In the vast and varied realm of mammals, few stories of motherhood are as remarkable as those found among marsupials. These animals, including kangaroos, koalas, wombats, possums, and bandicoots, are famous for one evolutionary trait that sets them apart from their placental relatives: they raise their young in a pouch. But this pouch is no simple fold of skin. It is a biological cradle, a mobile nursery that provides warmth, nourishment, protection, and even immunological support to the most fragile of newborns.

While the idea of a baby nestled safely in its mother’s pouch is endearing, the science behind marsupial reproduction is nothing short of astonishing. It is a tale of embryonic feats, physiological ingenuity, and maternal devotion shaped by millions of years of evolutionary adaptation. The pouch is not merely a place to carry young—it is a microenvironment tuned to the survival needs of some of the smallest, most vulnerable creatures in the animal kingdom.

Understanding how marsupials nurture their young requires more than admiration for their cuteness. It calls for an exploration into developmental biology, reproductive strategies, and ecological adaptation. This is the story of how life begins, continues, and thrives—in the pouch.

Evolution’s Divergent Paths

To grasp the uniqueness of marsupial reproduction, we must first understand where they fit in the broader mammalian lineage. Mammals are divided into three main groups: monotremes, marsupials, and eutherians (placental mammals). Monotremes, such as the platypus and echidna, lay eggs. Eutherians, which include humans, elephants, and whales, carry their young in a womb connected by a placenta, allowing extended gestation and development before birth.

Marsupials took a different evolutionary route. Rather than developing a complex placenta that allows for prolonged internal gestation, they evolved to give birth at a much earlier stage. Marsupial embryos leave the uterus at a time when they are scarcely more than a cluster of developing tissues—blind, hairless, and weighing just fractions of a gram. Their survival hinges on their ability to immediately latch onto a teat and remain securely in the mother’s pouch, where they continue the majority of their development.

This divergence likely began around 160 million years ago. As landmasses drifted and climates changed, marsupials found ecological advantages in producing many young over time, each requiring fewer maternal resources per pregnancy. It was a strategy that traded long internal development for postnatal care in an external, yet protected, environment.

Birth Before They’re Ready

One of the most astonishing facts about marsupial young is how undeveloped they are at birth. In kangaroos, for instance, the newborn, called a joey, emerges from the mother’s birth canal after just 33 days of gestation. It is barely two centimeters long—about the size of a jellybean—and weighs less than a gram. It has no functional eyes, no ears, no fur, and no ability to regulate its own body temperature. In most species, the forelimbs and mouth are more developed than the rest of the body, which is crucial for the next vital step: the climb.

Immediately after birth, the joey begins a journey that is both perilous and heroic. With forelimbs adapted for grasping, the tiny creature climbs from the birth canal, across the mother’s fur, and into the pouch. This instinctual migration is not guided by sight or sound, but rather by innate tactile responses and chemical cues. Once inside the pouch, the joey finds a teat, latches on tightly, and begins to feed. This moment marks the start of a second, much longer developmental phase—one that takes place entirely within the pouch.

The Pouch: Nature’s Incubator

The marsupial pouch, known scientifically as the marsupium, is a marvel of evolutionary engineering. Far from being a passive pocket, it is a dynamic and responsive environment designed to mimic the womb while compensating for its premature departure.

The interior of the pouch is lined with skin that produces antimicrobial secretions to keep the space sterile. This is vital, given the vulnerability of the joey’s undeveloped immune system. In many species, the temperature within the pouch is regulated by the mother’s body, maintaining an optimal climate for the joey’s growth. Some studies have shown that pouch temperature can be adjusted subtly to align with the developmental stage of the occupant.

One of the most extraordinary features of the pouch is the mother’s ability to manage multiple offspring at different stages. In kangaroos and wallabies, for example, a female can simultaneously support three young: one fertilized embryo held in suspended animation (a process called embryonic diapause), one developing joey attached to a teat inside the pouch, and one older joey that has left the pouch but still nurses periodically. Each teat can produce milk of a different composition to match the needs of each offspring.

This lactational complexity is a testament to the finely tuned coordination between mother and young. The milk changes in nutrient content, fat levels, and immunological compounds as the joey matures. Early milk is rich in carbohydrates to fuel rapid cell growth, while later milk contains more fats and proteins to support muscular development and immune resilience.

Immune Lessons from the Pouch

One of the most pressing challenges for newborn marsupials is their undeveloped immune system. Born at a stage comparable to an 8-week-old human fetus, marsupial joeys lack the innate defenses necessary to combat infections. The pouch, therefore, must function as both a barrier and a training ground.

