Long before the thundering hooves of cavalry shook battlefields, before cowboys rode across sunlit plains, and before horses became symbols of speed, strength, and loyalty, they were something quite different—something almost unrecognizable. Imagine a forest dense with tropical vegetation, humid and steaming in the warmth of the early Eocene, some 55 million years ago. Beneath the shadows of enormous ferns and towering trees, a small, dog-sized creature picks its way delicately through the underbrush. It is no horse in the modern sense. Its toes are spread for balance on soft, marshy ground. Its teeth are those of a browser, made for chewing leaves rather than grass. Yet in its nervous movements and alert eyes, there is something familiar.

This is Eohippus, the “dawn horse,” and though it is no more than 30 centimeters tall at the shoulder, it is the ancestor of today’s magnificent stallions and mares. The story of the horse is not one of a simple lineage marching through time, but a complex and dramatic journey—a grand evolutionary saga of change, adaptation, extinction, and survival. Over 55 million years, the horse has evolved in response to climate, predators, shifting landscapes, and the encroaching shadow of humankind. It is a tale etched in fossilized bones, ancient teeth, and the DNA that pulses beneath a modern mane.

Eohippus: Beginning in the Forests

The first chapter in the horse’s evolutionary history begins not on open plains, but in the dense subtropical forests of what is now North America. Here, during the early Eocene epoch, around 55 million years ago, Eohippus—also known scientifically as Hyracotherium—roamed the woodlands. It was an animal of modest proportions, no larger than a domestic cat or small dog. It had four toes on its front feet and three on its hind, each toe ending in a small hoof-like structure, soft enough for navigating through thick undergrowth.

Despite its name, Eohippus was not a horse in the modern sense, but a distant relative. Its body was built for darting through underbrush, and its teeth—low-crowned and suited to chewing tender leaves and fruit—betray a diet adapted to the forest environment. In a world dominated by large mammals and giant birds, this little creature survived through speed, agility, and the protection of the trees.

As the Eocene progressed, climate fluctuations began to reshape the landscape. Dense forests gave way to more open woodlands and grassy patches, challenging Eohippus and its descendants to adapt or disappear. This was the beginning of an evolutionary journey that would span continents and epochs.

A Branching Tree: The Rise of New Forms

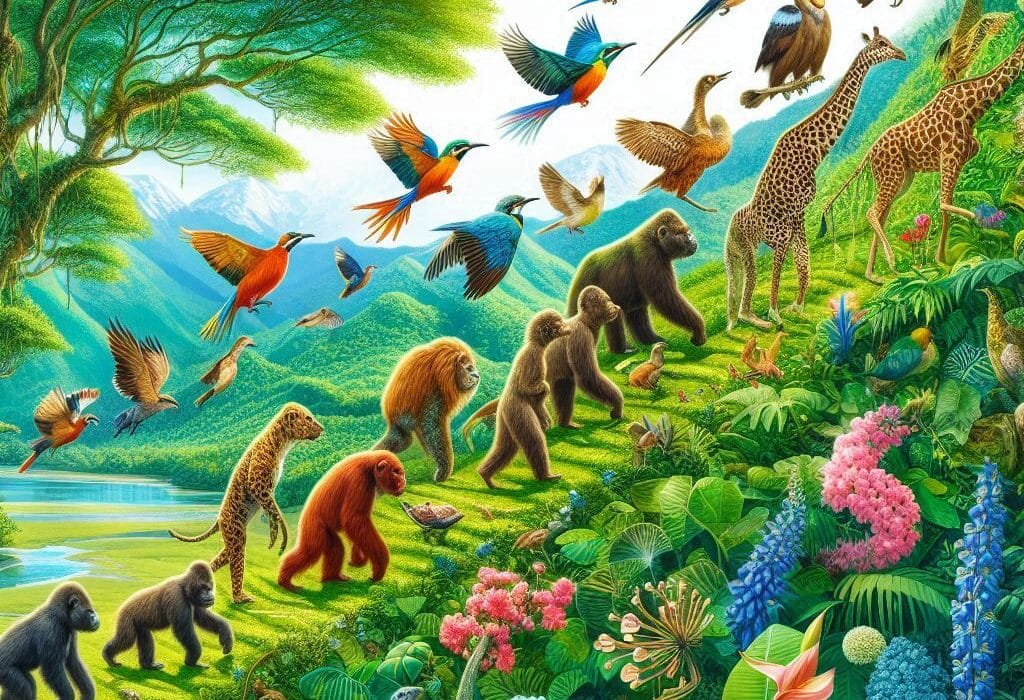

One of the most remarkable aspects of horse evolution is its branching nature. While popular depictions often suggest a straight line from Eohippus to Equus, the reality is much more complex. From the dawn horse evolved a series of genera, each adapting to different environments, many of which went extinct.

