Picture a newborn Brachiosaurus no bigger than a golden retriever, nudging its way through prehistoric undergrowth with a dozen siblings at its side. These tiny herbivores sniff out plants, startle at every shadow and race away from predators eager for an easy meal. And all the while, their parents—towering more than 40 feet tall—graze somewhere dozens of miles away, not because they are uncaring, but because this is simply how dinosaur families worked.

That unsettling contrast is the starting point for new research by Thomas R. Holtz Jr., a principal lecturer in the University of Maryland’s Department of Geology. After decades of trying to imagine dinosaurs as living, breathing animals in their ancient worlds, Holtz has uncovered a surprising oversight in how scientists compare dinosaurs with modern mammals. His study, published in the Italian Journal of Geosciences, suggests that the key difference lies not in size or diet or even evolution, but in parenting.

“A lot of people think of dinosaurs as sort of the mammal equivalents in the Mesozoic era, since they’re both the dominant terrestrial animals of their respective time periods,” Holtz said. “But there’s a critical difference that scientists didn’t really consider when looking at how different their worlds are: reproductive and parenting strategies. How animals raise their young impacts the ecosystem around them, and this difference can help scientists reevaluate how we perceive ecological diversity.”

Where Caregivers and Wanderers Shape Entire Ecosystems

In the modern world, mammals raise children with what Holtz affectionately calls helicopter-level devotion. Young mammals, even large ones, live in the protective shadow of adults who hunt, forage and defend on their behalf. Holtz paints the picture with familiar examples. “You could say mammals have helicopter parents, and really, helicopter moms,” he explained. “A mother tiger still does all the hunting for cubs as large as she is. Young elephants, already among the biggest animals on the Serengeti at birth, continue to follow and rely on their moms for years. Humans are the same in that way; we take care of our babies until they’re adults.”

From the smallest rodent to the tallest giraffe, the pattern holds. Offspring share the same ecological niche as their parents because the adults do almost everything for them. They eat similar foods, travel the same paths and face similar dangers.