Recent research has illuminated how the pouch’s lining produces a host of antimicrobial peptides—molecules that actively neutralize bacteria, fungi, and viruses. These peptides create a biologically “clean room” within which the joey can safely grow. Meanwhile, the mother’s milk acts as an immunological instructor, transferring not just nutrients but antibodies and other immune factors tailored to pathogens in the environment.

Interestingly, the marsupial immune system matures from the outside in. As the joey grows in the pouch, it begins to develop lymphoid tissues and thymus structures necessary for adaptive immunity. This allows it to eventually mount its own defense systems, preparing it for life outside the pouch.

This process has captivated scientists not only for its elegance but for its implications in human medicine. The antimicrobial properties of marsupial milk and pouch secretions are being studied for potential use in developing new antibiotics, especially as resistance to conventional drugs increases worldwide.

Leaving the Pouch: A Delicate Transition

The time a joey spends in the pouch varies widely by species. A kangaroo may keep its young in the pouch for up to eight months, while a brushtail possum might do so for only four to five. Regardless of the duration, the transition out of the pouch marks a major developmental milestone.

The gradual weaning process begins while the joey is still nursing. It starts poking its head out, observing the world, and eventually taking short exploratory trips while still retreating to the pouch for safety and nourishment. These excursions help it learn social cues, navigation, and feeding behaviors.

Eventually, the joey becomes too large to fit comfortably inside. This often leads to comical scenes of large juveniles half-dangling from pouches, limbs flailing. Yet this stage is critical. It allows the young to adapt to life outside the pouch without sudden exposure to predators or environmental stress.

Even after leaving the pouch permanently, young marsupials may continue to nurse for several months. During this time, the mother may already be nurturing a new joey in her pouch, showcasing the impressive multitasking abilities inherent in marsupial reproductive biology.

Ecological Logic and Evolutionary Elegance

Why did marsupials evolve to raise their young in this way? The answer lies partly in geography and partly in ecological trade-offs. Most marsupials are native to Australia and the surrounding regions, where environmental conditions have historically favored strategies that maximize reproductive flexibility.

The ability to give birth to undeveloped young allows marsupials to conserve energy. In uncertain or harsh environments, they can terminate a pregnancy early if resources become scarce—a feat much more difficult for placental mammals, which invest heavily in long gestation periods.

Furthermore, the external pouch allows for more continuous reproduction. With embryonic diapause, a mother can pause the development of an embryo until the current joey leaves the pouch. This staggered strategy ensures that reproductive opportunities are not missed, even in unpredictable conditions.

The pouch system also reduces the risks associated with internal birth in large or mobile animals. For example, kangaroos are built for jumping. Carrying a large fetus internally while bounding across the Outback would be energetically inefficient and potentially dangerous. The pouch resolves this by shifting the burden of development outside the uterus but within a protected and adaptable space.

Beyond Kangaroos: The Diversity of Marsupial Motherhood

While kangaroos often dominate the popular image of marsupials, the group is highly diverse, and their pouch systems vary accordingly. Koalas, for example, have a pouch that opens downward rather than upward. This anatomical quirk prevents debris from entering as the mother climbs trees. Wombats, which are burrowers, also have backward-facing pouches for similar reasons, ensuring that soil doesn’t fill the pouch during digging.

In bandicoots, the pouch has openings on either side and a more rudimentary structure. Some species of marsupials, like the numbat, barely have a pouch at all—just a fold of skin or fur that offers minimal coverage. Despite these differences, all marsupial mothers share the same underlying strategy: give birth early, and continue development in a specialized external environment.

This variation reflects the adaptability and resilience of the marsupial blueprint. Whether in forests, deserts, or grasslands, marsupials have found ways to refine and adapt their nurturing strategies to meet local challenges.

Touching Lives: Marsupials and the Human Imagination

The emotional resonance of marsupials is undeniable. The sight of a joey peeking out from a pouch evokes a primal sense of care, dependence, and maternal connection. But beyond their symbolic value, marsupials offer real insights into the complexity and plasticity of mammalian reproduction.

They remind us that motherhood comes in many forms, that nature has not prescribed a single way to nurture life. Instead, it has provided a canvas on which evolution paints endlessly creative solutions to the challenge of survival.

For indigenous cultures in Australia, marsupials have long been woven into mythology, storytelling, and spiritual belief. The kangaroo, or gangurru, is often a totem animal, representing strength, progress, and family. The pouch, in these narratives, is not just a container but a sacred space—a sanctuary of beginnings.

