For the first time in scientific history, a living tropical tree species—Dryobalanops rappa—has been discovered in fossil form. This groundbreaking discovery was made in Brunei, nestled within the lush rainforests of Borneo, one of the world’s most biodiverse regions. The fossils, believed to be over 2 million years old, represent not only the earliest known evidence of this species in the fossil record but also a vital key to understanding the evolution and resilience of Southeast Asia’s tropical ecosystems.

The discovery, led by researchers from Penn State in collaboration with the University of Brunei and international partners, was published on May 8 in the American Journal of Botany. It marks a major leap in tropical paleobotany and opens a new window into the deep-time story of Asia’s rainforests.

Fossil Clues From a Living Giant

The tree in question—Dryobalanops rappa, commonly known as Kapur Paya—is a towering member of the Dipterocarpaceae family, the ecological backbone of Southeast Asia’s rainforests. Still alive today but endangered, it thrives in the carbon-dense peat swamp forests of Borneo. Scientists have long known of its ecological role, but never before have they had concrete fossil evidence linking its modern form to ancient landscapes.

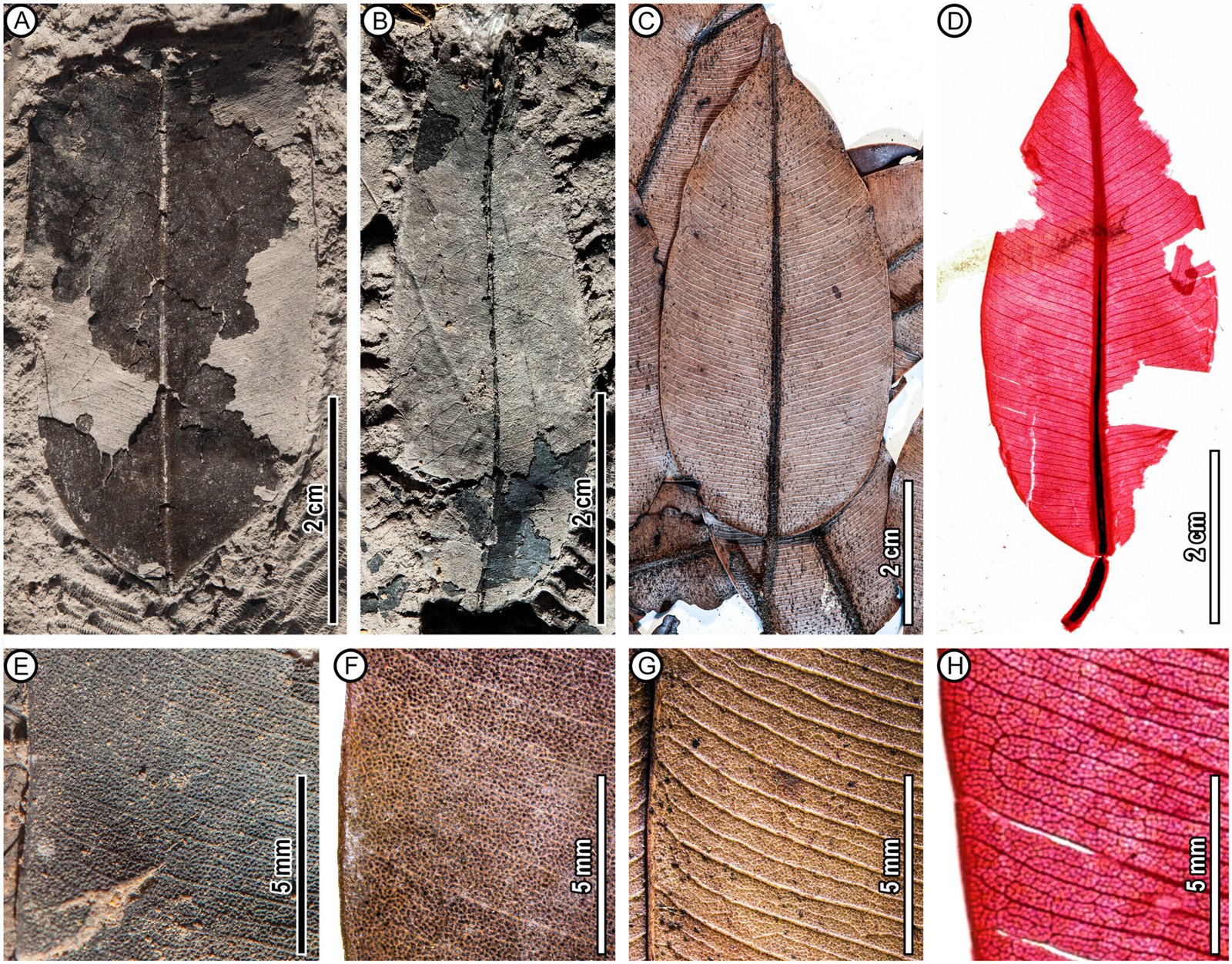

The research team identified the fossilized leaves by closely analyzing their cuticular microstructures—the waxy outer layer of leaves that can survive fossilization. To their amazement, the fossil leaf cuticles matched those of modern D. rappa with astonishing accuracy, even down to individual cellular arrangements. This was not merely a resemblance but a direct anatomical match, a botanical time capsule preserved in sediment for over two million years.

