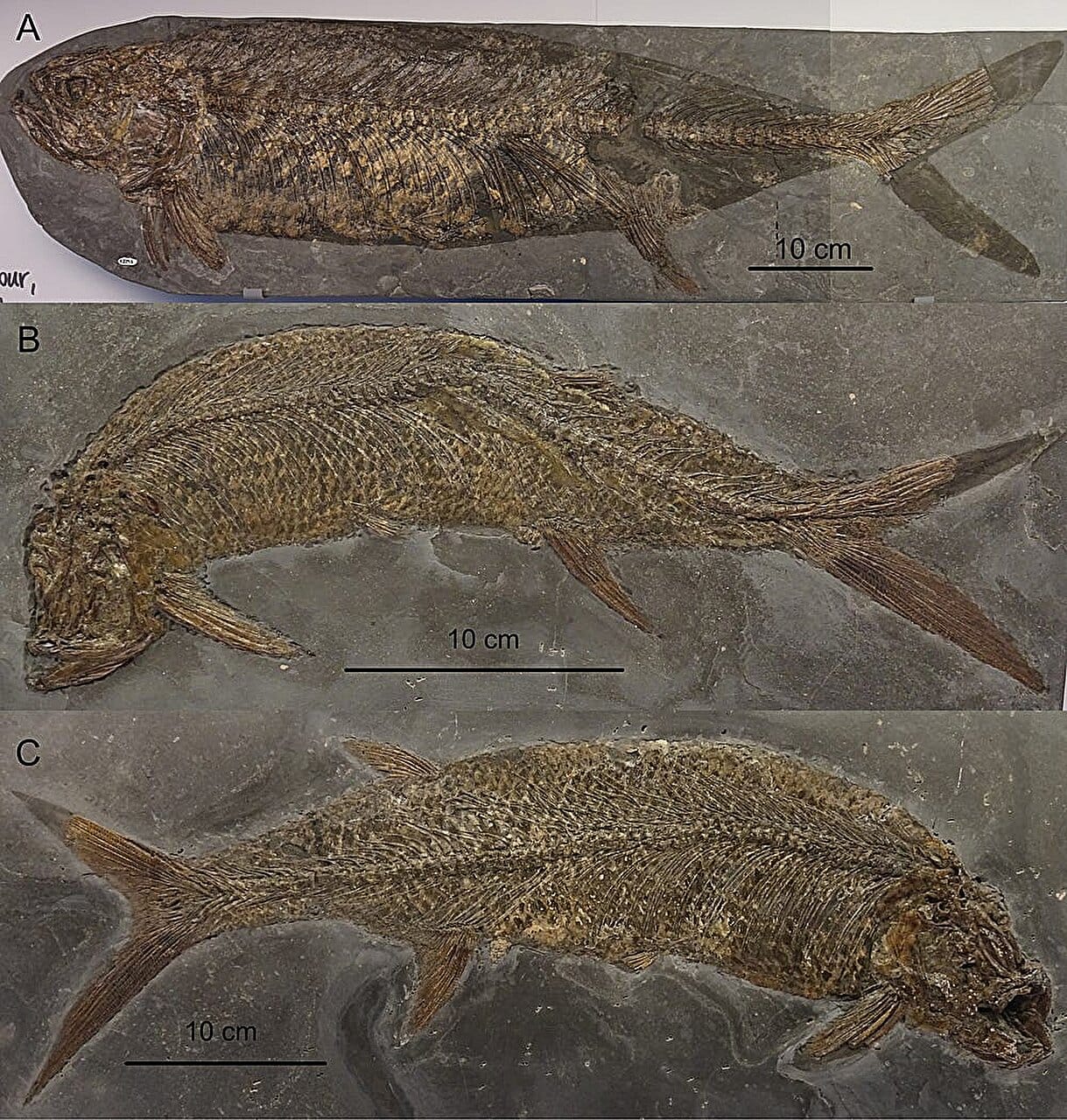

Published in the journal Zitteliana, Dr. Ebert’s research details the discovery of Thrissops ettlingensis sp. nov. from Germany’s lower marine Tithonian Plattenkalk of Ettling, and Thrissops kimmeridgensis sp. nov. from England’s Kimmeridge Clay. Despite being separated by hundreds of kilometers in life — and now millions of years in time — the two species belonged to the same ancient order, the Ichthyodectiformes, and swam Earth’s oceans at the height of the Late Jurassic.

