Walk through a dense rainforest in Africa or Southeast Asia, and if you’re lucky, you might catch a glimpse of another pair of eyes looking back. They are ancient eyes, deep-set and familiar. A chimpanzee sits in a tree, watching you—not as prey, not as predator, but as something else. There’s recognition there. You are not strangers. You are kin.

For millions of years, humans and other primates have shared the same evolutionary stage, shaped by the same laws of nature. We are not as far apart as we often believe. Our DNA tells the story of a common ancestry. Chimpanzees, our closest living relatives, share nearly 99% of our genetic code. Bonobos, gorillas, and orangutans are not far behind. We all descended from a common primate ancestor who lived 5 to 8 million years ago.

But while other primates still swing from trees or roam tropical forests, humans have landed on the Moon, painted the Sistine Chapel, split the atom, and searched the heavens for meaning. Something, somewhere along the journey, set us on a radically different path.

So, what is it? What makes us so different?

Bones, Brains, and Bipedalism

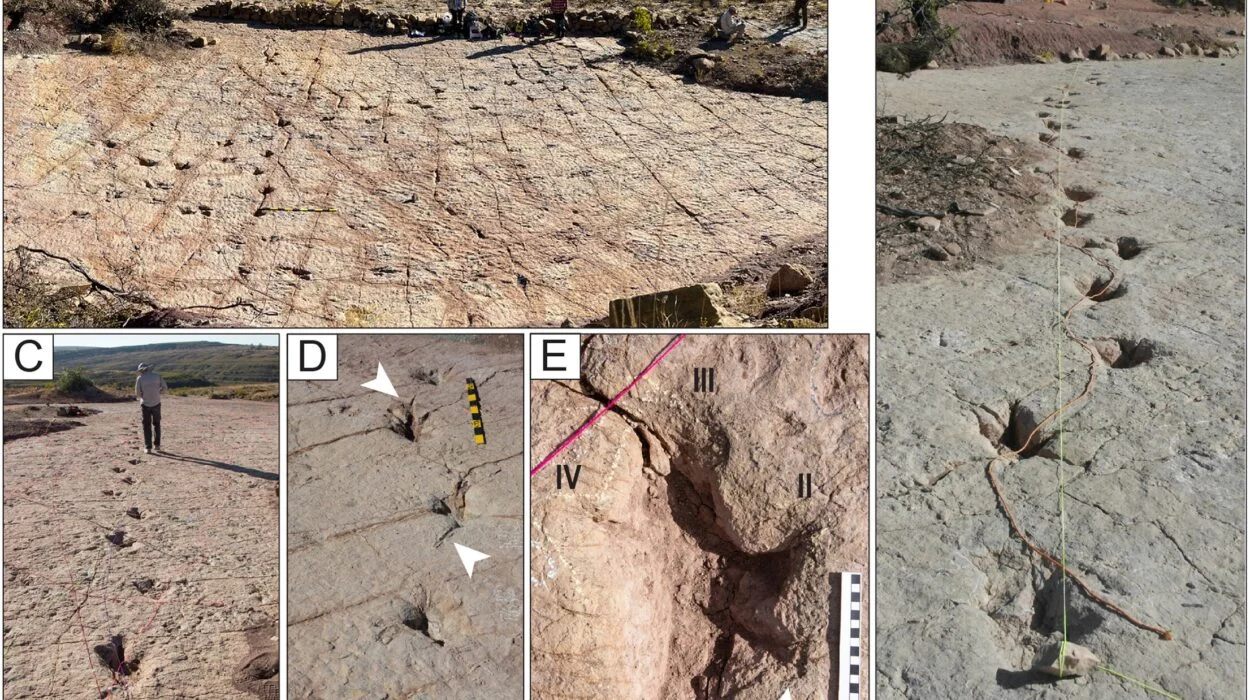

At first glance, the differences between humans and other primates seem obvious. Look at our posture: we walk upright on two legs while most primates move on all fours or swing through trees. This ability to walk upright—bipedalism—is one of the earliest and most crucial steps in human evolution. Fossil evidence suggests our ancestors began walking upright over 6 million years ago, long before our brains grew large or tools were crafted.

The shift to bipedalism didn’t just change how we moved—it transformed everything. With our hands freed from the task of locomotion, they became tools of manipulation, creation, and expression. Our ancestors could carry food, fashion weapons, or gesture to others, opening doors to language and cooperation. Standing tall also allowed for better surveillance of the savanna, helping early hominins avoid predators and find food.

But bipedalism came at a cost. Human childbirth is uniquely difficult among primates, largely because of the tradeoff between our big-brained babies and narrow pelvises needed for efficient upright walking. This tension meant babies had to be born earlier in development, requiring extended periods of care and nurturing—a factor that laid the foundation for our complex social systems.

Then came the brain. Compared to our primate relatives, humans have extraordinarily large and metabolically expensive brains. The human brain is three times larger than that of a chimpanzee. And more than size, it is the structure of our brains that sets us apart—particularly the neocortex, which governs higher-order functions like reasoning, planning, imagination, and social behavior.

