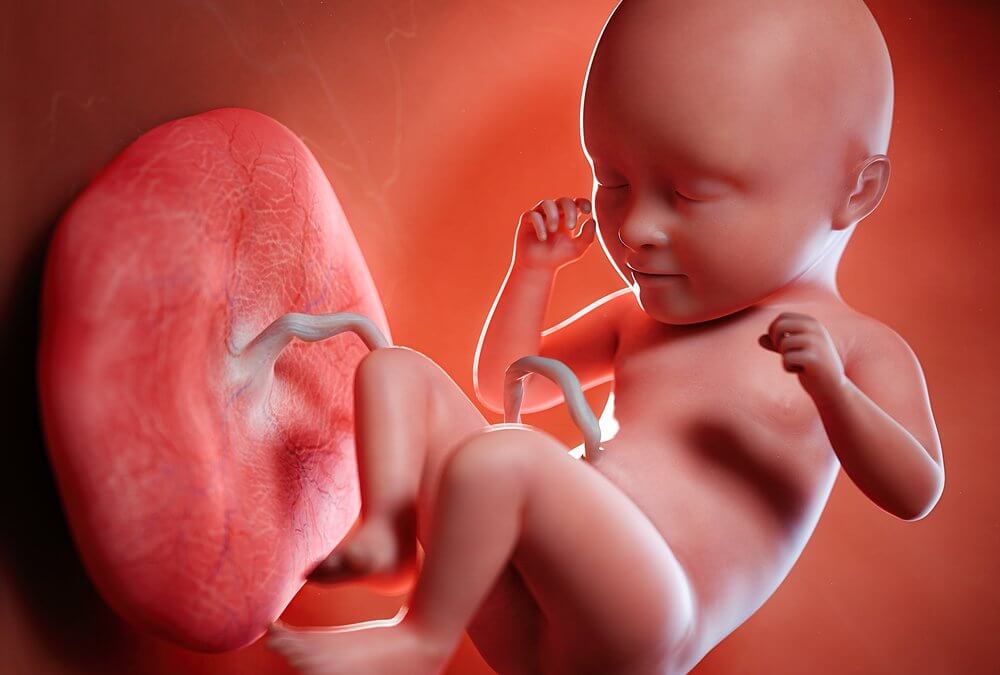

In the quiet chambers of pregnancy, where mother and fetus are tethered by a single lifeline, a secret evolutionary drama may have unfolded. According to a groundbreaking hypothesis proposed by researchers from the Universities of Cambridge and Oxford, it was here—in the womb, in the flow of hormones from the placenta—that the seeds of humanity’s greatest distinction were sown: our unusually large, social, and intelligent brains.

This new research, published in Evolutionary Anthropology, proposes a sweeping, biologically rooted story of how humans came to think, feel, and bond so differently from any other species. At its center is not just the brain itself, but the often-overlooked organ that sustains it before birth—the placenta.

“Our hypothesis puts pregnancy at the heart of our story as a species,” says Dr. Alex Tsompanidis, lead author and senior researcher at the Autism Research Center at the University of Cambridge. “The human brain is remarkable and unique, but it does not develop in a vacuum.”

Hormones in the Womb and the Blueprint of the Mind

It’s long been known that steroid hormones like testosterone and estrogen influence fetal brain development. But what if small variations in these prenatal hormones—regulated by the placenta—don’t just influence individual development, but actually helped steer the evolutionary trajectory of the entire human species?

Dr. Tsompanidis and his colleagues believe they do. Their new hypothesis connects subtle biological processes during gestation to sweeping patterns in human behavior and cognition. It also offers an intriguing potential explanation for why humans are so unlike our closest primate relatives.

“Small variations in the prenatal levels of steroid hormones can predict the rate of social and cognitive learning in infants,” says Tsompanidis. “They can even affect the likelihood of neurodevelopmental conditions such as autism. This prompted us to consider their relevance for human evolution.”

These insights build on decades of work linking prenatal sex steroid hormones to later cognitive development. Now, researchers are zooming out and asking a larger question: Could the way our placentas evolved—and the hormonal environment they created—be the missing link between biology and behavior, between womb and society?

