The Grand Canyon is often called a book carved in stone—a place where the history of Earth reveals itself in vivid geological pages. Every layer, every cliff, every shard of rock tells a story older than human memory. But now, within this immense cathedral of time, scientists have uncovered a secret far deeper than any had expected. Hidden within its ancient walls are exquisitely preserved fossils from over half a billion years ago—tiny, soft-bodied creatures that once pulsed, scraped, and swam in warm Cambrian seas.

This is not just a discovery. It is an emotional and scientific awakening. For the first time, the Grand Canyon—one of Earth’s most iconic natural monuments—has yielded a window into a period that reshaped life itself: the Cambrian explosion, a moment in evolutionary history when life on Earth rapidly diversified and most major animal groups first appeared.

A Silent Revolution Preserved in Stone

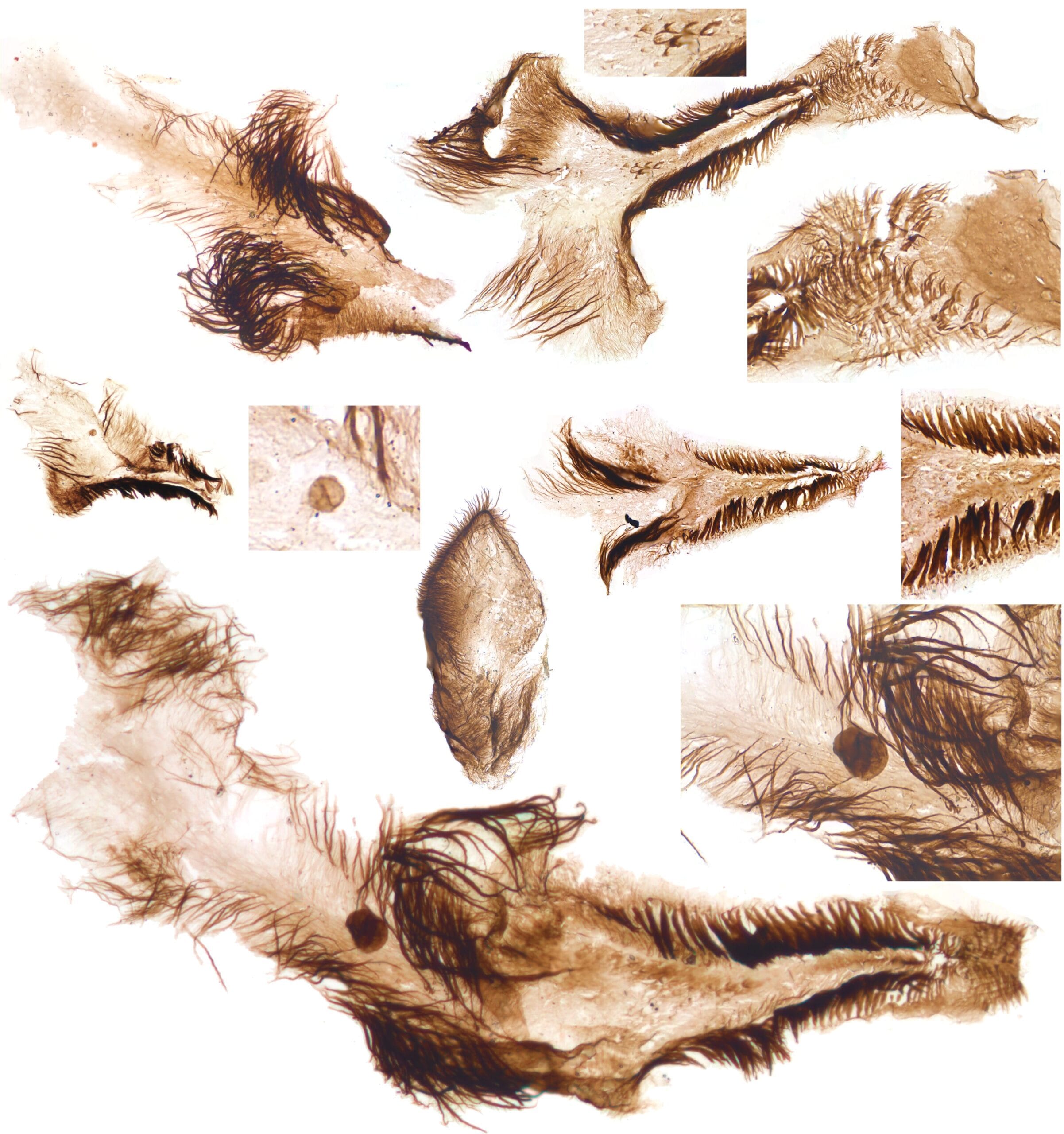

The fossils unearthed from the canyon don’t shout their presence. They are delicate, subtle, and often invisible to the naked eye. It was only through a meticulous process—dissolving small, fist-sized rocks in acid and examining the sediments under high-powered microscopes—that researchers, led by Cambridge University Ph.D. student Giovanni Mussini, were able to recover these lost lives.

The process is as fragile as the creatures it reveals. Soft-bodied fossils are notoriously rare. Their tissues usually vanish long before they can fossilize. But in certain special environments—oxygen-rich, nutrient-abundant, with fine-grained sediment capable of capturing minute detail—soft tissues can leave behind an echo of their original form. Until now, such preservation was thought limited to a few extraordinary sites: the Burgess Shale in Canada, the Maotianshan Shales in China. But now, the Grand Canyon joins this elite geological gallery.