This enhanced brain power didn’t evolve in a vacuum. It was shaped by our interactions, our need to cooperate, compete, and understand one another. The pressures of social living, of navigating alliances, detecting deception, and raising vulnerable offspring, drove the evolution of our cognitive complexity. We became creatures of community, shaped not only by survival but by our capacity to live together.

The Word Made Flesh: Language and Symbolic Thought

While many animals communicate—bees dance, dolphins whistle, wolves howl—only humans possess true language: an open-ended system capable of infinite expression. Our language is not just a set of calls or signals, but a generative, symbolic system that allows us to convey ideas, ask questions, tell stories, and imagine futures.

No other primate comes close. Chimpanzees can learn rudimentary sign language or symbols, but their use is limited, inflexible, and heavily reliant on human trainers. Only humans use language to build worlds, express abstract ideas, or ponder existence itself.

Language transformed our species. It allowed knowledge to be passed across generations, cultures to flourish, and civilizations to rise. It enabled empathy, law, science, religion, and art. With words, we can mourn the dead, comfort the grieving, teach the young, and inspire change.

Beneath our words lies another uniquely human capacity: symbolic thought. We see it in our earliest ancestors—Homo sapiens who painted animals on cave walls, carved figurines from ivory, and buried their dead with rituals. Symbolic thought allows us to represent things that are not present, to understand metaphor and myth, to create gods, nations, and ideals. It is the root of all culture, all religion, all imagination.

No chimpanzee has ever carved a statue, written a poem, or dreamed of eternity.

The Hand That Shapes the World

A chimpanzee’s hand is remarkably like our own. It has opposable thumbs, strong fingers, and excellent dexterity. Yet the human hand is more finely tuned. Our fingers are longer and more agile. Our thumbs are uniquely muscular, allowing for a precision grip that no other primate can match.

This seemingly small difference has enormous consequences. It gave us the power to make tools, not just simple sticks or stones, but spears, axes, sewing needles, and eventually, microchips and spacecraft.

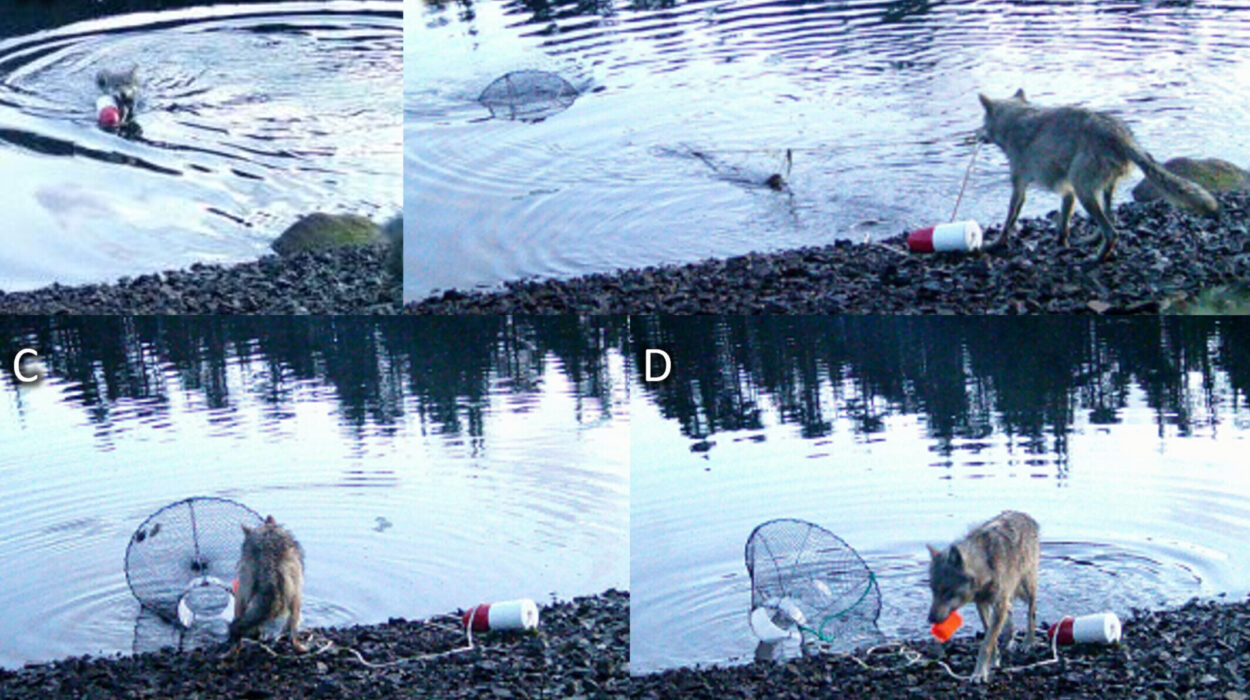

Tool use itself is not exclusive to humans. Chimpanzees use sticks to fish termites from mounds, capuchins crack nuts with rocks, and orangutans fashion makeshift umbrellas from leaves. But only humans have developed cumulative culture—where tools are not just used, but refined, passed down, and improved over generations.

