Some questions are so profound, so fundamental to our understanding of ourselves, that they refuse to go away. They echo in the corridors of classrooms, in the silence of stargazers, in the whispered prayers of poets, and in the exacting minds of scientists. One of those questions is this: Are humans still evolving? Have we reached the end of our evolutionary journey, or are we still riding the long and winding current of natural selection?

It’s a question tangled in biology, philosophy, and wonder. For many, the very idea seems contradictory. We no longer chase prey across the savanna. We’ve tamed our environment—or at least we think we have. We fly through the air, send messages across oceans, repair failing hearts, and even edit genes. Surely we’ve risen above evolution. Haven’t we?

The answer, as it turns out, is more complex, more beautiful, and more human than most people imagine. Because the story of evolution isn’t a relic buried in rock. It’s a pulse that still beats within us, every second of every day.

What Evolution Really Means

To understand whether humans are still evolving, we need to begin with clarity. Evolution is not a goal. It is not progress toward perfection. It’s not about getting stronger, smarter, or more attractive—at least, not in any absolute sense. Evolution is simply change in the genetic makeup of a population over time. That change can come through mutations, natural selection, genetic drift, gene flow, or even sexual selection.

It doesn’t require the birth of a new species. It doesn’t require visible transformations. It only requires differential survival and reproduction—that some individuals, due to their genes, are more likely to pass on those genes to the next generation.

In that light, the question “Are humans still evolving?” becomes more than just academic. It becomes personal. Every time a child is born, every time a disease strikes or a mutation arises, every time someone falls in love, chooses a partner, or survives a famine—we are participating in evolution. Whether we realize it or not.

Evolution Didn’t Stop at the Neck

One of the most persistent myths in popular culture is that human evolution “stopped” once we began creating civilization. Some claim that fire, clothing, agriculture, and especially modern medicine have allowed people to survive who otherwise wouldn’t, thereby shielding us from the harsh culling effects of natural selection. In this view, humanity stepped off the evolutionary treadmill somewhere between the Neolithic Revolution and the Industrial Age.

But this idea collapses under scientific scrutiny.

Consider lactose tolerance. Most mammals lose the ability to digest lactose, the sugar in milk, after weaning. But some human populations—particularly those in Europe, the Middle East, and parts of Africa—evolved a mutation that allows adults to digest milk. This genetic change didn’t happen thousands of years ago; it emerged in the last 5,000 to 10,000 years—a blink in evolutionary time.

Or take the sickle-cell trait. In regions where malaria is common, people with one copy of the sickle-cell gene are more likely to survive. Despite the risks associated with having two copies (which causes sickle-cell disease), the trait persists. That’s evolution in action—natural selection shaped by environmental pressures.

More recently, we’ve discovered that the human brain itself may be evolving. A study in 2019 found that a variant of a gene called microcephalin, which influences brain development, has rapidly increased in frequency in certain populations over the last 37,000 years. While the full implications aren’t yet understood, it’s clear: our biology is still moving.

The Genetic Revolution: Evolution in Real Time

The 21st century brought us something Darwin never dreamed of—genomics. By sequencing DNA from people all over the world, scientists can now track how genes have changed over time. And the data is astonishing.

For example, we now know that humans and Neanderthals interbred, leaving traces of Neanderthal DNA in modern humans, particularly those of European and Asian descent. These genes affect everything from immune responses to skin tone. That interbreeding, which happened about 50,000 to 60,000 years ago, was not just a footnote in our history. It was a crucial infusion of genetic diversity.

Then there’s the phenomenon of polygenic traits—complex characteristics influenced by many genes, like height, intelligence, or skin color. Studies using large biobanks of genetic data (such as the UK Biobank) have shown that some alleles associated with education level, reproduction rate, and even metabolic health are under selection pressure right now. It’s subtle. It’s slow. But it’s real.

What’s more, mutations continue to arise. Every human baby is born with about 60 new mutations—tiny edits in the DNA code. Most are harmless. Some are harmful. A few may confer advantages. And in the long run, they can shift populations.

Evolution hasn’t stopped. We’re just finally able to watch it happen.

The Forces Still Shaping Us

To see how humans are still evolving, we need to look at the evolutionary forces still at work today.