As the Eocene gave way to the Oligocene, some 34 million years ago, the descendants of Eohippus had evolved into animals such as Mesohippus—a larger, more advanced creature that stood around 60 centimeters tall. Mesohippus still bore three toes on each foot but was beginning to show signs of adaptation to more open terrain. Its limbs were longer, its brain slightly larger, and its teeth more developed, capable of grinding tougher vegetation. This marked the beginning of a shift from browsing to grazing, from forest to grassland.

In the Miocene epoch, around 20 million years ago, the landscape of North America continued to open up. Global cooling trends reduced forest cover, and vast savannahs spread across the continents. The horses responded dramatically. One of the most successful genera of this period was Merychippus, a fully three-toed grazer adapted to open grasslands. It was larger than its ancestors, with high-crowned teeth suited for grinding abrasive grasses—a revolutionary adaptation that allowed it to exploit new food sources.

The evolution of teeth in horses is one of the clearest examples of natural selection at work. As grasses became the dominant vegetation, horses developed more durable, ever-growing molars that could withstand the silica-rich blades and gritty soil often consumed along with the plants. This innovation would shape the future of the entire lineage.

The Birth of One Toe: Efficiency on the Plains

By the time the Pliocene epoch began, around 5 million years ago, the three-toed horses of the Miocene had given rise to forms that resembled the modern horse far more closely. The key innovation was in the feet. Gradually, the side toes diminished in size and utility, becoming vestigial. The middle toe—strong and elongated—became the dominant structure, culminating in a single hoof. This transformation provided several advantages. A single toe supported by a strong, springy ligament system allowed for more efficient locomotion over hard ground, increasing speed and endurance—essential for escaping predators on the open plains.

This evolutionary leap gave rise to the genus Equus, the group that includes all living horses, donkeys, and zebras. Fossil evidence suggests that Equus first appeared in North America around 4 to 5 million years ago. From there, these horses began to migrate. They crossed into Asia via the Bering land bridge and spread into Europe and Africa. Ironically, they vanished from their native North America around 10,000 years ago, possibly due to a combination of climate change and human hunting.

But before their extinction on the continent, horses had already taken root across the Old World, where their evolution continued under a new force—humanity.

Domestication: A Turning Point in Two Histories

Some 6,000 years ago, in the steppes of Central Asia, the destiny of horses changed forever. For most of their history, horses had been prey animals—hunted by saber-toothed cats, wolves, and, later, early humans. But somewhere on the Eurasian plains, human communities began to see horses not just as quarry, but as partners.

The domestication of the horse is one of the most profound events in human history. It transformed societies, economies, and empires. It allowed for the movement of people and ideas across vast distances, reshaped the art of war, and became deeply woven into mythology and identity.

Genetic and archaeological evidence points to the Botai culture in modern-day Kazakhstan as among the earliest horse domesticators, around 3500 BCE. At first, horses may have been kept for meat and milk, similar to cattle. But soon, humans learned to ride. This required more than just physical control; it required understanding the psychology of a prey animal. Early riders would have needed to gain the horse’s trust, to coax it rather than conquer it.

The benefits were enormous. Mounted humans could travel faster and farther, expand trade networks, and control herds of livestock more effectively. As chariots and cavalry developed, horses became instruments of military might. Civilizations that mastered the horse often dominated those that did not.

But domestication also reshaped the horse. Selective breeding favored traits such as strength, speed, endurance, and temperament. Different breeds emerged for different tasks—racing, plowing, carrying, and companionship. Over time, the wild form of Equus ferus, from which domestic horses descended, dwindled. Today, only one wild subspecies, Equus ferus przewalskii—Przewalski’s horse of Mongolia—survives, and even it has been touched by human intervention.

Diversity Within the Lineage

Modern horses are all members of Equus ferus caballus, the domestic horse. Yet within this single species lies an extraordinary range of variation. The smallest pony and the largest draft horse can trace their ancestry to the same stock, yet through human selection, they have been sculpted into forms suited for everything from warfare to children’s riding lessons.

