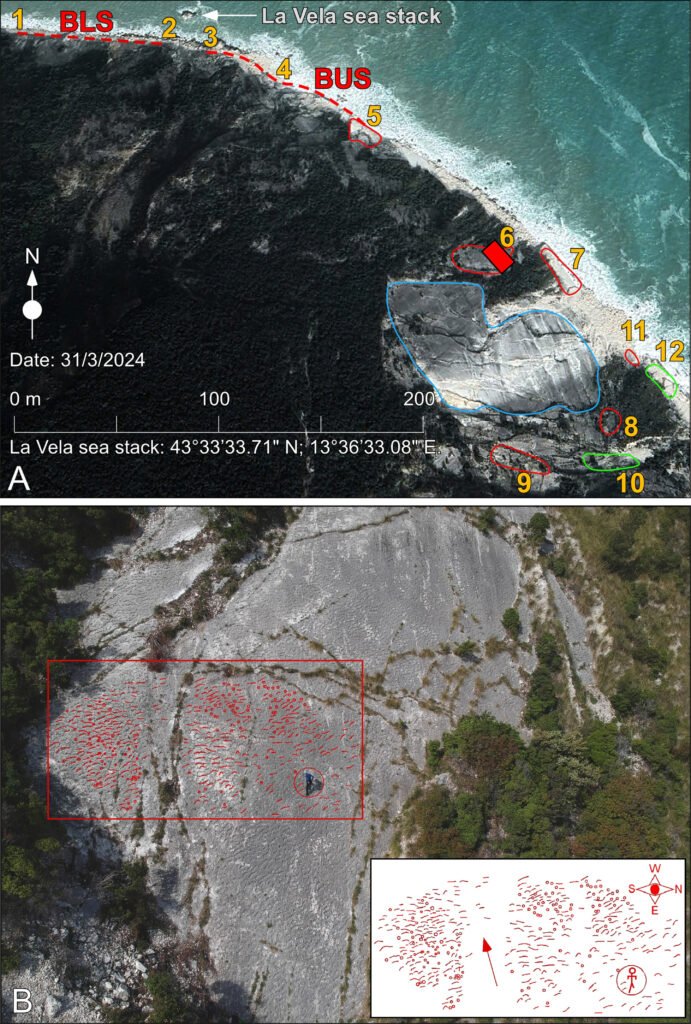

The story begins not in a laboratory but on a rugged slope above the Adriatic Sea, where a group of free climbers scaled the cliffs of Monte Conero in 2019. They were searching for challenge and adventure, not ancient secrets. Yet as sunlight cut across the pale limestone, they found themselves staring at something entirely unexpected. A vast rock slab, spread across two hundred square meters, was covered in markings that looked uncannily like the churned-up traces of a running herd.

One climber felt the strange pull of curiosity and later showed photos of the imprints to a geologist. That simple act—half accident, half instinct—set off a chain of events that would lead scientists deep into Earth’s Cretaceous past. The discovery has now taken shape in a formal study published in Cretaceous Research, but its origins remain wonderfully human: one moment of wonder, frozen on a mountainside.

