Along the rugged cliffs of England’s Jurassic Coast — a place where time itself seems carved into stone — paleontologists have uncovered a creature that bridges millions of years of evolutionary history. Its name is Xiphodracon goldencapensis, meaning “Sword Dragon of Golden Cap.” This newly identified species of ichthyosaur — a dolphin-sized marine reptile that ruled the oceans long before the dinosaurs vanished — is not just another fossil. It is a rare and almost miraculous window into a world that existed nearly 190 million years ago.

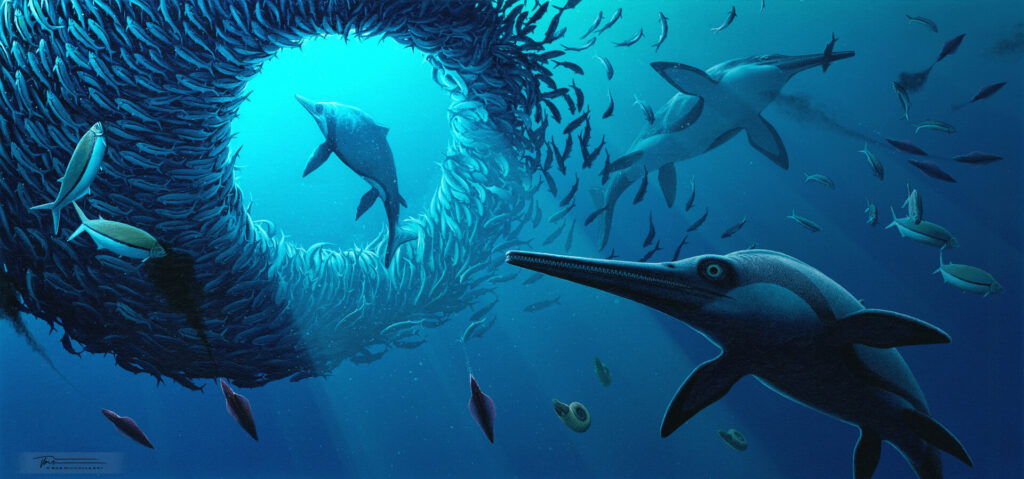

The fossil, found near Golden Cap in Dorset, is as breathtaking as it is scientifically important. Perfectly preserved in three dimensions, its skull reveals an enormous eye socket and a long, sword-like snout, the source of its evocative name. The creature stretched around three meters from snout to tail and would have glided through the Jurassic seas, hunting fish and squid in the dim blue light of ancient oceans.

For scientists, this discovery is more than an ancient curiosity. It fills a crucial gap in the ichthyosaur fossil record, revealing how these magnificent predators evolved during one of the most mysterious periods of their history — a time when old lineages disappeared and new ones emerged, reshaping the life of the prehistoric seas.

Rediscovering the Jurassic Coast’s Hidden Treasure

The Jurassic Coast has long been a treasure chest for paleontology. From the days of Mary Anning, the pioneering fossil hunter of the 19th century, its cliffs have yielded an astonishing array of ancient creatures. But the discovery of Xiphodracon goldencapensis stands apart — it is the first newly described genus of an Early Jurassic ichthyosaur from this region in over a century.

The fossil was first discovered in 2001 by Dorset fossil collector Chris Moore, who spotted the bones embedded in the cliffs near Golden Cap. Recognizing its potential importance, the specimen was carefully excavated and later acquired by the Royal Ontario Museum in Canada. There it remained, unstudied for years — a sleeping relic of deep time — until a team of scientists led by Dr. Dean Lomax of the University of Manchester and the University of Bristol began to investigate its secrets.

When Dr. Lomax first examined the fossil in 2016, he was struck by its unusual anatomy. “I knew it was something special,” he recalled, “but I didn’t realize how pivotal it would become in understanding a key moment in ichthyosaur evolution.”

The Missing Piece in an Evolutionary Puzzle

During the Early Jurassic, roughly 193 to 184 million years ago, the world’s oceans teemed with life — but it was also a time of great change. The Pliensbachian period, when Xiphodracon lived, witnessed a dramatic “faunal turnover”: older species of ichthyosaurs vanished, and entirely new families appeared. Yet the details of when and how this happened remained obscure. Fossils from this period are rare, leaving a frustrating gap in the evolutionary story.