Filling the Gaps in Asia’s Botanical Record

“The fossil record of Asia’s wet tropical forests has been shockingly sparse, especially compared to the Amazon and Africa,” noted Dr. Peter Wilf, professor of geosciences at Penn State and senior co-author of the study. “That’s what makes this discovery so extraordinary. It bridges a glaring gap in our understanding of the region’s ecological history.”

While Africa and South America have yielded countless fossilized plant species over the decades, Asia’s fossil heritage has remained elusive. This new find changes that narrative, offering tangible proof that Dryobalanops rappa and, by extension, dipterocarp forests, have dominated Borneo’s rainforests for millions of years—an era-spanning testament to resilience and adaptability.

An Ancient Tree With a Modern Message

“This discovery provides a rare window into the ancient history of Asia’s wet tropical forests,” said Tengxiang Wang, a doctoral student at Penn State and the paper’s lead author. “We now know that this magnificent tree has been a dominant feature of the Borneo landscape since the Pleistocene or even earlier. That alone underscores its ecological importance.”

But Wang sees this as more than a scientific victory—it’s a call to action. “Conserving this tree and its habitat is not just about protecting today’s biodiversity,” he said. “It’s about safeguarding a living link to a deep evolutionary past. We are literally walking among giants from prehistory.”

The Dipterocarp Legacy: More Than Just Trees

Dipterocarps like Dryobalanops rappa are no ordinary trees. Often reaching over 70 meters in height, they form the towering canopies of Southeast Asia’s rainforests and serve as essential regulators of the climate. Their enormous trunks store massive amounts of carbon, making them pivotal players in the fight against climate change.

Moreover, these forests teem with life—orangutans, clouded leopards, hornbills, and countless species of insects and fungi depend on dipterocarps for food and shelter. When a dipterocarp falls, an entire microcosm collapses with it.

By proving that these trees have been integral parts of Borneo’s ecosystems for millions of years, the fossil discovery amplifies their conservation value. They are not just ecologically significant—they are historically irreplaceable.

Fossils as Tools for Conservation

In an era where species are disappearing faster than we can study them, the importance of fossil evidence cannot be overstated. “Our study shows how paleobotanical discoveries can strengthen conservation strategies,” said Wang. “By adding a historical lens to biodiversity, we shift the conservation narrative from preserving what’s left to protecting ancient survivors.”

In other words, this fossil isn’t just a piece of rock—it’s a storybook of resilience, etched in stone. It tells us that D. rappa has survived ice ages, tectonic shifts, and dramatic climate cycles. What it may not survive, however, is continued human destruction.

Facing the Threat: Deforestation and Habitat Loss

Despite their deep roots and ecological importance, dipterocarps face an existential threat. Southeast Asia’s forests are among the most rapidly disappearing on the planet, largely due to deforestation, palm oil plantations, and illegal logging. In places like Brunei, where peat swamp forests still harbor these ancient trees, conservation efforts are more urgent than ever.

“Peatlands are particularly vulnerable,” said Wilf. “They are often seen as wastelands, drained and burned to make way for development. But as our study shows, they are living archives of Earth’s botanical history. To destroy them is to erase a chapter of life on this planet.”

International Collaboration: A Model for the Future

The success of this study was rooted in global cooperation. The project brought together geoscientists, botanists, and conservationists from Penn State, the University of Brunei, and other institutions worldwide. It showcases what’s possible when scientific curiosity crosses borders and disciplines.

“This discovery is not the end—it’s a beginning,” said Wang. “We are now motivated to search for more fossils, not just in Brunei but across Southeast Asia. Who knows what other ancient giants are hiding beneath the forest floor?”

The Deeper Value of Trees

Beyond their ecological and historical roles, trees like Dryobalanops rappa possess a symbolic power. They remind us of time’s slow dance, of life’s persistence across epochs. To stand beneath a living kapur paya is to be dwarfed not just in height but in history.

In our fast-changing world, where we often measure time in seconds and trends, trees like this challenge us to think in millennia—to honor life that has weathered ages. Their survival is a kind of silent wisdom, and their potential loss would be a tragedy beyond words.

A Legacy Worth Protecting

In the end, the fossil discovery in Brunei is not just about one species—it’s about understanding our shared past and shaping a more conscious future. As scientists unearth more of these botanical time travelers, they do more than fill textbooks—they revive the memory of ancient forests and offer us a chance to protect their living descendants.

“By preserving these forests,” said Wilf, “we are not only saving species. We are preserving a story of life that stretches back millions of years—a story that still has chapters left to be written.”

And now, with fossil in hand and knowledge in heart, the world has one more reason to ensure those chapters are not lost.

Reference: Teng‐Xiang Wang et al, Fossils of an endangered, endemic, giant dipterocarp species open a historical portal into Borneo’s vanishing rainforests, American Journal of Botany (2025). DOI: 10.1002/ajb2.70036