The story of how paleontologists uncovered ancient evidence of butterflies and moths from nearly 236 million years ago reads like something straight out of a scientific adventure novel. But this is not fiction—it’s real history being unearthed in the deserts of Argentina. In a groundbreaking study published in the Journal of South American Earth Sciences, a team of paleontologists has uncovered the first evidence of lepidopterans (butterflies and moths) in the form of tiny scales preserved in ancient dung samples. These dung samples, which date back to the Triassic period, offer a glimpse into a period of life on Earth that was previously thought to lack these familiar, winged creatures.

The discovery was made at a dig site located in Talampaya National Park, Argentina—a place that has long been a treasure trove for paleontologists seeking to unravel the mysteries of ancient ecosystems. In this article, we explore this fascinating discovery, its implications for our understanding of the evolution of butterflies and moths, and what it tells us about the environment of the Triassic period, a pivotal time in Earth’s history.

The Discovery: Unearthing Ancient Dung

The story of this remarkable discovery began back in 2011 when excavation work began at a site in Talampaya National Park. The team, consisting of researchers from various Argentine institutions along with a colleague from the United Kingdom, had come to study ancient ecosystems preserved in the fossil record. What they found was not just the fossilized remains of dinosaurs or ancient plants, but the remnants of something much smaller, yet equally significant: ancient dung.

The site turned out to be a communal latrine used by a variety of animals in the Triassic period, including large herbivores. The presence of such a latrine, where many animals repeatedly urinated or defecated over an extended period, provided an invaluable opportunity for the researchers. Not only did it give them a direct window into the diets and behaviors of these animals, but it also offered an unexpected bonus: preserved scales from lepidopterans.

