What makes us human? This question has echoed across the ages—from ancient philosophers who pondered the soul, to modern neuroscientists mapping circuits in the brain. Yet perhaps the more intriguing question is how we came to be this way. How did Homo sapiens—a once-naked ape wandering African savannas—become capable of painting cave walls, decoding the stars, composing symphonies, building civilizations, and dreaming of artificial intelligence?

At the heart of this story lies human intelligence. It is the most complex product of biological evolution, an ever-shifting tapestry of memory, language, reasoning, emotion, and imagination. And it did not arrive in an instant. It emerged gradually, shaped by natural selection, ecological challenges, social interactions, and cultural innovations. The path was not linear, but winding and mysterious.

Understanding the evolution of human intelligence means stepping back in time—millions of years—to trace the deep roots of our cognitive abilities. It means peering into fossilized skulls, decoding ancient genomes, and contemplating what it truly means to think. But it also means honoring the fact that intelligence is not just a trait; it is a process, a mirror of the human condition, and perhaps our species’ greatest survival tool.

Brains Before Us: Intelligence in Our Distant Ancestors

Before there were humans, there were ancestors. And before those ancestors, there were animals whose brains first began to sense, remember, and act. Intelligence, in its broadest sense, did not begin with Homo sapiens, or even with mammals. It evolved in simple forms long before our lineage took shape.

Even insects demonstrate forms of intelligence—navigating mazes, recognizing patterns, and communicating with pheromones. Cephalopods like octopuses exhibit startling problem-solving skills. Birds, especially corvids and parrots, craft tools and solve puzzles. Dolphins recognize themselves in mirrors and mourn their dead. These animals are not “human smart,” but they reveal that intelligence is not all-or-nothing. It exists on a continuum, with different species evolving cognitive adaptations suited to their environments.

In our own evolutionary tree, primates took a significant leap. Around 60 million years ago, early primates developed forward-facing eyes, better depth perception, and more dexterous hands. These traits, combined with social living and arboreal life, began selecting for greater cognitive flexibility. By 30 million years ago, the ancestors of monkeys and apes had expanded neocortices—layers of the brain crucial for higher-order thinking.

The great apes—gorillas, orangutans, chimpanzees, and bonobos—share more than 98% of their DNA with humans. They laugh, grieve, use tools, and show rudimentary forms of empathy and culture. But even their most impressive mental feats pale beside the human mind. Somewhere between them and us, something extraordinary occurred. Not just more intelligence—but a different kind of intelligence.

The Rise of the Genus Homo: Big Brains, Bold Ideas

The story of human intelligence begins in earnest with the genus Homo. Around 2.5 million years ago, early hominins like Homo habilis began to appear in Africa. These were upright-walking creatures with slightly larger brains than their australopithecine ancestors. They are often credited with the first deliberate tool-making—fashioning sharp stones for cutting meat or breaking bones. This marks a key transition: from reactive behavior to planning and foresight.

As millions of years passed, the brain continued to grow. Homo erectus, emerging around 1.8 million years ago, had a brain nearly twice the size of earlier hominins. They controlled fire, traveled long distances, and likely communicated in complex vocal patterns. Their stone tools became more sophisticated, reflecting growing cognitive control and spatial awareness.

But bigger brains are costly. The human brain consumes about 20% of our energy at rest, despite accounting for just 2% of our body mass. Evolution does not grant such a luxury unless the payoff is massive. For our ancestors, that payoff came from a changing environment. As forests gave way to open grasslands, hominins faced new threats and opportunities. Success depended not on brute strength, but on adaptability—remembering where food was, collaborating in groups, and innovating when circumstances changed.

Here, intelligence became a survival trait. Those who could think, plan, and communicate had a better chance of passing on their genes. Natural selection sculpted the brain accordingly.

Social Minds and the Origins of Culture

One of the most powerful engines driving the evolution of intelligence may not have been the physical world, but the social one. Humans are profoundly social animals. We cooperate, deceive, gossip, empathize, and form intricate relationships. This complexity may have placed a premium on understanding others’ thoughts, intentions, and emotions—a capacity known as “theory of mind.”

The “Social Brain Hypothesis” suggests that the demands of living in increasingly complex social groups selected for larger brains and better cognitive skills. Keeping track of alliances, rivalries, and obligations required memory, emotional regulation, and predictive modeling of others’ behavior. In essence, we had to outsmart not just the environment, but each other.

This social intelligence laid the groundwork for culture—knowledge, behaviors, and beliefs passed from one generation to the next not by genes, but by learning. Long before written language, early humans were likely transmitting survival skills, hunting strategies, and spiritual ideas through gestures, imitation, and speech. This capacity for cultural transmission transformed the nature of evolution itself. No longer were we merely adapting to the environment—we were reshaping it, and ourselves, through shared ideas.

Language: The Explosion of Thought into Sound

Of all the tools human intelligence has forged, none is more powerful than language. It allowed our ancestors not only to share knowledge but to shape abstract concepts, plan across time, and build collective meaning.

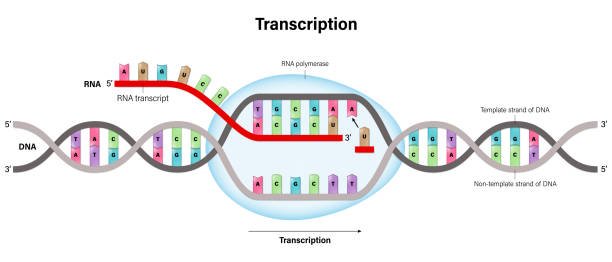

The origins of language are deeply mysterious. It leaves no fossil record, and its evolution likely occurred gradually. But studies of primates, child development, and brain function provide clues. The anatomical changes required for speech—such as a descended larynx and refined tongue control—co-evolved with neural circuits for symbolic thought and auditory memory.