The Moment the Past Stood Still

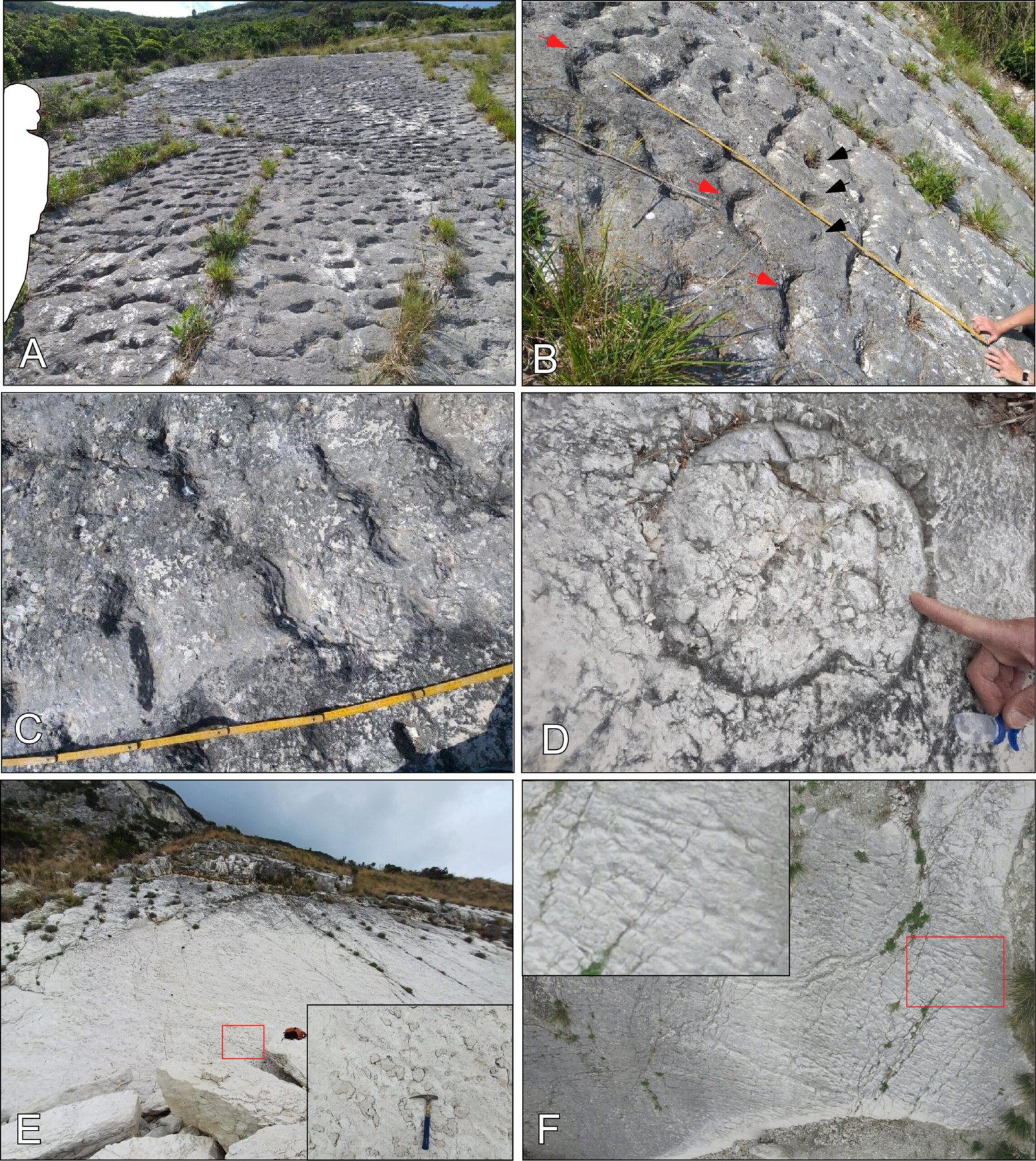

When scientists returned to Monte Conero, they found far more than scattered traces. More than 1,000 fossilized paddle-shaped footprints were embedded on the ancient seafloor, preserved in an astonishingly intact sheet of limestone. The tracks seemed to capture a single moment in time, like a snapshot left behind by creatures in mid-motion.

To understand what they were looking at, the researchers embarked on a meticulous reconstruction of the setting. They used stratigraphic logging to place the layer within its geological context, thin-section microscopy and microfossil analysis to study the sediments in detail, and magnetostratigraphy to align the rock’s magnetic properties with the global geologic record. Each technique added a brushstroke to a clearer and clearer picture.

Eventually, the scientists narrowed the scene to the lower Campanian stage of the Cretaceous period, roughly 83–80 million years ago. This was a time marked by increased seismic activity and sweeping environmental change. The team concluded that the event captured in the slab was no slow accumulation of tracks laid down over centuries. Instead, something dramatic had happened—a sudden chaos that left more than a thousand footprints behind.