This cumulative culture is central to our uniqueness. A child today can benefit from the knowledge of millennia—walking into a classroom and learning about DNA, the solar system, or algebra, standing on the shoulders of countless others. Knowledge compounds in human societies in a way it simply does not in the animal kingdom.

Our tools became extensions of ourselves, amplifying our power and reshaping our environment. From fire to farming, from wheel to web, humans have not just adapted to nature—we have altered it.

The Fires of Emotion and Empathy

It’s tempting to think that our differences are all in the brain, in abstract thought and clever tools. But some of the most profound human traits are emotional. We laugh, we cry, we fall in love, we grieve, we hope. These feelings are not exclusive to humans—many animals feel pain, show affection, or suffer loss—but humans experience them with a depth, range, and social context that appears unparalleled.

Empathy, in particular, is central to our nature. We do not merely react to others’ emotions; we imagine what it feels like to be them. This capacity for theory of mind—understanding that others have thoughts and feelings different from our own—is what allows us to tell stories, deceive, console, forgive, and collaborate.

Our emotional lives are the glue of society. Without empathy, there would be no shared values, no moral systems, no collective action. It is empathy that allows us to care for the sick, protect the weak, and sacrifice for others. It is why we mourn strangers lost in distant disasters or cry during films we know are fiction.

This emotional richness is not a side effect of intelligence—it is a core part of being human.

Culture, Cooperation, and the Web of Society

Other primates live in groups. They groom each other, form alliances, and raise young together. But no other species has built a society as vast, complex, and interconnected as ours.

Human cooperation is astonishing. We build cities of millions, engage in global trade, and follow systems of law, government, and religion. We form communities not just with those we know personally, but with strangers. We rally behind flags, creeds, ideologies, and sports teams. We create and enforce social norms, tell myths to explain our origins, and pass on traditions through ritual and art.

This web of culture is unique. It is not written in our genes but carried in stories, songs, books, and memories. And it is always evolving. Each generation reshapes it, adding new voices and visions.

No other primate can write a constitution, perform a play, or crowdsource funding for a scientific project.

Culture also allows us to be flexible. While other animals are largely bound to their ecological niches, humans can thrive in tundras, deserts, rainforests, and skyscrapers. We adapt not by growing fur or fangs, but by changing ideas, clothes, tools, and stories.

Morality, Meaning, and the Search for the Sacred

Perhaps the most mysterious difference lies not in what we do, but in what we seek. Humans are not content with survival—we search for meaning. We ponder our origins and destiny. We wonder why we exist. We imagine gods, ask moral questions, and seek transcendence.

No other primate builds temples, writes sacred texts, or fears damnation. No chimpanzee ever asked, “What is justice?” or “What happens after death?”

This search for meaning is both beautiful and terrifying. It gives us poetry and philosophy, but also fanaticism and fear. It drives our highest ideals and our darkest moments.

From the beginning, humans have buried their dead, honored ancestors, and looked to the stars with longing. This spiritual impulse may be rooted in our awareness of mortality, our ability to imagine futures that do not yet exist—and never might.

The human mind is not just an engine of logic, but a theater of dreams. We do not simply want to live—we want to matter.

The Shadow Side: War, Cruelty, and the Power to Destroy

For all our brilliance and beauty, humanity also casts a long shadow. We are the only species capable of genocide, of building weapons that can erase cities or ecosystems. Our drive for dominance, our tribal instincts, and our thirst for power have fueled countless wars, oppressions, and injustices.

Other primates fight, yes. Chimpanzees even wage territorial skirmishes. But only humans kill in the name of ideas. Only humans enslave others, burn books, or poison rivers for profit.

This dark capacity is not separate from our intelligence—it is part of it. Our creativity can be twisted. Our empathy can be limited to “our kind.” Our stories can be used to unite or divide, to heal or to hate.

To be human is to carry both light and shadow—to be capable of astonishing love and appalling cruelty.

A Species Still Evolving

Despite our technological achievements and cultural complexity, humans are still animals. We are still evolving. Our bodies, minds, and societies continue to change in response to the pressures of our environment, including the ones we create ourselves.

Genetic studies show subtle changes in human populations over time—adaptations to high altitudes, resistance to disease, and even changes in brain structure. Our social evolution is even faster. In a matter of centuries, we’ve gone from horse-drawn carts to quantum computers, from tribal villages to global networks.

The journey is not over. If anything, it is accelerating.

What we will become depends not only on biology, but on choice. Evolution has given us a powerful mind—but not a guarantee of wisdom.

A Kinship Worth Remembering

In our search for what makes us different, it’s easy to forget what makes us the same. We are still primates. We still share a deep kinship with the chimpanzee in the tree, the gorilla in the mist, the orangutan in the canopy. We share laughter, pain, play, and motherhood. We share the basic architecture of our brains, the chemistry of our blood, the beating of our hearts.

To understand our differences is not to deny our connection—it is to deepen it.

Humans are unique, yes. But not because we stand above nature. We are unique because of how we stand within it—reflecting, reshaping, and reaching beyond what came before.

We are stardust that dreams. Apes that wonder. Flesh that speaks.

And somewhere in a forest, another pair of eyes watches us, silently.