This artificial selection mirrors natural evolution in some ways. Just as climate and diet once shaped ancient horses, human needs and preferences now shape modern breeds. Some, like the Arabian horse, are known for endurance and intelligence; others, like the Clydesdale, are bred for power and size. Yet all retain the core features of their ancestors: a single hoof, high-crowned molars, long limbs built for running, and a social, herd-oriented brain.

Even the zebra, with its striking black-and-white stripes, is a close cousin. Zebras belong to the same genus, Equus, and share a common ancestor with domestic horses from several million years ago. Though they have never been successfully domesticated, their behaviors, diets, and social structures offer insights into the ancestral traits of all horses.

Extinction and Return: The Horse in North America

One of the most fascinating chapters in the horse’s evolutionary history is its disappearance from its birthplace. Horses originated and flourished in North America for tens of millions of years, yet they vanished from the continent at the end of the Pleistocene epoch, around 10,000 years ago. The reasons remain debated. Climate change played a role, as did the arrival of human hunters. The great megafaunal extinction that wiped out mammoths, saber-toothed cats, and giant ground sloths also claimed North American horses.

For thousands of years, the Americas were horse-free. The peoples of these lands developed rich cultures without them—until the 15th and 16th centuries, when Spanish explorers reintroduced horses to the New World. These animals, descended from Eurasian stock, thrived in the wild. Escaped or abandoned horses formed feral populations, giving rise to the mustangs of the American West.

To Indigenous peoples, the horse was a revelation. In just a few generations, tribes like the Comanche and Lakota became master horsemen, transforming hunting, warfare, and mobility. The reintroduction of the horse was not just a return of an animal to its ancestral land—it was a cultural and ecological revolution.

Bones in the Earth: The Fossil Record as Witness

The evolution of the horse is one of the best-documented examples in the fossil record. From the tiny bones of Eohippus to the massive skeletons of Equus, scientists have uncovered an unbroken chain of change stretching back tens of millions of years. Few evolutionary lineages offer such clarity.

Much of this work began in the 19th century, when paleontologists like Othniel Charles Marsh and Richard Owen collected fossils across the American West and Europe. In the 1870s, Thomas Huxley—Darwin’s staunch defender—used horse evolution as a case study to support natural selection. The clear progression of size, tooth structure, and limb anatomy was hard to refute.

But science has moved beyond the idea of a simple ladder of progress. We now understand horse evolution as a branching tree with many dead ends. Dozens of genera and hundreds of species have come and gone. Some adapted to their niches only to vanish when the climate changed or when better-adapted competitors arose.

Still, the arc is undeniable. The fossil record captures not only the bones of horses but the history of the Earth itself—its shifting climates, its rising and falling continents, its interplay of chance and necessity.

A Bond Forged in Evolution

The modern horse is a creature of paradox. Wild yet domesticated, ancient yet modern, it is a living embodiment of deep time. Its hooves echo with the memory of its tiny forest-dwelling ancestors. Its teeth carry the marks of ancient grasses. Its gait, its breath, its gaze—these are evolutionary relics as much as they are living traits.

But perhaps what is most remarkable is how closely entwined the horse’s journey has become with our own. We did not invent the horse, but we have shaped it—and it, in turn, has shaped us. The horse helped build civilizations, wage wars, carry goods, and inspire poets. It has become a symbol of nobility, freedom, and untamed spirit.

And yet, at its core, it remains what it always was: an animal exquisitely tuned to survival, adaptation, and motion.

Looking Ahead: The Future of the Horse

Today, horses no longer plow most of our fields or carry soldiers into battle. They race on tracks, jump fences, and live in stables. Many exist for sport, companionship, or heritage. But their survival continues to depend on us.

Conservation efforts have saved rare breeds and reintroduced wild horses to protected ranges. Genetic research deepens our understanding of their evolutionary path. Ethical debates swirl around their treatment in sport and entertainment.

The 55-million-year journey of the horse is not over. Evolution continues, and so does our relationship. Whether we treat horses as machines, companions, or relics of a bygone era, their legacy remains profound.

To watch a horse run—muscles rippling, nostrils flaring, hooves pounding—is to witness the culmination of eons. It is to see time made flesh, history in motion, evolution alive.