According to the authors, “The footprints probably represent a stampede of panicking sea turtles that were mobilized en masse by an earthquake. These tracks were covered by a fluxoturbidite triggered by the same earthquake.”

An earthquake, a panicked rush across the seafloor, and then an immediate burial under cascading sediment. The moment the turtles fled was the same moment their tracks were sealed forever.

The Mystery of the Trackmakers

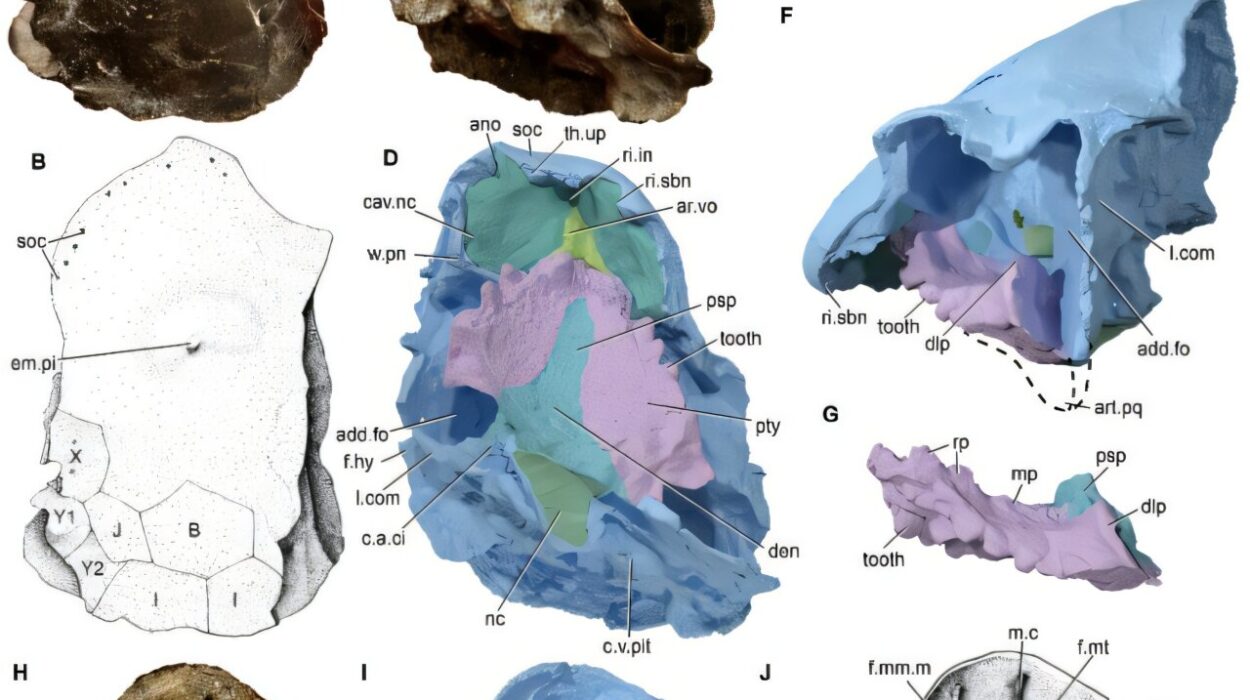

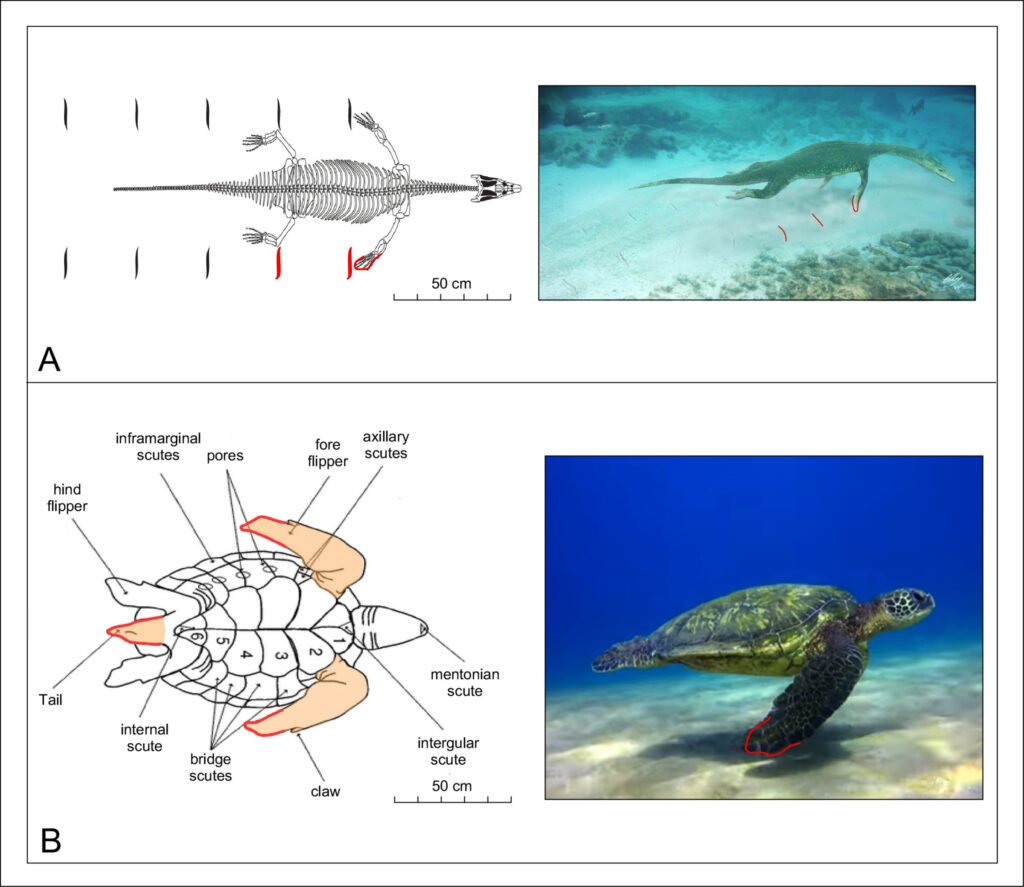

At first glance, the footprints looked like they belonged to some kind of large marine reptile. But which one. No fossils of sea turtles had ever been discovered in this region, which complicated the investigators’ task. The team laid out the possibilities by eliminating animals that could not have made the prints.

As the authors wrote, “Excluding fish, which do not use their fins to paddle on the seafloor, for our lowermost Campanian case of Monte Conero, we have to consider marine reptiles of three kinds: plesiosaurs (giant reptiles typically with a long neck and a small head), mosasaurs (i.e., large marine reptiles first found near the Meuse River, and sea turtles, specifically Protostegidae.”

Each of these animals possessed paddle-like limbs that could leave such imprints. Each existed during the Campanian stage. And each carried its own ecological habits and behaviors into the analysis.

Plesiosaurs, with their long necks and small heads, were not known for gathering in groups. Mosasaurs, powerful predators of the ancient seas, were generally solitary hunters. Sea turtles, however, offered another possibility. While usually solitary, some species are known to travel in large groups at specific times, especially during nesting or migration events.