Xiphodracon goldencapensis has changed that. Its anatomy places it between older ichthyosaur species and more advanced forms that would dominate later in the Jurassic. “It’s a kind of evolutionary bridge,” said Dr. Lomax. “We can now pinpoint the transition much earlier than we once thought. Xiphodracon is the missing piece of the ichthyosaur puzzle.”

Co-author Professor Judy Massare, an ichthyosaur expert from the State University of New York at Brockport, noted that ichthyosaur fossils before and after the Pliensbachian are abundant — yet none from within it show this unique combination of features. “Thousands of complete skeletons exist from the periods just before and after,” she said. “But none like this. It’s clear that something major happened to ichthyosaur diversity at this time — Xiphodracon helps us understand when that change began, even if we still don’t know why.”

A Glimpse of Life — and Death — in the Ancient Seas

What makes this fossil especially remarkable is not just its completeness, but the story it tells about the life — and death — of its owner. The skeleton preserves details so fine that scientists can infer both behavior and trauma.

According to Dr. Erin Maxwell, an ichthyosaur specialist from the State Museum of Natural History in Stuttgart, the bones show evidence of serious injury and disease. Some of the limb bones and teeth are malformed, suggesting the animal endured physical stress or infection during its lifetime. The skull also bears deep bite marks — likely inflicted by a much larger predator. “It was probably attacked by another ichthyosaur,” Dr. Maxwell explained. “Life in the Mesozoic seas was a dangerous prospect. Even top predators were not safe.”

The fossil even appears to preserve traces of the creature’s last meal — the faint remains of fish or squid near the stomach region. This offers a hauntingly intimate view of its final moments: a swift hunter ambushed by a larger rival, its meal unfinished, its body sinking slowly to the seafloor where it would be entombed for nearly 190 million years.

Anatomy of a Sea Dragon

Ichthyosaurs, often called “sea dragons”, were not dinosaurs but marine reptiles. They evolved from land-dwelling ancestors that returned to the water, adapting so perfectly that they came to resemble modern dolphins and sharks — examples of evolutionary convergence, where similar environments produce similar body plans.

Xiphodracon was no exception. Its streamlined body and powerful tail would have made it an agile swimmer, while its large eyes — some of the biggest relative to body size of any animal in history — allowed it to hunt in the dark depths. The elongated, sword-like snout that inspired its name was likely used to slash or snap up prey.

