Ants are everywhere—under our feet, in our gardens, hidden inside cracks in the pavement. Though we rarely notice them beyond their endless trails to food scraps, ants are among the most successful creatures on Earth. Their strength lies not in size or ferocity but in their ability to cooperate. Colonies function like living cities, with worker ants carrying out the endless tasks that keep the society alive: foraging, tending eggs, building nests, and defending against invaders.

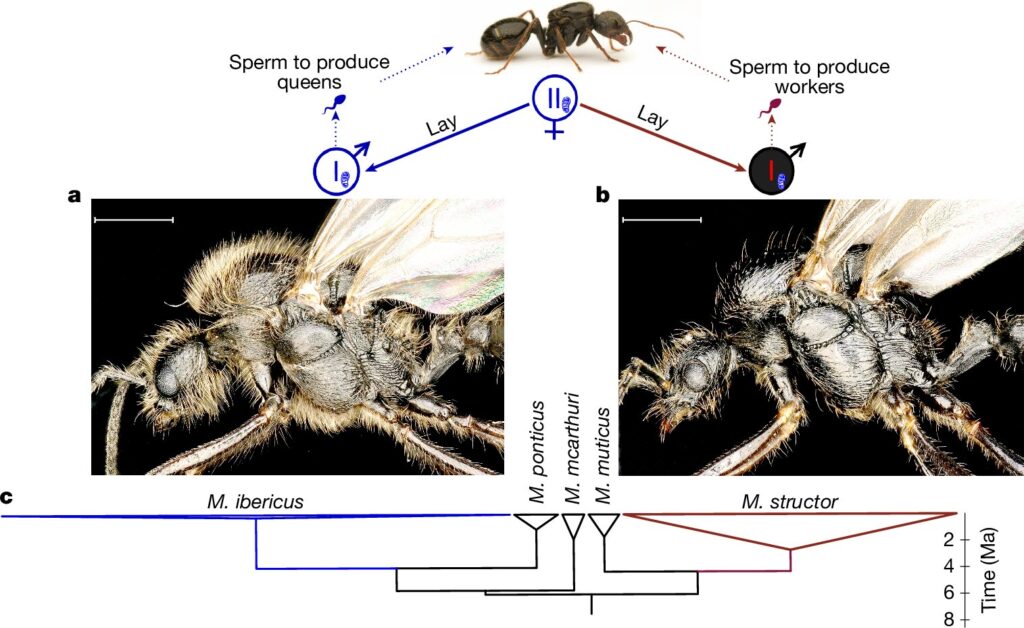

Without workers, there is no colony. Yet in some species of ants, an extraordinary problem arises. Their queens cannot produce workers on their own. When they mate with males of their own kind, the eggs develop into more queens, and unfertilized eggs become winged males—future suitors that leave to find mates elsewhere. That begs a fascinating question: if queens can’t make workers from their own species, where do the workers come from?

The answer leads us into one of the strangest reproductive strategies in the natural world.

Borrowing Genes from a Neighbor

For many such ants, the solution is hybridization. These queens mate with males from other, closely related species. The result is hybrid offspring that take on the role of workers. In this way, the colony gets the workforce it needs to survive, even though the arrangement may sound bizarre to human ears. Few animals rely so directly on mixing their lineage with another species just to function.

But as strange as this may seem, one particular species of ant, the Iberian harvester ant (Messor ibericus), takes the concept even further. Instead of simply mating with another species, it has evolved a way to clone another species’ males inside its own colony.

This discovery, recently described in Nature, reveals an evolutionary twist that challenges our very definitions of reproduction, species, and individuality.

A Mystery in the Soil

The story begins with field research across Europe. Scientists collected and analyzed 390 ants from five different Messor species. When they looked at the DNA of Messor ibericus colonies, the results were startling. Every worker they examined turned out to be a first-generation hybrid between M. ibericus and another species, Messor structor.