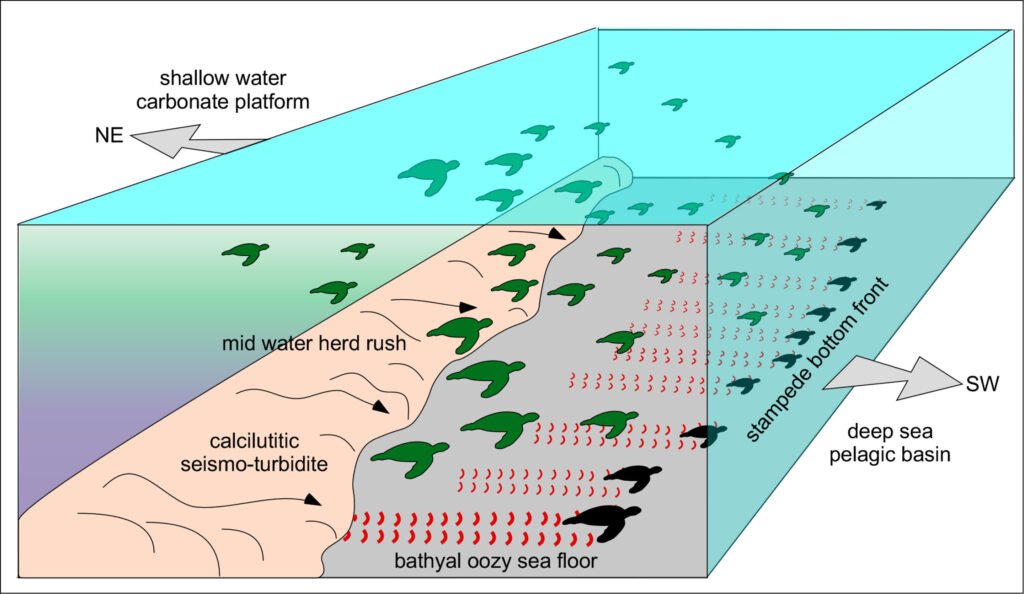

The more the researchers studied the tracks and the context of their formation, the more one idea rose above the rest. The imprints appeared to represent a mass movement—a coordinated rush rather than scattered individual wanderings. When combined with evidence of an ancient earthquake, the idea of a stampede became increasingly compelling.

Though the identification is not definitive, the weight of the evidence leans toward sea turtles—likely members of the extinct family Protostegidae—caught in a sudden race toward deeper, safer water. An entire group, moving together in fear, left their synchronized marks on the soft seafloor just moments before sediment buried their tracks forever.

A Window Into an Ancient Panic

With each new piece of evidence, the story of Monte Conero gained texture and emotion. This was not merely a collection of fossilized shapes. It was a scene. A moment of panic. A frantic surge of life responding to disaster.

The researchers imagine something like this.

A sudden quake shakes the seafloor. Sand and mud shift in a violent ripple. Light filters down through disturbed water. Startled marine reptiles—creatures that have survived countless dangers—feel the tremor and instinctively push off into motion. Their paddles strike the sediment in rapid succession, leaving clear, deep impressions.

Before the water calms, before the animals escape into deeper sea, a new wave of sediment flows over the scene. This fluxoturbidite, triggered by the same earthquake, sweeps downward like a blanket, sealing the story as it happens. The tracks stop abruptly, mid-flee. The moment becomes immortal.

Why This Discovery Matters

The slab at Monte Conero is more than a geological curiosity. It is a rare and vivid window into behavior—something exceptionally difficult to capture in fossils. Footprints show motion. They show decision. They show emotion, even if we must describe it cautiously: fear, urgency, collective instinct.

This discovery offers something that bone fossils alone cannot provide. It reveals how ancient animals responded to an environmental crisis. It hints at how earthquakes shaped life on the seafloor 80 million years ago. And it challenges scientists to rethink which creatures lived in this region and how they behaved under sudden stress.

Perhaps most exciting is what might still be hidden. The researchers acknowledge the uncertainty of the animals’ identity. Future fossils—another footprint layer, a bone, a shell—may someday complete the picture. For now, Monte Conero remains a place where science and mystery share the same slab of stone.

The discovery reminds us that the Earth’s past still waits in unexpected places. Sometimes it takes a trained scientist to find it. And sometimes it takes a free climber, pausing on a mountainside long enough to notice the echoes of a stampede frozen in rock.

More information: Paolo Sandroni et al, Reptile footprints on a pelagic seafloor as a vestige of a synsedimentary seismic event in the lower Campanian Scaglia Rossa basin of the Umbria-Marche Apennines (Italy), Cretaceous Research (2026). DOI: 10.1016/j.cretres.2025.106268