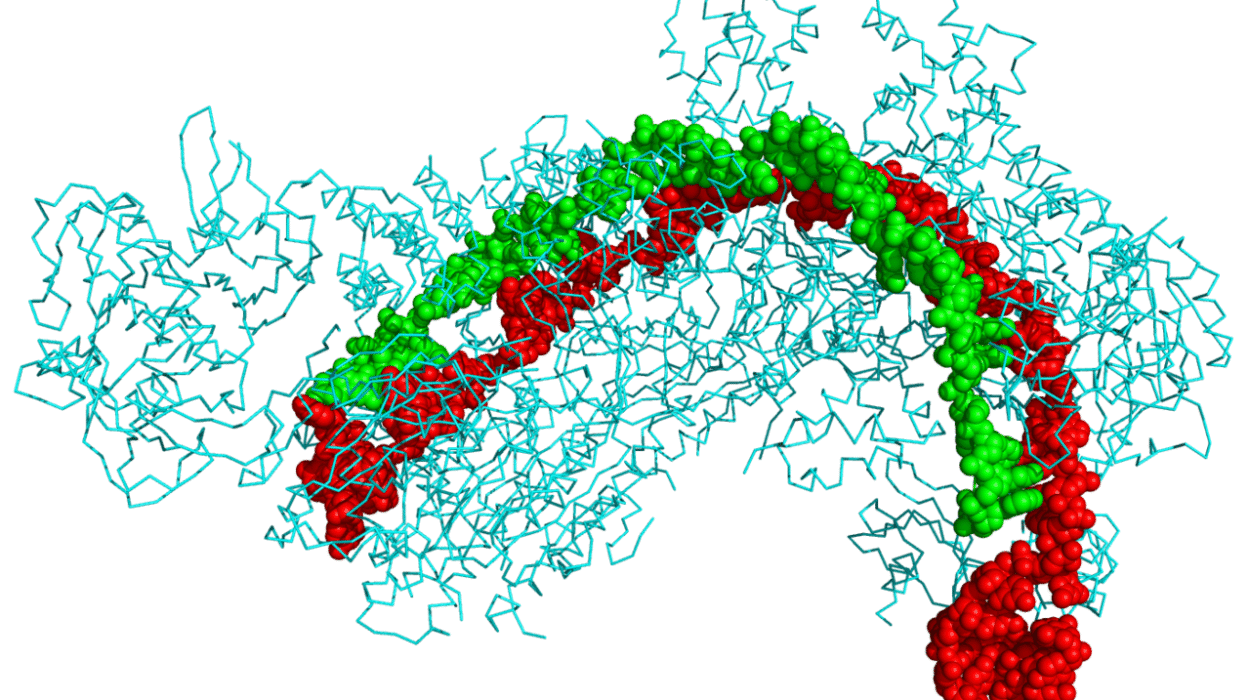

Yet, within its elegant design, paleontologists found something entirely new. Around its nostril was a peculiar bone structure — a lacrimal bone with strange prong-like extensions never before seen in any ichthyosaur. This feature, along with several subtle details of the skull and vertebrae, confirmed that the fossil represented not just a new species but a new genus entirely.

As Dr. Lomax put it, “One of the coolest things about discovering a new species is that you get to name it. We chose Xiphodracon because of its long sword-like snout — from the Greek xiphos for sword and dracon for dragon — a nod to the ichthyosaurs’ long-standing nickname as sea dragons.”

A Fossil Frozen in Time

What sets this specimen apart from most ichthyosaur fossils is its three-dimensional preservation. Many fossils along the Jurassic Coast are flattened by millions of years of pressure, but Xiphodracon’s bones retained their original shapes, offering scientists an unparalleled glimpse of the creature’s anatomy.

Such preservation is extremely rare — especially for ichthyosaurs from the Pliensbachian. In fact, it may be the most complete prehistoric reptile ever discovered from that period anywhere in the world. The fossil’s completeness makes it a benchmark specimen for future research into early ichthyosaur evolution.

Now housed at the Royal Ontario Museum in Toronto, the Sword Dragon of Dorset will soon be displayed to the public. Visitors will be able to look into the hollow eye socket of a creature that once swam through tropical seas where England now stands — a silent emissary from a vanished world.

A Window into Earth’s Ancient Past

Every fossil is a fragment of a much larger story — a record of transformation, survival, and extinction written in stone. Xiphodracon goldencapensis is a reminder of the fragility and resilience of life. Its discovery illuminates a period of evolutionary upheaval when nature was reinventing itself after mass extinctions, reshaping the oceans for the next chapter in Earth’s biological saga.

For paleontologists, this single fossil helps solve a scientific mystery. For the rest of us, it invites a more human reflection — that life, whether 190 million years ago or today, is a story of adaptation in the face of change, of beauty and struggle intertwined.

The Sword Dragon Lives On

As researchers continue to study Xiphodracon, they hope it will shed new light on how marine reptiles evolved to dominate the seas and how environmental changes shaped their fate. The fossil not only enriches our understanding of the past but also deepens our sense of connection to the living world.

We, too, are part of this same continuum of life — our bones and blood shaped by ancient oceans, our survival dependent on the same cycles of change that ruled the Jurassic seas. The Sword Dragon of Dorset, silent yet eloquent, tells us that even in extinction there is meaning — that through science, the lost can speak again.

In the stillness of the museum, when you stand before the curved snout and fossilized eye of Xiphodracon goldencapensis, you are not just looking at an ancient reptile. You are gazing into the memory of Earth itself — a memory carved in stone, whispering across the eons of time.

More information: A new long and narrow-snouted ichthyosaur illuminates a complex faunal turnover during an undersampled Early Jurassic (Pliensbachian) interval. Papers in Palaeontology. DOI: 10.1002/spp2.70038 onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/10.1002/spp2.70038