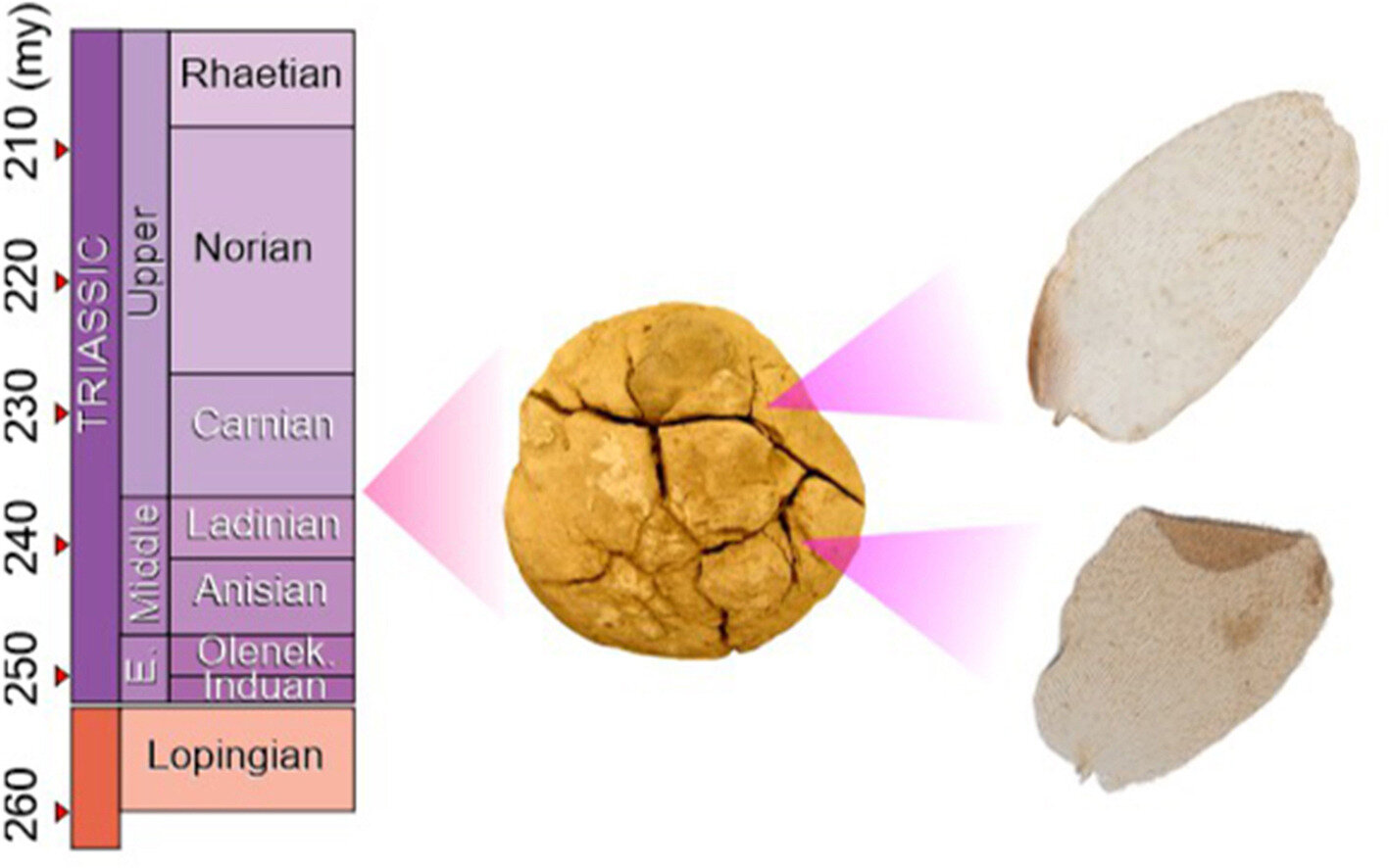

Once the dung samples were collected, they were sent to Argentina’s Regional Center for Scientific Research and Technology Transfer of La Rioja. There, the samples underwent detailed analysis, and what the team discovered stunned them. The dung, after all, was not just old—it was ancient. Radiometric dating placed the dung samples at approximately 236 million years old, placing them squarely in the heart of the Triassic period, roughly 16 million years after the end-Permian extinction event. This was a time when life on Earth was still recovering from one of the most catastrophic extinctions in history, a period when biodiversity was slowly starting to rebound.

Among the many fascinating findings was the unexpected discovery of tiny scales embedded in the dung. At first glance, these scales seemed insignificant, but a closer look revealed something much more remarkable: they were the scales of a lepidopteran—either a moth or a butterfly.

Filling the Gap in Lepidopteran Evolution

For paleontologists, this discovery was not just interesting in its own right, but it also had significant implications for the evolutionary history of one of the most iconic groups of insects: butterflies and moths. While research had already suggested that Lepidoptera first evolved around 241 million years ago, evidence of their existence in the fossil record had been frustratingly sparse. Physical evidence of lepidopterans, such as fossilized scales or wings, only appeared about 201 million years ago—leaving a gap of approximately 40 million years.

This new discovery of lepidopteran scales in dung from the Triassic period could help fill in that missing gap in the fossil record. It provides physical evidence that moths and butterflies were, in fact, present much earlier than previously thought. This is a crucial finding because it extends the known range of Lepidoptera back into the mid-Triassic, offering new insights into the early evolution of these fascinating insects.

But it wasn’t just the fact that lepidopterans were present during the Triassic that made this discovery so groundbreaking—it was also what the scales revealed about the early forms of these insects. The researchers tentatively identified the lepidopteran species in question as Ampatiri eloisae, a name given to the species in honor of the discovery and its implications for the study of ancient insects.

Ampatiri eloisae: A New Species for a New Era

The discovery of Ampatiri eloisae is a notable one for several reasons. First and foremost, it represents the identification of a new species of ancient lepidopteran, one that existed long before the familiar butterflies and moths we know today. Its discovery fills an important gap in the evolutionary timeline of the group, providing further evidence that lepidopterans were already diversifying during the Triassic period.