First, there’s natural selection. Even in the age of modern medicine, not all individuals are equally likely to reproduce. Some genes still increase survival or reproductive success more than others. Women with certain hormone profiles may have more children. People with certain immune genes may resist new pathogens better.

Then there’s sexual selection—traits that increase an individual’s chances of mating, even if they don’t help with survival. Human culture complicates this force immensely. Attractiveness, humor, intelligence, status—all are variables influenced by genes, environment, and social norms. But selection still operates here, influencing who finds mates and who does not.

There’s also genetic drift, the random change in allele frequencies. In small or isolated populations, this can have dramatic effects. Founder effects, bottlenecks, and migration patterns all alter the gene pool.

And of course, cultural evolution—a unique trait of our species—interacts with genetic evolution in profound ways. The spread of agriculture changed our skeletons, our diets, our microbiomes. The rise of technology influences how we learn, communicate, and even select partners. Each innovation creates new selective environments.

Even epigenetics—changes in gene expression without altering DNA—suggests that our biology can adapt to new circumstances faster than we thought. Stress, diet, and environment can “switch on” or “switch off” certain genes. Some of these changes may even be inherited.

Disease, Immunity, and the Arms Race Inside Us

One of the most dynamic arenas of modern human evolution is disease resistance. We are locked in an ongoing evolutionary arms race with pathogens, which mutate far faster than we do.

Consider HIV resistance. A small number of people carry a mutation called CCR5-Δ32, which makes them highly resistant to HIV. This mutation is especially common in Northern Europe and may have been selected for during past epidemics like the bubonic plague or smallpox.

Or look at the global COVID-19 pandemic. Preliminary genetic studies revealed that people with certain variants on chromosome 3—likely inherited from Neanderthals—were more likely to develop severe illness. In contrast, other variants conferred protection.

Each outbreak tests our species. Each generation that survives passes along its secrets. Evolution is not paused. It’s playing out in hospitals and households around the globe.

Reproduction in the Modern World

Reproduction is the currency of evolution. And in the modern world, the dynamics of reproduction are shifting dramatically.

Fertility rates are declining in many parts of the world. In some countries, like South Korea and Italy, birth rates have dropped below replacement level. Others are seeing a demographic transition: as education, wealth, and healthcare improve, families choose to have fewer children. This creates new evolutionary pressures.

Surprisingly, some traits correlated with higher fertility are still being selected for, even in rich countries. Studies in Iceland and the United States have found that women who have more children tend to carry certain genetic markers—some related to early puberty, others to lower educational attainment. This doesn’t mean intelligence is declining (as often misreported), but it does highlight the subtle ways selection can operate, even in affluent, technologically advanced societies.

Another shift is the rise of assisted reproductive technologies—IVF, egg freezing, surrogacy. These tools allow people with fertility issues or delayed parenthood to reproduce, changing the evolutionary playing field. What was once a genetic dead-end is now a viable lineage.

The Environment Is Still Changing—and So Are We

Climate change is altering the world at a terrifying pace. Rising temperatures, shifting rainfall patterns, and disappearing ecosystems are not just environmental issues—they are evolutionary engines.

