In the tangled story of invasive species, few lizards have left a trail as disruptive—and surprising—as the charismatic tegu. Native to South America and introduced to the United States through the exotic pet trade in the 1990s, tegus have become infamous in Florida, where their population boom has threatened native wildlife. But in a twist that reshapes everything scientists thought they knew, new research from the Florida Museum of Natural History has revealed that tegus are not newcomers at all. In fact, they have a deep-rooted prehistoric past in North America that stretches back millions of years.

A Fossil Hidden in Plain Sight

The extraordinary breakthrough began not in a jungle or a remote dig site, but in a storage drawer.

Jason Bourque, now a seasoned fossil preparator at the Florida Museum, was fresh out of graduate school in the early 2000s when he encountered a strange fossilized vertebra tucked away in the museum’s collection. The bone, just half an inch wide, was discovered in a fuller’s earth clay mine near the Florida-Georgia border. Though diminutive, the fossil carried with it a mystery that would take two decades to unravel.

“We have all these mystery boxes of fossil bones,” Bourque said. “I kept coming across this one vertebra and just couldn’t place it. Was it a lizard? A snake? It stayed in the back of my mind for years.”

The mine where it was found had been excavated rapidly, as it was set to close and be backfilled. Paleontologists had only a narrow window to gather as many fossils as possible from the site. That tiny vertebra was just one of many, left to gather dust—its identity lost to time.

Recognition at Last

Years later, while reviewing modern lizard vertebrae for a separate project, Bourque stumbled upon a photo of a tegu’s spinal bone. The resemblance was immediate—and electrifying.

“I saw the tegu, and I just knew right away—that’s what this fossil was,” he recalled.

But intuition alone wasn’t enough. A single vertebra is a slim basis for a definitive species identification. Paleontology traditionally depends on multiple skeletal features to verify such claims. Bourque needed a way to scientifically confirm his hunch.

AI Meets Paleontology

Enter Edward Stanley, the museum’s director of digital imaging. Stanley saw the mystery fossil as the perfect test subject for a new kind of identification technique—one that blended cutting-edge machine learning with advanced imaging.

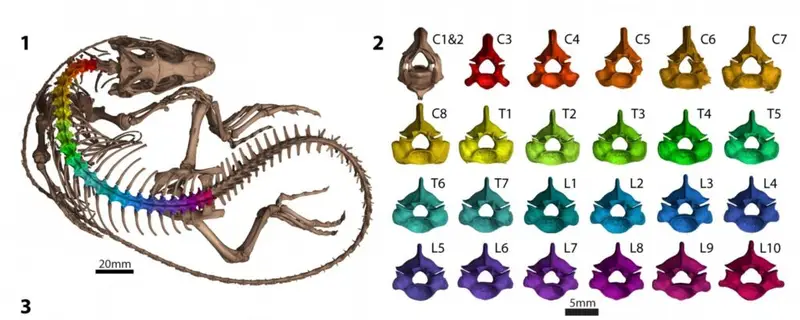

Using a CT scanner, Stanley created a high-resolution 3D model of the fossil and carefully mapped its key features—bumps, ridges, and curves—known as anatomical landmarks. The goal: compare this vertebra with a comprehensive library of others and see if any matched.

Luckily, the museum had access to an immense database through the openVertebrate (oVert) project, which hosts thousands of 3D vertebrate scans. Rather than laboriously comparing each vertebra manually, Stanley employed a groundbreaking algorithm created by Arthur Porto, the museum’s curator of artificial intelligence for natural history and biodiversity. This AI could automatically place anatomical landmarks on each scan, comparing more than 100 vertebrae with remarkable precision.

The result? A clear match with tegu vertebrae—confirming, beyond doubt, that the fossil belonged to a member of the tegu family.

A New Species Emerges

But the fossil didn’t just confirm ancient tegus once roamed North America. It unveiled something even more astonishing: this was a species previously unknown to science.

The fossil’s unique features didn’t match any existing tegu species in the museum’s databases. This meant it belonged to a now-extinct tegu, which the researchers named Wautaugategu formidus.

The name carries a poetic dual meaning. “Wautauga” is borrowed from a nearby forest and is believed to mean “land of the beyond,” a nod to both its prehistoric past and enigmatic nature. “Formidus,” Latin for “warm,” refers to the warm global climate during which this tegu likely lived—the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum.

The Miocene: A World Very Different from Today

Roughly 15 million years ago, the Earth was in the grip of one of its warmest intervals of the Cenozoic Era. Sea levels were much higher, and large swaths of modern-day Florida were underwater. The area near the fossil’s discovery would have been a coastal environment with lush vegetation and humid temperatures—ideal for reptiles.

Although tegus are land-dwelling lizards, they’re surprisingly adept swimmers. The team believes Wautaugategu formidus may have migrated from South America during this unusually warm period, perhaps using temporary land bridges or island-hopping across submerged terrain. But the region’s hospitality didn’t last.

A Brief Visit to Prehistoric Georgia

Evidence suggests this ancient tegu’s stay in North America was short-lived. As Earth’s climate cooled following the Miocene Climatic Optimum, the lizard likely faced an increasingly inhospitable environment. Reproduction is a temperature-sensitive process for egg-laying reptiles. Cooler temperatures may have interfered with egg incubation and population sustainability.

“We don’t have any record of these lizards before that event, and we don’t have any records after that event,” Bourque noted. “It seems they were here just for a blip.”

Still, that “blip” is enough to rewrite the story of tegus—and shed light on the broader history of reptile migration during global climate shifts.

Echoes in the Present: Invasive Tegus Today

While Wautaugategu formidus faded into extinction millions of years ago, its modern cousins are thriving in 21st-century Florida—though not without controversy. The current tegu invasion began in the 1990s, when pet enthusiasts imported the lizards for their striking appearance and calm demeanor. But as the reptiles grew—sometimes up to five feet long and ten pounds in weight—many owners released them into the wild.

Now, with a strong foothold in Florida’s ecosystems, tegus pose a major threat to native species, devouring everything from eggs to small mammals and competing with local predators. Conservationists are scrambling to contain their spread.

Ironically, while today’s tegus are viewed as ecological intruders, the fossil find suggests they may have a more ancient claim to the region than anyone imagined.

Future of Fossil Discovery

The implications of the study extend far beyond one vertebra. Stanley believes the fusion of AI and 3D modeling may revolutionize fossil identification.

“There are shelves and shelves of unsorted fossils in museums,” he said. “This is a first step toward automating the process. Instead of waiting years for experts to identify them one by one, we could do it in weeks.”

Such advancements could unlock hidden treasures within museum archives—long-forgotten bones awaiting rediscovery. The dream is a global, AI-powered fossil database that connects researchers around the world and speeds up our understanding of prehistoric life.

A Glimpse into Deep Time

The story of Wautaugategu formidus offers more than a quirky twist in Florida’s wildlife saga. It’s a reminder of how climate shapes life’s movements, and how today’s invaders may be echoes of ancient travelers. Through a combination of persistence, technology, and a bit of serendipity, a forgotten fossil has brought a long-lost species back into the light—and reopened a prehistoric chapter that was millions of years in the making.

As Bourque sets his sights on the Florida Panhandle in search of more fossils, one thing is clear: there’s still so much hidden beneath the surface—just waiting to be found.

Reference: Jason R. Bourque et al, A tegu-like lizard (Teiidae, Tupinambinae) from the Middle Miocene Climatic Optimum of the southeastern United States, Journal of Paleontology (2025). DOI: 10.1017/jpa.2024.89