That would have been odd enough, but the mystery deepened. Many of these hybrid workers were found in places where no M. structor colonies existed at all. Even more puzzling, on the Italian island of Sicily, researchers found hybrid workers more than a thousand kilometers away from the nearest known M. structor population. How could queens be producing hybrid offspring when the supposed fathers weren’t even around?

Something far stranger had to be happening.

The Revelation of the Laboratory

To uncover the truth, researchers brought colonies of M. ibericus into the laboratory. In controlled conditions, they observed queens laying eggs, workers developing, and colonies thriving. The expectation was that without access to M. structor males, no hybrids could form. Yet hybrid workers continued to appear.

The conclusion was astonishing. M. ibericus queens weren’t finding M. structor mates in secret. They were cloning them.

Stored sperm inside the queens carried the nuclear DNA of M. structor, while the queens themselves contributed mitochondrial DNA of M. ibericus. The result was that male ants with M. structor nuclear genes but M. ibericus mitochondrial heritage were being born inside the colony. These cloned males then mated with the queens to produce hybrid workers. In essence, the queens had found a way to keep a miniature, self-sustaining lineage of another species living inside their colonies.

Xenoparity: A New Kind of Reproduction

The researchers coined a new term for this reproductive strategy: xenoparity, which means “foreign birthing.” Unlike any other known reproductive system in ants, xenoparity requires queens to generate members of another species in order to function.

This is not a small adjustment in the story of evolution—it is a radical departure from how we usually think about species. Typically, the ability to reproduce within your own kind defines what it means to be a species. But in M. ibericus, reproduction depends on keeping another species alive inside its genetic memory.

The origins of this strange arrangement likely lie in the evolutionary tug-of-war of “sperm parasitism,” in which one species comes to depend on another’s sperm for survival. Over time, M. ibericus appears to have lost the ability to produce workers independently, forcing it to develop this extraordinary cloning mechanism to keep colonies functioning.

What Does It Mean to Be a Species?

The discovery of xenoparity raises questions that ripple far beyond the world of ants. If a species depends on another species for its very survival—so much so that its queens clone another’s males—where do we draw the boundary of individuality? Is M. ibericus truly its own species, or is it part of a larger, two-species “superorganism,” as the authors of the study put it?

For centuries, scientists have wrestled with the definition of species, debating whether to define them by reproduction, genetics, or ecological roles. The Iberian harvester ant complicates this further. It blurs the line between self and other, between autonomy and dependency. Its colonies embody a partnership that is both parasitic and mutualistic, both exploitative and cooperative.

A Window into Evolution’s Creativity

Perhaps the most extraordinary lesson from Messor ibericus is that evolution does not follow simple rules. Life finds ways to solve problems, often in ways that defy our expectations. Worker ants are essential, so when nature blocked one path to producing them, evolution carved another—an almost unthinkable one.

In these ants, we glimpse evolution at its most inventive, rewriting the code of life not through the addition of new species but through the borrowing and repurposing of another’s genetic material. What appears bizarre to us is, for them, the only way forward.

The Beauty of the Strange

There is something deeply humbling in realizing that beneath the soil, tiny creatures are carrying out strategies of survival more complex and alien than anything we could dream up. Ants are often symbols of simplicity and tireless labor, but in truth, their societies are layered with mysteries that continue to surprise even the most seasoned biologists.

The story of the Iberian harvester ant reminds us that nature is stranger, wilder, and more inventive than we can imagine. It challenges our categories, our definitions, and our assumptions. And it leaves us with a profound truth: the boundaries of life are not fixed, but ever shifting, ever evolving.

In the end, perhaps the ants are teaching us something about ourselves. Just as they depend on relationships that blur the lines of individuality, so too do we exist only in connection—with one another, with the world, with the countless unseen systems that sustain us. The ants’ strange story is not just theirs—it is a mirror held up to the creativity of life itself.

More information: Y. Juvé et al, One mother for two species via obligate cross-species cloning in ants, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-025-09425-w

Jessica Purcell, Ant queens produce sons of two distinct species, Nature (2025). DOI: 10.1038/d41586-025-02524-8 , doi.org/10.1038/d41586-025-02524-8