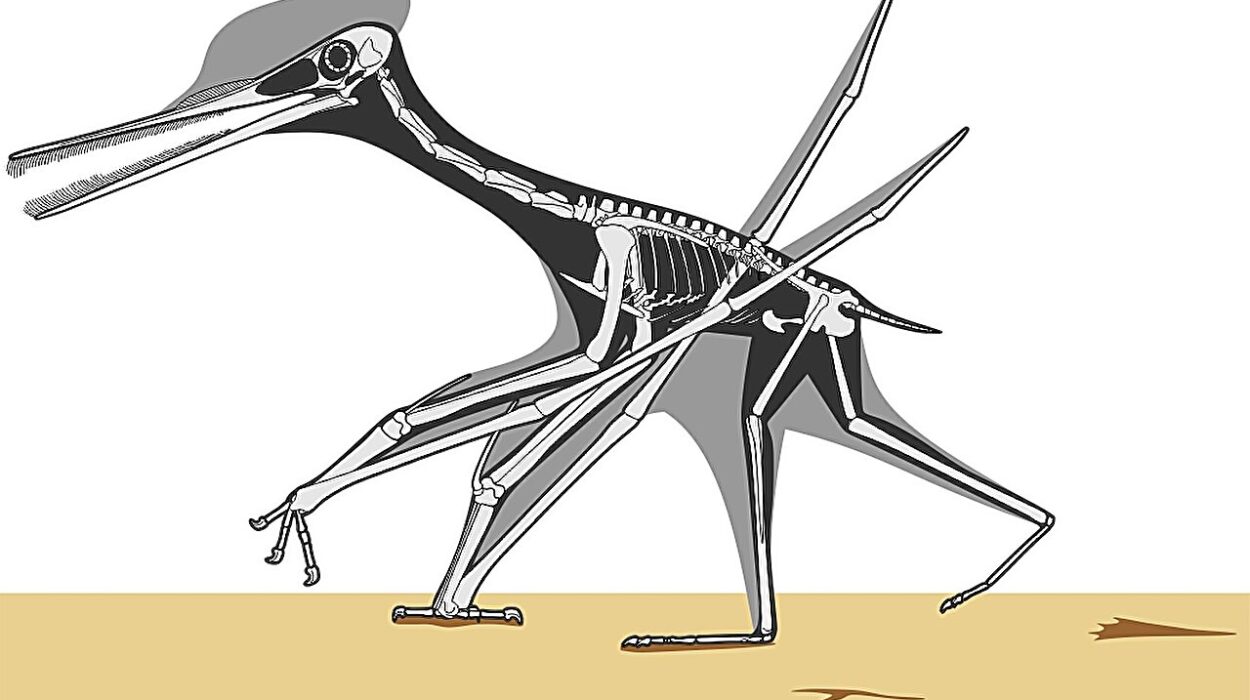

In high altitudes like the Tibetan Plateau or the Andes, human populations have evolved unique adaptations for breathing in thin air. Tibetans, for example, have a variant of the EPAS1 gene, which helps them avoid chronic mountain sickness. This gene likely came from an extinct species of ancient humans known as the Denisovans.

As climate shifts accelerate, new selective pressures will emerge. People who can tolerate heat better, resist new diseases, or metabolize different foods may have a biological edge. Urbanization also creates new environments—full of pollution, noise, and stress—which may affect human physiology and behavior in unexpected ways.

The Digital Age: Evolution Meets Technology

The digital world is not separate from the biological world. Our brains evolved in the context of physical reality, but now we navigate a virtual one filled with screens, algorithms, and 24/7 connectivity.

Some scientists argue that we’re undergoing cognitive offloading—outsourcing memory and navigation to phones, delegating knowledge to search engines. Whether this will change our brains structurally is still debated, but it’s clear that cultural evolution is moving faster than genetic evolution ever could.

We also live in the age of gene editing. Tools like CRISPR allow us to change the very code of life. What once took millennia of natural selection can now be done in a lab in days. This introduces a new concept: directed evolution—not guided by nature, but by intention. It opens doors to curing genetic diseases, enhancing traits, or even redesigning humanity.

The ethical implications are staggering. Who decides what should be edited? What traits are “desirable”? Could this create a genetic underclass? These are not distant questions. They are part of our evolution now.

Evolution Never Promised Perfection

In the end, it’s important to remember that evolution is not perfect. It’s not designed. It’s not even always beneficial. It’s messy, full of compromises and contingencies.

Our bodies still carry flaws—a narrow birth canal, weak backs, vulnerable knees, crowded teeth. Our minds still harbor outdated instincts for tribalism, aggression, and short-term gratification. We evolved for survival in small groups, not for thriving in a world of 8 billion people and global problems.

But those imperfections are part of the human story. They remind us that we are not finished. We are not static. We are still becoming.

So, Are Humans Still Evolving?

Yes. Undeniably, beautifully, constantly.

We evolve in our genes and in our cultures. In the mutations passed quietly between generations. In the whispered instructions of the genome. In the choices we make, the tools we build, the partners we choose, the babies we raise. We evolve in resistance to viruses, in the shadows of climate change, in the glow of artificial intelligence.

Human evolution is not over. It has simply changed form. It is no longer a linear march through savannas, but a kaleidoscope of possibilities—some shaped by nature, others by choice. It is evolution with a mirror in its hand, staring at itself.

The real question isn’t whether we are still evolving.

The real question is: What kind of humans do we want to become?