In the rocky wilderness of Gansu Province, tucked between arid hills and windswept sedimentary outcrops, time sits thick and unmoving. This is a place where history doesn’t just echo—it whispers in stone. Here, in a remote slice of northwestern China known more for its geological obscurity than tourist traffic, a team of paleontologists has uncovered a relic from the distant past: a near-complete skull and partial skeleton of a previously unknown dinosaur species. They named it Jinchuanloong niedu—the “Jinchuan dragon.”

The name is poetic, but the science is precise. This isn’t just another sauropod—a long-necked dinosaur that would have towered over its contemporaries in the Jurassic landscape. Jinchuanloong represents a rare and critical addition to the fossil record: a non-neosauropod eusauropod preserved from the Middle Jurassic, a pivotal and poorly understood era in dinosaur evolution. And most remarkably, it has a nearly complete skull—an astonishing find given how elusive skulls are in this branch of the dinosaur family tree.

A Skull in the Dust: Discovery in the Xinhe Formation

The discovery emerged from the lower Xinhe Formation, a Middle Jurassic geological sequence dated to the late Bathonian stage, approximately 165 to 168 million years ago. In the Jinchuan District of Gansu, field teams from the China University of Geosciences and collaborating institutions had been excavating fossil-rich layers for years, but it was only recently that their efforts yielded something truly rare: a series of articulated bones—vertebrae and skull—exquisitely preserved in the red and gray sediments.