By the time of Homo heidelbergensis, around 600,000 years ago, there is evidence suggesting increasingly complex vocal communication. By the time of Neanderthals and early Homo sapiens, language likely became rich and nuanced, capable of storytelling, persuasion, and abstract thought.

Language accelerated the growth of intelligence in a feedback loop. As communication improved, cooperation became more efficient. Societies grew, tasks specialized, knowledge accumulated. Ideas no longer died with their inventors—they lived on, traveling across generations and continents.

The Creative Mind: Art, Ritual, and Imagination

Roughly 100,000 years ago, a profound shift occurred. Human behavior began to exhibit symbolic thought. People carved figurines, painted on cave walls, wore jewelry, and buried their dead with care. These acts were not necessary for survival—but they spoke to something deeper: a mind capable of imagination, beauty, and belief.

This “cognitive revolution” is one of the great mysteries of anthropology. What changed in the brain to unlock this sudden creativity? Some point to genetic mutations affecting brain structure. Others argue it was a gradual cultural accumulation. Either way, by 40,000 years ago, early humans were crafting mythologies, composing music, and contemplating the afterlife.

Art and ritual are not frivolous; they are profound expressions of intelligence. They show that the human mind is not just a calculator—it is a storyteller. Through symbols and metaphors, we encode emotions, history, and values. Intelligence, in this sense, becomes deeply human—imbued with purpose and meaning.

The Neanderthal Puzzle: Were We the Only Smart Humans?

For much of the 20th century, Neanderthals were painted as brutish and dim—a failed evolutionary branch eclipsed by our brilliance. But new discoveries have radically revised that view.

Neanderthals made tools, buried their dead, likely used language, and may have created art. Their brains were as large as, or larger than, ours. They survived harsh climates for hundreds of thousands of years. Genetic evidence now shows they interbred with modern humans; most people today carry some Neanderthal DNA.

So why did they disappear? It’s possible that Homo sapiens had an edge in social cohesion, technological innovation, or symbolic communication. Or perhaps it wasn’t a matter of superiority, but bad luck and changing environments. Either way, Neanderthals challenge the idea that intelligence was uniquely ours. The truth may be more humbling: we were not alone in our spark of genius—we just happened to be the last flame that survived.

The Agricultural Revolution and the Architecture of Thought

Around 12,000 years ago, the invention of agriculture transformed human life. Settled communities replaced nomadic tribes. Cities arose. Writing systems emerged. Societies became more hierarchical, specialized, and organized.

This shift did not necessarily increase raw intelligence, but it did restructure how it was used. Problem-solving turned toward management, logistics, and governance. The written word expanded memory beyond the individual mind. Formal education began to shape how knowledge was stored and shared.

With civilization came complexity. And with complexity, new demands on the brain. Mathematics, law, philosophy, engineering—these were extensions of the same problem-solving instincts that helped our ancestors track prey or find edible roots. The context had changed, but the underlying cognitive engine remained the same.

Intelligence in the Modern Age: Biology Meets Technology

In the blink of an evolutionary eye, humanity entered the modern era. From steam engines to space stations, the rate of technological and cultural change exploded. Today, artificial intelligence threatens to surpass human cognition in narrow domains. We now ask whether we are evolving biologically—or outsourcing evolution to our machines.

Neuroscience reveals that the human brain is still adapting. Certain regions are becoming more active in response to digital environments. Plasticity—the brain’s ability to rewire itself—remains a hallmark of our intelligence. But it raises questions: Are we smarter than our ancestors, or simply differently skilled? Is modern life enhancing our minds—or overwhelming them?

There is no single answer. Intelligence is multifaceted: emotional, logical, creative, social. What has changed is not our genetic code, but the landscape in which our intelligence operates. In this new world, the ability to learn, adapt, and understand others may matter more than ever.

The Future of Intelligence: Evolution Continues

Human intelligence did not stop evolving when we invented the wheel—or the smartphone. Evolution is ongoing. Some researchers suggest we may be experiencing “cultural evolution” at a faster pace than genetic change. Ideas evolve, compete, mutate, and spread like viruses, shaping our minds in the process.

Others speculate that we may eventually engineer our own evolution. Genetic editing, brain-machine interfaces, and artificial enhancement could change not just how we think—but what we are.

But such possibilities come with profound ethical questions. What is intelligence for? Who gets to shape it? How do we preserve humanity in a world of accelerating change?

If evolution has taught us anything, it is that intelligence is not an endpoint. It is a journey. A river that flows through time, shaped by pressure, chance, and necessity. We are not its masters—but its current carriers.

The Human Mind: A Miracle of Time

From the whispers of primate ancestors to the roar of rocket engines, human intelligence has been the unseen hand behind our story. It is not just the ability to solve problems, but to dream, to connect, to care, to imagine a world not as it is, but as it could be.

We are the product of millions of years of brains learning to understand the universe—and themselves. Each thought you think, each word you speak, is built on that ancient scaffolding. The mind is not a machine. It is a flame—a living, dancing miracle.

And like all things shaped by evolution, it is not perfect. It is emotional, biased, forgetful. But it is also curious, compassionate, and capable of transcending its origins.

As we stand on the edge of new frontiers—from neural implants to artificial minds—we would do well to remember this: intelligence is not a trophy, but a trust. It is the gift that brought us fire, poetry, justice, and love. And it is up to us to ensure that it continues to evolve—not just upward, but inward and outward, toward understanding, humility, and wisdom.