A Family Tree Stretching Back to the Dawn of Modern Fish

Both species are part of Teleostei, a group that dominates the waters today with more than 96% of all living fish species, from tropical reef dwellers to freshwater salmon. Teleosts are evolutionary survivors, with fossil roots reaching back to the Triassic period around 250 million years ago.

Among the earliest teleost lineages was the Ichthyodectiformes — a cosmopolitan order known from every continent, thriving from the Mid-Jurassic through to the extinction events of the Late Cretaceous. Their anatomy was distinctive: a specialized tail skeleton, an unusual skull bone called the ethmopalatine, long anal fins, and small dorsal fins set far back on the body, often behind the anal fin. These were agile predators built for speed.

The two new species described by Dr. Ebert fit neatly into this order, but also challenge some long-held assumptions about Thrissops anatomy, ecology, and even their appearance.

The Ettling Discovery — A Rare Glimpse of Youth

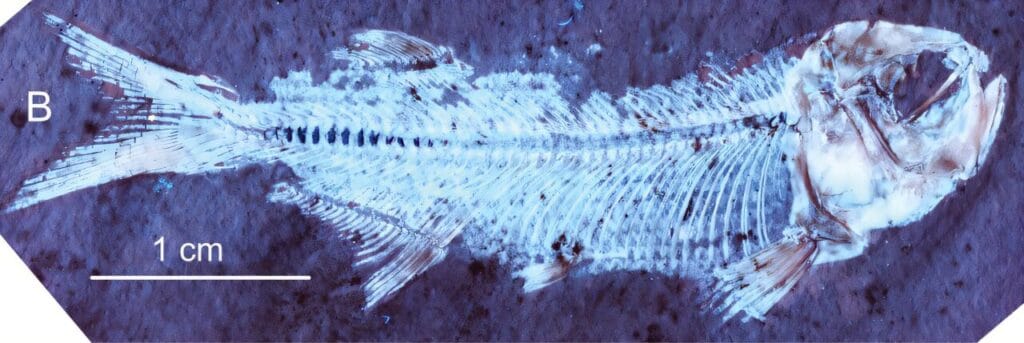

The story of Thrissops ettlingensis begins in the fine-grained limestone of Ettling, Germany. Here, seven remarkably preserved specimens came to light — including the only known juvenile Thrissops ever found.

“I realized that the juveniles of Thrissops lived somewhere else,” Dr. Ebert explained. “From other Teleostei of the Solnhofen Archipelago, we have a lot of juveniles in the fossil record, sometimes up to 50%.” In contrast, Thrissops appears to have kept its young away from the shallow basins where adults thrived.

The Ettling specimens are exceptional in another way: several preserve not just bones, but stomach contents and even traces of color. Two individuals still carried their last meals — Orthogonikleithrus hoelli, a small fish — inside their stomachs, their vertebrae still connected, suggesting they had been swallowed only shortly before death.

Some scales also preserve dark pigment — melanin — revealing patterns similar to those of another species, Thrissops formosus. For paleontologists, such rare preservation is a goldmine, allowing reconstructions of Jurassic fish in far greater detail than bones alone can offer.

The Dorset Find — Giants of the Jurassic Seas

Meanwhile, along England’s Dorset coast, the story of Thrissops kimmeridgensis unfolded in a different kind of marine world. Over 80 fossils recovered from the Kimmeridge Clay — many collected by fossil expert Steve Etches — tell a tale of deep-water predators and dangerous lives.