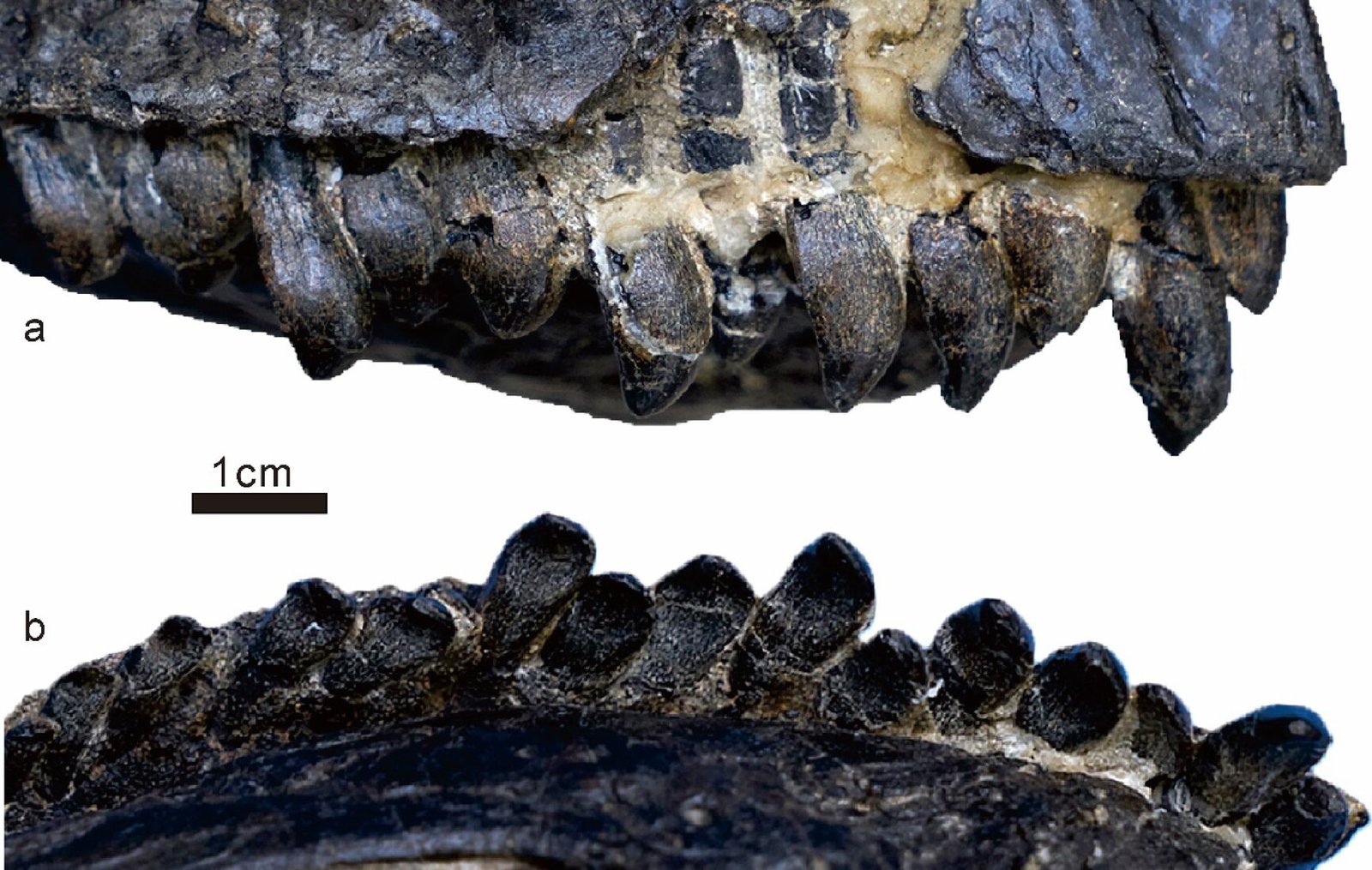

The holotype includes 29 articulated caudal (tail) vertebrae, five articulated cervical (neck) vertebrae, and a nearly complete cranium and mandible. The quality and completeness of the skull are especially noteworthy. For this branch of the sauropod lineage, which often preserves little more than necks and tails, skulls are tantalizingly scarce. Each one adds a crucial piece to a puzzle that paleontologists have long struggled to assemble.

Before the Giants: A Brief Primer on Eusauropods

To understand the significance of Jinchuanloong niedu, we have to rewind not just to the Jurassic Period, but to the evolutionary rootstock from which all sauropods emerged.

Eusauropoda—literally “true lizard feet”—is a clade that includes almost all the recognizable long-necked dinosaurs, including the iconic Apatosaurus, Diplodocus, and Brachiosaurus. But not all eusauropods were equally derived. Within this group lies a divide: early-branching, more primitive forms (non-neosauropod eusauropods), and their later descendants, the neosauropods—animals that would become the colossal, pillar-legged giants of the Late Jurassic and Cretaceous.

The early Middle Jurassic, however, remains a foggy chapter in this story. A global extinction at the end of the Early Jurassic had dramatically thinned the ranks of basal sauropodomorphs. What emerged in its wake was a new dominance by eusauropods—but the specifics of that transition are fragmentary, especially in East Asia. Most Middle Jurassic sauropod fossils are disarticulated or missing key parts like the skull.

That’s why Jinchuanloong is such a game-changer.

Anatomy of a Mystery

Describing a new dinosaur is a meticulous process—part anatomical dissection, part evolutionary detective work. The researchers, led by Xing Xu and his colleagues, conducted a detailed morphological analysis of the fossil material. They compared each element—skull bones, teeth, vertebrae—to those of other known eusauropods from China and beyond. Then, they coded the specimen’s features into two different phylogenetic datasets to determine where Jinchuanloong fits on the dinosaur family tree.

The results place it at a fascinating crossroads: a diverged non-neosauropod eusauropod, close to the base of the branch that eventually leads to Turiasaurus and Neosauropoda. This evolutionary positioning gives us a unique window into the features of early sauropods just before they exploded into diversity and size.

Several diagnostic traits support this placement. These include a distinct foramen at the base of the ascending process of the maxilla (the upper jaw bone), an aperture on the anterodorsal surface of the prefrontal (just above the eye), and a robust postorbital bone with a peculiar height-to-length ratio. Such details might seem arcane, but they matter deeply in paleontology, where subtle shifts in skull morphology can signal major evolutionary divergences.

Even the maxillary teeth offer clues. Spoon-shaped in labial view, they resemble those of Shunosaurus and Turiasaurus, hinting at both dietary preferences and evolutionary relationships. These were likely generalist feeders, capable of stripping foliage from a range of Jurassic flora.

A Juvenile Giant?

Interestingly, the specimen also shows several signs of immaturity. The neural arches in the posterior tail vertebrae are unfused—a hallmark of a juvenile or subadult dinosaur. Likewise, the presence of a large pineal foramen (a hole between the parietal bones atop the skull) is more commonly seen in younger individuals.

Despite this, the estimated body length of Jinchuanloong niedu stretches to around 10 meters (33 feet). That means even as a “teenager,” this animal was already enormous by human standards—and likely had plenty of room to grow.

The youthful status of the specimen complicates some anatomical interpretations. Features can change during ontogeny (growth), which means some traits identified in the skull may reflect age rather than strict evolutionary difference. Still, the authors emphasize that the core diagnostic features are robust enough to justify the new species.

Dragons of the Middle Jurassic

So what kind of world did Jinchuanloong inhabit?