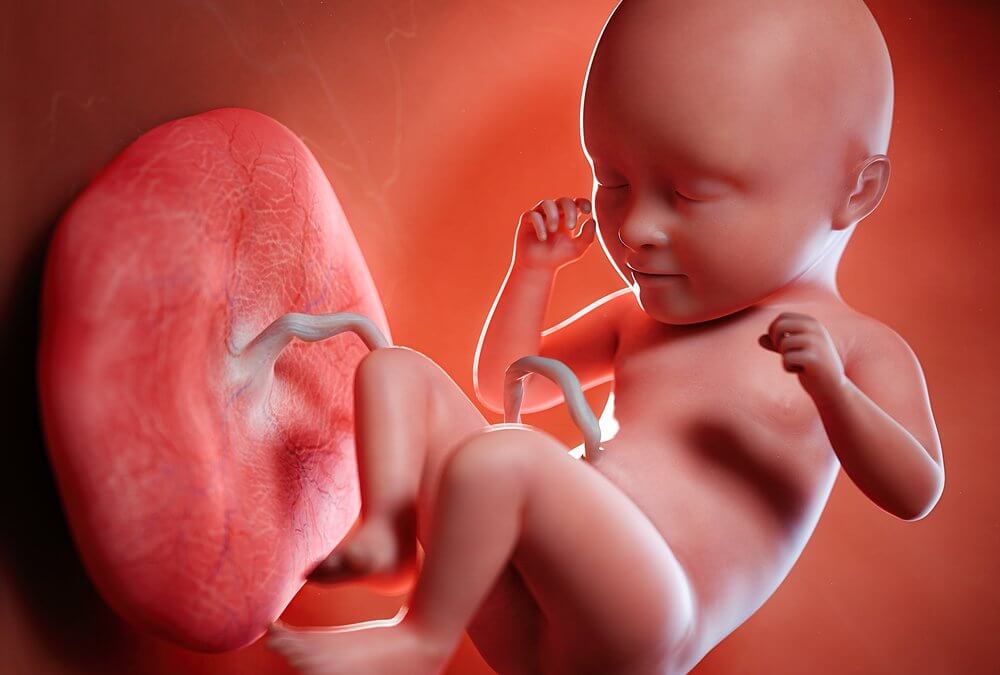

But dinosaurs played by rules that seem almost alien to us. Their offspring started life fragile and tiny, but they quickly stepped into independence. Within mere months—or at most a year—young dinosaurs parted ways with their parents. Their communities were not family groups but clusters of juveniles roughly the same age, wandering together like prehistoric schoolchildren roaming the neighborhood.

Holtz connects this to a similar modern pattern in crocodilians, some of the closest living analogs for dinosaurs. Crocodile parents fiercely guard their nests and protect hatchlings, but the support is short-lived. After a few months, the young disperse and fend for themselves for years before reaching full size.

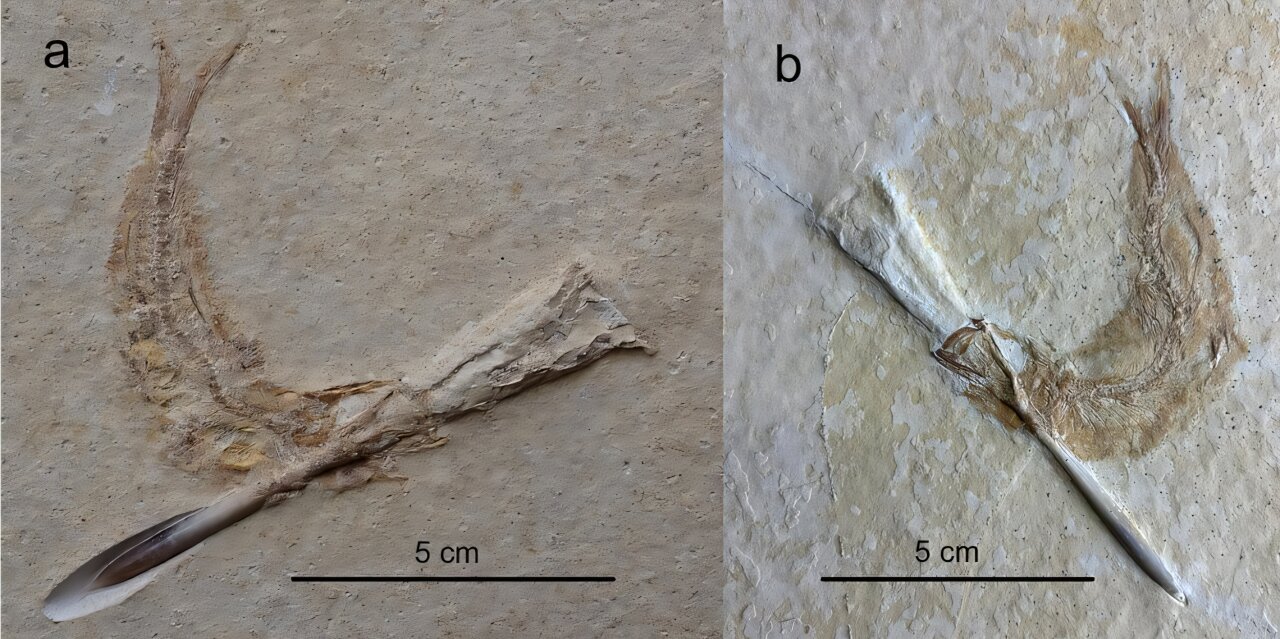

“Dinosaurs were more like latchkey kids,” Holtz said. “In terms of fossil evidence, we found pods of skeletons of youngsters all preserved together with no traces of adults nearby. These juveniles tended to travel together in groups of similarly aged individuals, getting their own food and fending for themselves.”