Based on the timescale, the researchers suggest that Ampatiri eloisae likely belonged to a subgroup of lepidopterans known as Glossata. This group includes modern butterflies and moths that possess a proboscis, a long, coiled feeding tube used to extract nectar and other nutrients. This is significant because it suggests that, like modern moths and butterflies, A. eloisae would have had a specialized mouthpart that allowed it to feed on sugary substances.

However, this raises an intriguing question: if flowers did not yet exist during the Triassic period, what did Ampatiri eloisae feed on? The answer lies in the type of plants that dominated the landscape at the time. While flowering plants had yet to evolve, conifers and cycads—two plant groups that were abundant during the Triassic—produced sugary droplets as a byproduct of their metabolic processes. A. eloisae likely fed on these sugary droplets, much like modern moths that feed on tree sap, fruit juices, or nectar from non-flowering plants.

This diet may have influenced the early evolution of lepidopterans, shaping their feeding mechanisms and their relationship with the plant life around them. The fact that lepidopterans were already feeding on plant-produced sugary droplets during the Triassic period suggests that the foundations for the complex ecological relationships between pollinators and plants were already being laid down millions of years before the rise of flowering plants.

The Importance of Dung Fossils in Paleontology

One of the most fascinating aspects of this discovery is the role that ancient dung—also known as coprolites—played in uncovering these lepidopteran scales. While fossils of animals, plants, and even insects are often studied by paleontologists, dung can provide an unparalleled snapshot of an ancient ecosystem. Dung samples preserve not only the remains of the animals that produced them but also the small bits of organic material they consumed or came into contact with during their lifetime. In this case, the dung preserved the scales of Ampatiri eloisae, offering a direct connection between the ancient insects and the ecosystem of the Triassic.

The study of dung fossils, therefore, is a crucial tool in understanding past ecosystems. Coprolites can provide valuable clues about diet, behavior, and environmental conditions, and they can sometimes preserve unexpected remnants—such as the scales of ancient moths and butterflies—that would otherwise be lost to time.

Implications for the Evolution of Pollinators and Plant Relationships

The discovery of Ampatiri eloisae also has broader implications for our understanding of the evolution of pollination and plant-pollinator relationships. Although flowering plants had not yet evolved during the Triassic, this discovery suggests that early forms of pollination may have been occurring in some form. By feeding on sugary droplets produced by conifers and cycads, A. eloisae may have played a role in the early stages of pollination, setting the stage for the later co-evolution of flowering plants and their insect pollinators.

The relationship between plants and pollinators is a central theme in the history of life on Earth. Today, we see a complex network of interactions between plants and insects, where insects like butterflies, moths, and bees are essential for the reproduction of many plant species. The early presence of lepidopterans in the Triassic suggests that the evolutionary roots of these crucial ecological relationships go back much further than previously thought.

Conclusion: A Glimpse into the Past

The discovery of Ampatiri eloisae and its lepidopteran scales in ancient dung from Talampaya National Park represents a significant leap forward in our understanding of insect evolution. It not only provides valuable new information about the early history of butterflies and moths but also offers insights into the ecosystems of the Triassic period—a time when life on Earth was still recovering from the cataclysmic end-Permian extinction.

As paleontologists continue to study the ancient past through the lens of dung fossils and other preserved remains, we are sure to uncover even more surprising and enlightening discoveries. The discovery of ancient lepidopterans reminds us that life on Earth is far older and more intricate than we often realize, and it deepens our understanding of the interconnectedness of all living things. In the end, the past is not just a story of extinction and loss; it is a story of adaptation, survival, and the gradual emergence of the vibrant world we know today.

Reference: Lucas E. Fiorelli et al, Back to the poop: the oldest hexapod scales discovered within a Triassic coprolite from Argentina, Journal of South American Earth Sciences (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.jsames.2025.105584