The fossils themselves date back to between 507 and 502 million years ago, a slice of time when Earth was bursting with evolutionary ambition. Life had begun its great diversification, experimenting with form, function, and complexity. Every jaw, limb, and sensory organ we know today had its roots in this audacious biological symphony.

An Evolutionary “Goldilocks Zone” in the Heart of the Canyon

What makes this discovery even more striking is where it happened. Most Cambrian soft-bodied fossils have been found in environments poor in oxygen and resources—anoxic basins that ironically preserved fragile tissues by limiting decay. But such environments were unlikely to host the evolutionary fireworks that characterized the Cambrian explosion. They preserved life’s outlines, but not its fullest moments.

The Grand Canyon fossils change that narrative. These ancient animals lived in what scientists call an evolutionary “Goldilocks zone”—not too deep, not too shallow, rich in oxygen, and loaded with nutrients. During the Cambrian, the Grand Canyon region was much closer to the equator than it is today. Warm, shallow, sunlit seas bathed the area, fostering biodiversity on a spectacular scale. These were ecosystems humming with innovation, where survival meant staying ahead in an escalating evolutionary arms race.

Here, animals weren’t just surviving—they were thriving, experimenting, pushing boundaries. And now, in the fossilized remnants of their bodies and the sediments that surrounded them, we can see what they left behind.

The Ancient Engineers of Survival

The fossils that emerged from these ancient rocks may be tiny, but they speak volumes. Mussini and his team discovered a menagerie of early life—some familiar, some alien, all fascinating.

There were crustaceans with molar-like teeth, creatures that used bristled limbs like conveyor belts to sweep microscopic food into triangular grooves around their mouths. These weren’t crude feeders. They were refined machines—miniature marvels of evolutionary engineering, integrating multiple body parts into complex, high-efficiency feeding systems. In some samples, researchers could even see plankton-like particles nestled near their mouths, frozen in time like crumbs in ancient jaws.

Other finds included rock-scraping mollusks, reminiscent of today’s snails. Their ribbon-like tongues—radulas—were armed with microscopic teeth arranged in chains, used to graze algae or bacteria from surfaces. Though they scuttled across Cambrian rocks over 500 million years ago, their tools are shockingly familiar to anyone who has ever watched a garden snail feed on a leaf.

Yet among these ancient survivors was something stranger: a newly identified species of priapulid worm—a spiny, cylindrical creature whose nickname, the “penis worm,” often elicits a smirk. But Kraytdraco spectatus, as the team named it, is no joke. It possessed hundreds of finely branched teeth designed to filter food particles into a wide, extendable mouth. The name, inspired by the Krayt dragon of Star Wars lore, captures its bizarre yet majestic appearance—a nod to both science and imagination.

These animals didn’t merely exist. They were active agents in shaping their ecosystems, influencing the energy flow and nutrient cycles in these Cambrian seas. They dug, scraped, filtered, and burrowed, leaving behind not only their bodies but their movements—trails, burrows, feeding marks—etched into stone.

A Story Written in Shadows and Sediment

What makes this discovery truly emotional is not just what it tells us about life then, but what it reveals about life now. These tiny animals, almost invisible in their mineral husks, are ancestors—spiritual if not direct. Their feeding strategies, body plans, and even reproductive methods echo through time into modern forms. The way they explored their environment, took risks, competed, and innovated is the very same spirit that underlies every living thing on Earth today.

Mussini puts it elegantly: “There’s a lot we can learn from tiny animals burrowing in the sea floor 500 million years ago.” And he’s right. Evolution, like economics, thrives in abundance. In nutrient-rich environments, species invest in riskier, more complex innovations. When resources are scarce, the biological world tightens its belt, conserves energy, favors simplicity. In these Cambrian waters, evolution splurged.

It’s a lesson that resonates beyond biology. In times of abundance, we create. We reach for the stars. In times of scarcity, we hunker down. The fossil record of the Grand Canyon is not just a scientific archive. It’s a mirror held up to us.

The Canyon’s New Voice

The Grand Canyon, long admired for its towering cliffs and billion-year rock layers, now sings a softer, more intricate song. These fossils are not colossal skeletons or dramatic skulls. They are threads of silk woven into a much larger tapestry. Each tooth groove, each spiny leg, each digestive tract frozen in stone adds to our understanding of how life began to flourish in explosive, chaotic beauty.

The work is just beginning. The samples examined so far represent a tiny fraction of what likely lies hidden in the Grand Canyon’s shales. New expeditions will follow. More rocks will be cracked, more acids will bubble in laboratory beakers, more secrets will surface.

And each discovery will add another note to the symphony of early life.

From Cambrian Seas to Cosmic Questions

Ultimately, this discovery reminds us of something profound: the extraordinary resides in the overlooked. These creatures are small, but their legacy is enormous. They lived in a world without trees, without fish, without dinosaurs or mammals or birds. The continents were shifting, oxygen was spreading, and the rules of life were being written one organism at a time.

The fact that we can peer back through more than 500 million years of history and glimpse this biological experimentation, in such vivid detail, is almost spiritual. It speaks not just to the power of science but to the mystery of existence itself.

Who were these animals? What did they feel, sense, fear, want? They cannot answer us. But they leave a message in stone, a message that says: we were here. We lived. We tried.

And perhaps, so long as we continue to listen—to dissolve stone and sift truth through sieves of curiosity—we’ll keep finding them, long after the last canyon shadow fades.

Reference: Evolutionary escalation in an exceptionally preserved Cambrian biota from the Grand Canyon (Arizona, USA), Science Advances (2025). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adv6383