The Brain That Grew for Company

What makes a human brain different isn’t just its size, but its connectivity. And one of the main drivers of that may be our profound need to connect.

“We’ve known for a long time that living in larger, more complex social groups is associated with increases in the size of the brain,” explains Professor Robin Dunbar, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Oxford and joint senior author of the study. “But we still don’t know what mechanisms may link these behavioral and physical adaptations in humans.”

Dunbar’s own work gave rise to the famous “Dunbar’s Number”—the estimated limit of stable social relationships a human can maintain, around 150. The more social complexity a species manages, the larger its neocortex tends to be. But correlation is not causation. Until now, there’s been little understanding of how the pressures of social life may have sculpted the human brain.

The new hypothesis proposes a causal pathway: higher estrogen levels during pregnancy, enabled by an increasingly efficient human placenta, may have increased neural connectivity in the fetus, fostering the cognitive flexibility and empathy needed for cooperative life in large groups.

Mini-Brains and a Hormonal Clue

The journey to this idea has been anything but speculative. It builds on recent experimental advances—particularly in the use of “mini-brains,” or cerebral organoids, created from human stem cells and grown in petri dishes.

These miniature models of the human brain allow researchers to study how hormones like testosterone and estrogen influence neural development. What they’re finding is striking.

Testosterone appears to boost brain volume, while estrogen seems to enhance the connectivity between neurons—creating stronger networks that may underpin complex thought and emotional regulation.

“This aligns with what we see in social species,” says Professor Simon Baron-Cohen, director of the Autism Research Center at the University of Cambridge and joint senior author on the paper. “Enhanced connectivity may have been key in enabling the social cognition that makes human societies possible.”

A Placental Advantage

The placenta, the life-support system that connects mother and baby, doesn’t just deliver oxygen and nutrients. It’s also a hormone factory. And recent research suggests that the human placenta may be unusually good at converting testosterone into estrogen, thanks to high levels of an enzyme called aromatase.

“The placenta regulates the duration of pregnancy and the supply of nutrients to the fetus, both of which are crucial for the development of our species’ characteristically large brains,” explains Professor Graham Burton, co-author and founding director of the Loke Center of Trophoblast Research at Cambridge. “But the advantage of human placentas over those of other primates has been less clear—until now.”

Compared to other primates, human pregnancies have been shown to have higher levels of estrogen. That subtle chemical edge may have driven not just the growth of larger brains, but the evolution of a more sociable, less aggressive species.

From Hormones to Human Nature

Prenatal sex steroid hormones are also essential for shaping sexual differentiation in the brain and body. Generally speaking, higher testosterone levels tend to promote traits associated with competitiveness and dominance, while estrogen supports nurturing and cooperative behaviors.