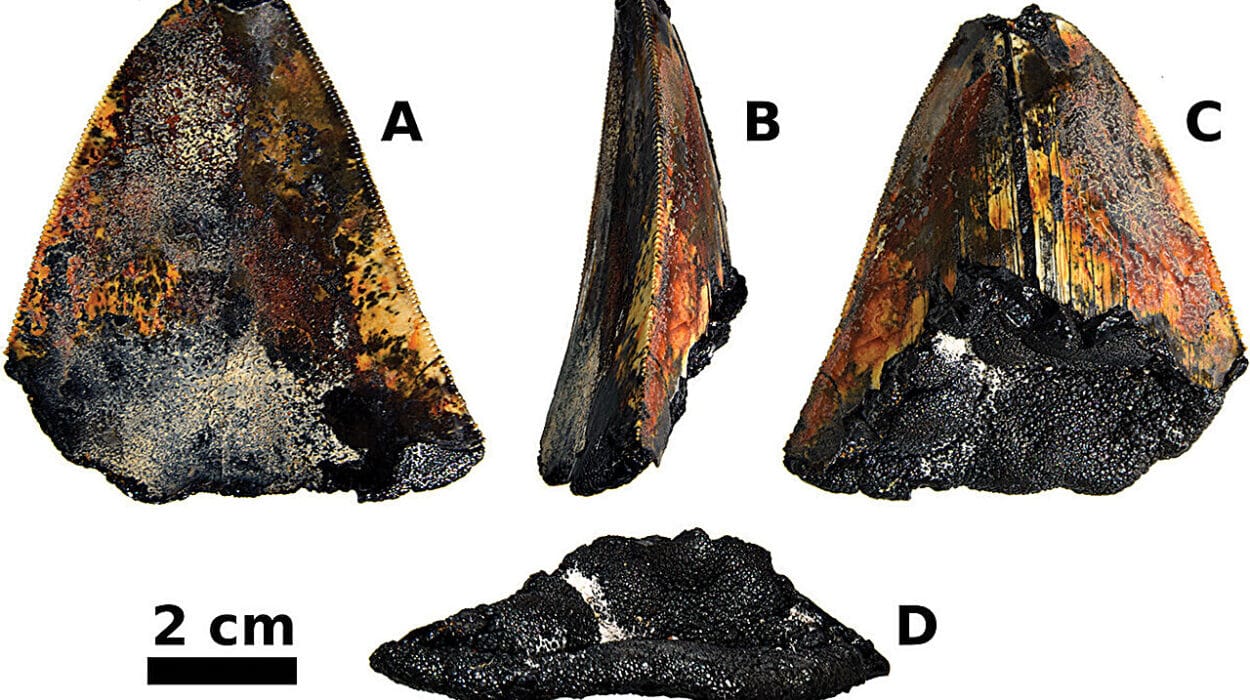

Here, Thrissops remains were often found as isolated skulls or tail fins, hinting at an ancient food web in which larger predators feasted on these fish. “In the open water, there was probably enough food for larger predators, which also fed on the abundant Thrissops,” Dr. Ebert noted.

This species stood out not only for its size — the largest Thrissops known — but also for distinctive features such as irregular lower jaw teeth. Its overall proportions closely matched those of Th. formosus, but without the elongated bodies and saber-like fin rays seen in some Thrissops relatives.

Why These Discoveries Matter

The two new species provide more than just names in a fossil catalog. They help scientists trace the early diversification of Teleostei, revealing variations in body form, feeding habits, and even habitat preferences within a single genus.

Equally important, they shed light on the ecology of the Late Jurassic seas — complex worlds where fish species specialized in different niches, juvenile and adult stages could live apart, and predators lurked at every depth.

Dr. Ebert hopes these finds will contribute to a future phylogeny — a family tree — that includes the new species and clarifies how Thrissops and its relatives evolved. But his broader ambition is to understand the diversity and distribution of Jurassic fish on a global scale.

“There are sites where certain genera are common or rare, which also applies to the genus Thrissops,” he said. “That tells us a lot. For this comparison of fish faunas, I have now reviewed about 100 collections and have a database with more than 23,000 fish specimens. Most of them, I have updated the taxon names.”

A Glimpse Into a Lost World

From the shallow, sunlit basins of the Solnhofen Archipelago to the deep, predator-rich waters of the Kimmeridge Clay, Thrissops swam in oceans utterly different from our own. And yet, in their anatomy and behavior, they offer familiar echoes of the fish that fill our seas today.

In describing Thrissops ettlingensis and Thrissops kimmeridgensis, Dr. Ebert has not just named two new species — he has reopened a chapter of Earth’s history, one written in limestone and clay, and read in the delicate bones of creatures that swam when dinosaurs ruled the land and strange reptiles patrolled the skies.

More information: Martin Ebert, New species of the genus Thrissops (Teleostei, Ichthyodectiformes) in the Upper Jurassic of the Solnhofen-Archipelago (Germany) and Kimmeridge Clay (England), Zitteliana (2025). DOI: 10.3897/zitteliana.99.159055