In a scientific context, marsupials challenge our assumptions about development. They push the boundaries of what is considered “premature” and reveal how environments—both internal and external—can be crafted to support life in its earliest and most delicate stages.

The Future of the Pouch

In an age of ecological uncertainty and rapid biodiversity loss, marsupials face growing threats from habitat destruction, invasive species, and climate change. Many are now endangered, their survival precariously linked to the efforts of conservationists and researchers.

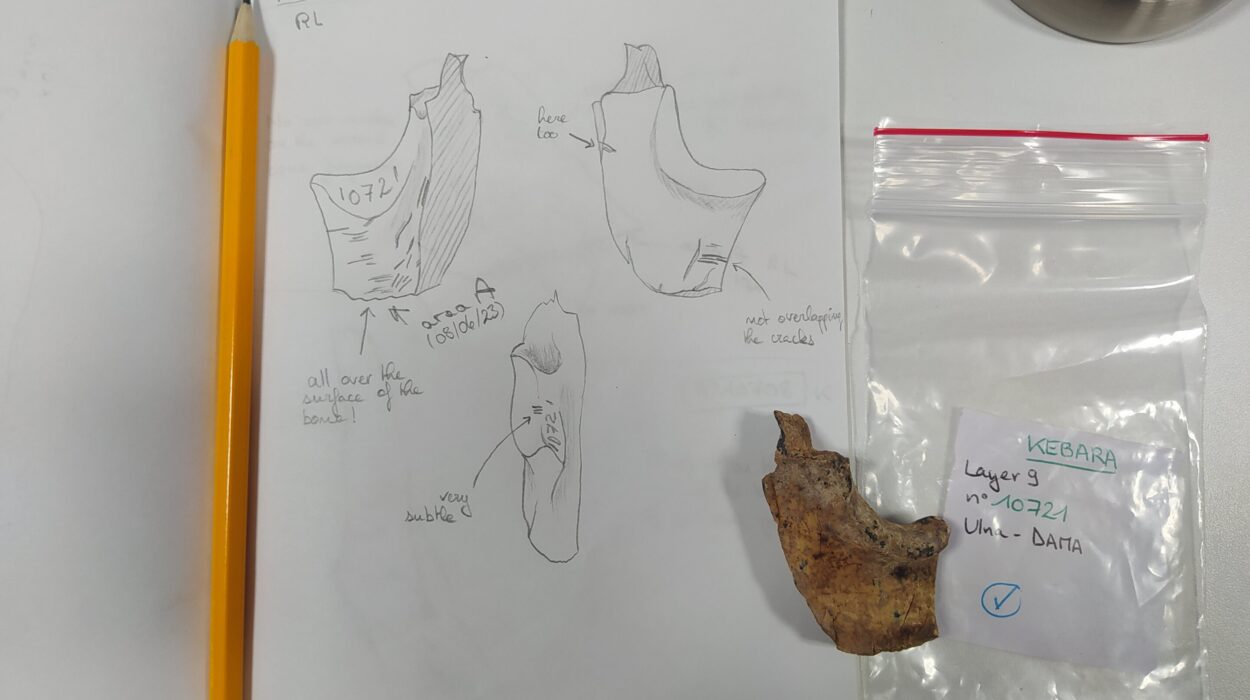

But hope remains. Advances in reproductive biology, genomics, and wildlife management are helping scientists better understand how to protect marsupial populations. Pouch biology itself is informing conservation strategies, from fostering orphaned joeys in surrogate pouches to designing artificial environments that mimic the natural marsupium.

In labs around the world, researchers study the molecular composition of pouch secretions and the hormonal controls of embryonic diapause, not only to safeguard these species but to unlock new knowledge that may one day aid human health and medicine.

The pouch—so often seen as a quaint curiosity—has become a symbol of resilience, adaptation, and the boundless ingenuity of life.

Conclusion: Cradled in Mystery and Meaning

To watch a marsupial mother care for her young is to witness a profound biological partnership. It is a story not of simplicity, but of layered complexity—a narrative of fragility held within strength, of vulnerability sheltered by evolution’s design.

In their quiet way, marsupials have redefined the essence of motherhood. They show us that nurturing can be both unconventional and perfectly suited to life’s demands. Their pouches, whether deep and warm or shallow and sparse, tell a story of continuity and care, of nature’s endless capacity to adapt and preserve.

In every joey that climbs blindly into its mother’s pouch, there is a whisper of millions of years of survival. And in every pouch that shelters, warms, and feeds, there is the enduring wonder of life—protected, nourished, and loved by design.