During the Middle Jurassic, East Asia was a patchwork of river systems, floodplains, and dense forests populated by an array of ancient life. The Xinhe Formation preserves a rich assortment of vertebrate fossils, from fish and amphibians to pterosaurs and early mammals. Sauropods like Jinchuanloong would have lumbered through this landscape in search of plant matter, using their long necks to reach high or sweep low depending on feeding strategy.

Yet, despite their size and importance, the fossil record of Middle Jurassic sauropods in China remains sparse—especially compared to the explosion of fossils from the Late Jurassic Morrison Formation in North America or the Tendaguru Beds of Tanzania. The few that are known—Shunosaurus, Datousaurus, Klamelisaurus—have all played crucial roles in reconstructing early sauropod evolution. But many are known only from partial skeletons, often missing the head.

The skull of Jinchuanloong niedu, therefore, fills a glaring gap in our understanding—not just of one species, but of a whole segment of sauropod history.

An Evolutionary Puzzle Piece

The significance of Jinchuanloong isn’t limited to its completeness. It also helps clarify how early eusauropods diversified after the Early Jurassic extinction.

According to the authors, the mix of primitive and derived traits in Jinchuanloong illustrates a transitional phase in sauropod evolution. Its skull structure retains some ancestral features found in earlier sauropodomorphs, but also displays innovations that foreshadow later neosauropods.

This “mosaic evolution”—where different parts of the anatomy evolve at different rates—is a recurring theme in dinosaur evolution. It challenges the idea of linear progress, suggesting instead a complex, branching path with many experiments along the way.

In this case, Jinchuanloong appears to have been an evolutionary “cousin” to the main sauropod line that would lead to the famous giants of the Jurassic and Cretaceous. But it also represents a distinct ecological strategy, potentially occupying a different niche in the food web of its time.

Implications for Paleobiogeography

One of the big questions in dinosaur paleontology is how species moved and diversified across the ancient supercontinents. During the Jurassic, what is now China was part of Laurasia, a northern landmass that included much of modern-day Asia and Europe. The presence of a basal eusauropod like Jinchuanloong in northwest China raises intriguing questions about regional endemism and dispersal.

Did East Asia harbor its own lineages of early sauropods, evolving in relative isolation? Or did these animals migrate across wide corridors of connected habitats? The answer likely lies somewhere in between. The researchers note that Jinchuanloong shares traits with both East Asian taxa like Shunosaurus and European forms like Turiasaurus, suggesting a complex web of evolutionary relationships stretching across continents.

More discoveries will be needed to untangle these patterns, but Jinchuanloong provides a crucial new data point—both geographically and phylogenetically.

More Than Just Bones: A Glimpse into Deep Time

Paleontology is often a story of absence—of things lost, crushed, scattered by time. But occasionally, a find like Jinchuanloong niedu comes along and illuminates a whole hidden corner of the past. It is a reminder that even after 150 years of dinosaur discovery, there are still gaps in our knowledge large enough to walk a sauropod through.

The nearly complete skull alone is worth the excitement. But it’s the context—the age, the location, the evolutionary positioning—that makes this specimen a cornerstone for future research.

The authors of the study, published in Scientific Reports, put it best: “The discovery of Jinchuanloong niedu enriches the diversity of early diverging sauropods and provides additional information to help understand the evolutionary history of sauropods in northwest China.”

In other words, this isn’t the end of the story. It’s the beginning of a new chapter.

The Long Reach of the Jinchuan Dragon

If you stood beneath Jinchuanloong niedu 165 million years ago, you’d likely feel dwarfed by its presence. Ten meters long, head craning above the treetops, tail slicing the air in slow arcs—it would have looked like a moving bridge between heaven and earth. And in a way, it still is.

Today, Jinchuanloong bridges gaps in time, in anatomy, in evolution. It links the basal sauropods of the Early Jurassic to the titans of the Late Jurassic. It connects isolated fossil finds into a more coherent picture of dinosaur history. And it ties modern researchers to a lineage of discovery that stretches back to the very dawn of paleontology.

Somewhere in the hills of Gansu, layers of stone still wait to give up their secrets. Perhaps another dragon slumbers beneath the surface, waiting for science to find it. Until then, Jinchuanloong niedu stands as both a beacon and a challenge—a whisper from the deep past, telling us there is always more to learn.

Reference: Ning Li et al, A new eusauropod (Dinosauria, Sauropodomorpha) from the Middle Jurassic of Gansu, China, Scientific Reports (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41598-025-03210-5