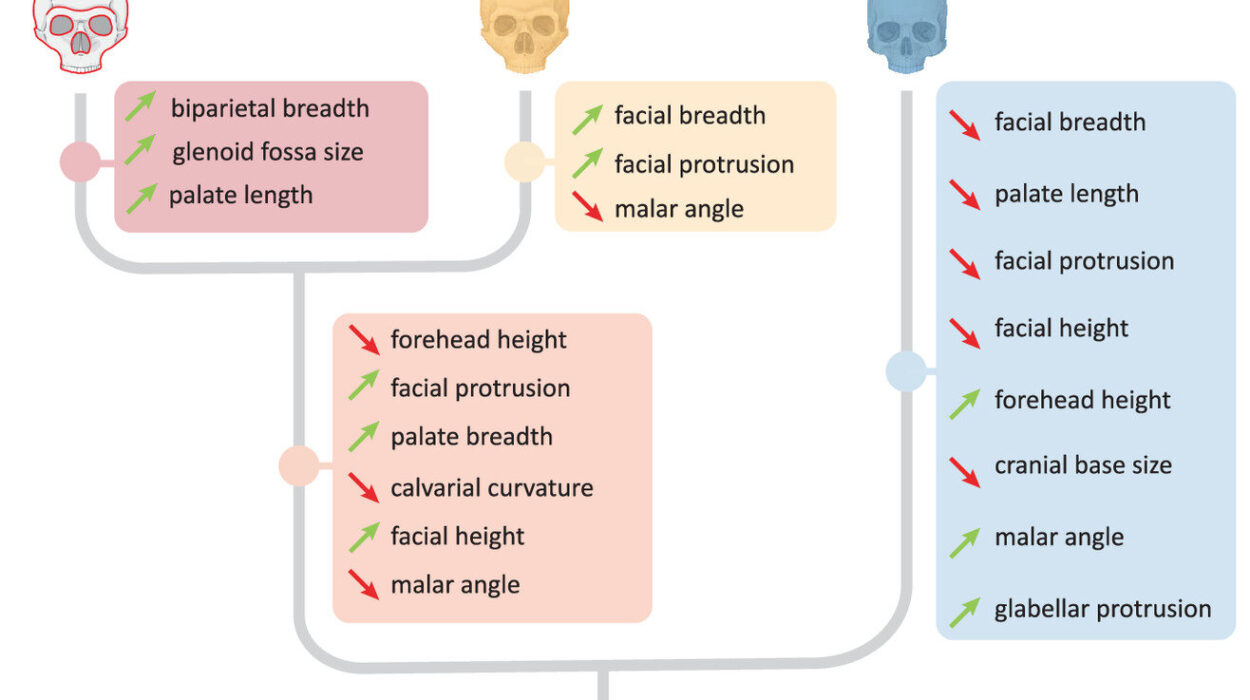

What’s fascinating is that, compared to other primates—and even to extinct relatives like Neanderthals—humans show a softening of those classic sex differences. In our species, traits linked to estrogen are more pronounced across the board, in both sexes.

This isn’t just seen in behavior. It’s etched into our anatomy—reduced body hair, smaller jaws, and even the length of our fingers. Researchers note a larger ratio between the second and fourth digits in humans, which correlates with estrogen exposure in the womb.

The implication is profound: evolution may have gradually turned down the dial on testosterone and dialed up estrogen in both males and females, subtly reshaping how we interact, empathize, and form communities.

Social Brains, Shared Futures

Humans are uniquely equipped to live in groups of unprecedented size. We gossip, joke, teach, console, collaborate. We invent languages, rules, and shared myths. None of this could exist without brains designed not just for intelligence—but for connection.

“A lower ratio of androgens to estrogens may have led to reductions in competition between males,” notes Dr. Tsompanidis. “At the same time, it could have improved fertility in females—together allowing humans to form larger, more cohesive social groups.”

This balancing act between biology and behavior may have given Homo sapiens the edge over Neanderthals, who had comparable brain sizes but smaller social networks and lower reproductive success. While Neanderthals vanished, humans expanded across the globe—cooperating, trading, and storytelling their way through history.

And it may have all started in the womb.

A Hypothesis That Rewrites the Origin Story

The authors are careful to call this a hypothesis, not a definitive explanation. Much more research is needed to test these ideas, particularly across different human populations and primate species. But the pieces are falling into place—from genetic evidence and endocrinology to anthropology and neuroscience.

This new lens places the placenta—often dismissed as a temporary organ—at the heart of human evolution. It recasts pregnancy not just as reproduction, but as the crucible of identity.

“This hypothesis builds on decades of studying how prenatal sex steroids affect neurodevelopment,” says Baron-Cohen. “It takes it further, suggesting these hormones may have also shaped the evolution of the human brain itself.”

If true, it would mean that the very traits that define us—our empathy, creativity, cooperation, and even our vulnerabilities—may trace back to a delicate hormonal dance before we ever drew breath.

The Womb as a Window into Human Destiny

Science rarely grants us neat origin stories. Evolution is a tangle of chance and necessity, of mutations and migrations. But every so often, a theory emerges that feels not only plausible, but poetic.

This one suggests that before we learned to walk, to speak, to dream, we were already becoming human—shaped not by the stars or the soil, but by a soft and silent chemical symphony within the womb.

The human brain is not just an accident of evolution, the authors argue. It is a consequence of deep maternal adaptation, of bodies learning to nurture brains not just to survive, but to understand each other.

And in that, perhaps, lies the most powerful story of all: that our capacity to connect began with the connection that made us.

Reference: The placental steroid hypothesis of human brain evolution, Evolutionary Anthropology Issues News and Reviews (2025). DOI: 10.1002/evan.70003