Dinosaurs laid eggs in large broods, and because they could reproduce frequently without investing years of parental care, their survival strategy depended on numbers rather than intensive protection. This early independence combined with dramatic changes in size over a lifetime created cascading effects in their environment.

How a Growing Dinosaur Becomes Many Species in One

Holtz argues that the life stages of a single dinosaur species were so dramatically different that juveniles and adults effectively acted like separate species in their environments. This wasn’t just a matter of size—it was a matter of ecological identity.

“The key point here is that this early separation between parent and offspring, and the size differences between these creatures, likely led to profound ecological consequences,” Holtz explained. “Over different life stages, what a dinosaur eats changes, what species can threaten it changes and where it can move effectively also changes. While adults and offspring are technically the same biological species, they occupy fundamentally different ecological niches. So, they can be considered different ‘functional species.’”

A juvenile Brachiosaurus the size of a sheep cannot lift its head ten meters into the air to browse the canopy the way an adult can. It must forage close to the ground, competing with entirely different animals. Predators that would never dare approach a full-grown giant might eagerly chase a young one. As the youngster grows—from something dog-sized to horse-sized to giraffe-sized—it steps through a continuously shifting series of ecological roles.

“What’s interesting here is that this completely changes how scientists view ecological diversity in that world,” Holtz said. “Scientists generally think that mammals today live in more diverse communities because we have more species living together. But if we count young dinosaurs as separate functional species from their parents and recalculate the numbers, the total number of functional species in these dinosaur fossil communities is actually greater on average than what we see in mammalian ones.”

In other words, dinosaur ecosystems may have been far richer and more complex than previously imagined—not because they had more biological species, but because each species behaved like several different species over the course of its life.

A Planet Built to Feed a Different Kind of Crowd

Holtz offers two possible explanations for how ancient ecosystems could sustain this layered tapestry of functional roles. First, the Mesozoic environment may simply have been more productive. Warmer temperatures and higher carbon dioxide levels would have fueled more plant growth, offering a deeper energy base to support more herbivores and the predators that hunted them.

Second, dinosaurs may have required less food than mammals of similar size, possibly due to lower metabolic rates. If true, the prehistoric world could support more large animals because they demanded fewer resources.

“Our world might actually be kind of starved in plant productivity compared to the dinosaurian one,” Holtz suggested. “A richer base of the food chain might have been able to support more functional diversity. And if dinosaurs had a less demanding physiology, their world would’ve been able to support a lot more dinosaur functional species than mammalian ones.”

Holtz emphasizes that these ideas do not necessarily mean dinosaur ecosystems were definitively more diverse than today’s mammalian world. Instead, he argues that diversity may take forms we have not been trained to recognize. By shifting the focus from biological species to functional species, the fossil record begins to reveal a more intricate story.

“We shouldn’t just think dinosaurs are mammals cloaked in scales and feathers,” Holtz said. “They’re distinctive creatures that we’re still looking to capture the full picture of.”

Why This Research Matters

Holtz’s work opens a new window onto the past, one that changes not only how we picture dinosaurs but how we understand ecosystems themselves. If a single dinosaur species can act like multiple functional species throughout its lifespan, scientists may need to revisit long-held assumptions about how prehistoric communities worked. This shift in perspective could reshape how researchers model food webs, predator-prey relationships and the evolution of entire ecosystems.

By recognizing that dinosaur worlds were shaped by free-ranging juveniles, rapidly shifting roles and layered ecological identities, we gain a deeper appreciation of the complexity of ancient life. And perhaps more importantly, we recognize that our own modern world is only one version of what an ecosystem can look like.

Holtz’s research reminds us of something profoundly humbling. The past is not just a simpler version of the present—it is a different world entirely, with its own rules, strategies and wonders still waiting to be understood.

More information: Thomas Holtz Jr., Bringing up baby: preliminary exploration of the effect of ontogenetic niche partitioning in dinosaurs versus long-term maternal care in mammals in their respective ecosystems, Italian Journal of Geosciences (2026). DOI: 10.3301/ijg.2026.09