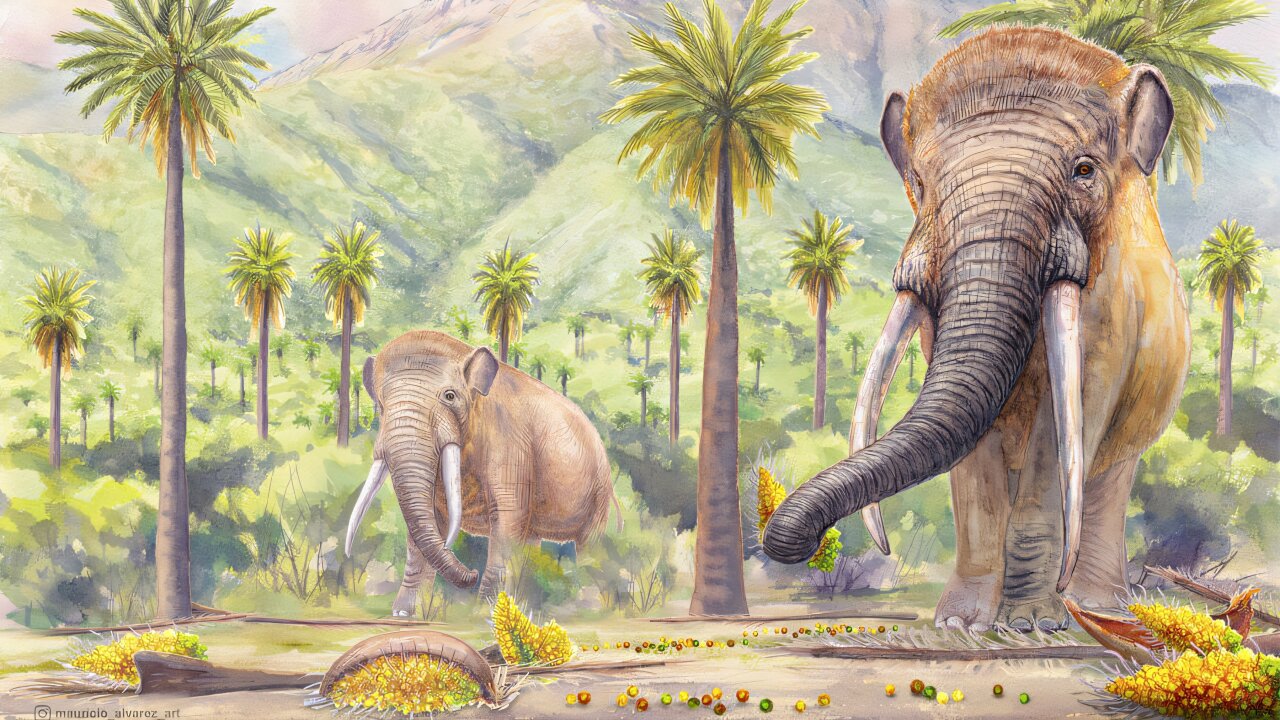

Ten thousand years is a long time to miss someone. But in the ancient forests of South America, the absence of one creature still echoes in the shape of leaves, the spread of trees, and the quiet vanishing of fruits that once flourished. That creature was Notiomastodon platensis, a now-extinct relative of the elephant—and as a groundbreaking new study reveals, its disappearance was not just zoological. It was ecological, botanical, and evolutionary.

In a landmark discovery that connects paleontology to modern conservation, scientists have found the first direct fossil evidence that these South American mastodons consumed fruit regularly and played a vital role as seed dispersers—an ecological function that has remained irreplaceable for millennia.

The study, published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, was led by Erwin González-Guarda of the University of O’Higgins in Chile, with major contributions from the Catalan Institute of Human Paleoecology and Social Evolution (IPHES-CERCA). It confirms a long-standing ecological theory with real, physical traces—etched in ancient molars, locked in the calculus of time.

The ghosts that fed the forest

The idea that extinct megafauna once spread seeds across vast distances isn’t new. In 1982, biologist Daniel Janzen and paleontologist Paul Martin proposed the “neotropical anachronisms” hypothesis: that large fruits evolved in partnership with massive animals like mastodons, who ate them whole and excreted their seeds far from the parent tree. The theory was elegant—but lacked one crucial element: fossil proof.

Now, for the first time, that missing evidence has surfaced.

Analyzing 96 fossilized mastodon teeth spanning more than 1,500 kilometers of Chilean landscape—from the arid coast of Los Vilos to the temperate forests of Chiloé Island—researchers discovered clear evidence of fruit consumption. Microscopic wear patterns on teeth, stable isotope signatures, and fossilized dental plaque (yes, even ancient mastodons had tartar buildup) revealed traces of starch grains and plant tissues associated with large, fleshy fruits.

One standout example? The Chilean palm (Jubaea chilensis), a towering tree whose bulbous, sugary fruits now rot unconsumed beneath its aging canopy.

“These are not just incidental findings,” says Florent Rivals, ICREA research professor at IPHES-CERCA. “We’re seeing a pattern—mastodons were fruit lovers. And that made them forest architects.”

From ancient mouths to modern extinction

Beneath the scientific excitement lies an unsettling truth: the mastodons are gone, and so is the role they played. The forests that once depended on them for seed dispersal have changed—and not for the better.

When mastodons roamed, they crunched fruits whole and walked long distances. Their gut chemistry scarified seeds, preparing them for germination. Their massive size and range meant that trees could scatter their offspring across vast regions, promoting genetic diversity and forest expansion.

Now, with those long-traveled seeds no longer in motion, many trees have lost their most efficient ally.

“We’re witnessing the long tail of an ancient extinction,” explains study co-author Andrea P. Loayza. “These trees evolved with partners. Without them, they’re struggling.”

Using machine learning models, the researchers mapped the conservation status of fruiting plants that once relied on megafauna like mastodons. In central Chile—where no large seed-dispersing animals remain—40% of these plant species are now threatened, a figure four times higher than in tropical zones where animals like monkeys or tapirs still fulfill that role.

The legacy written in teeth

The study’s core strength lies in its “multiproxy” approach. Fossil teeth, often overlooked as relics of chewing, became time capsules. The research team used three complementary techniques to paint a complete picture:

- Stable isotope analysis, which decodes the chemical makeup of fossilized enamel, revealing what the animal ate and the ecosystem it inhabited.

- Microwear texture analysis, which examines microscopic scratches and pits, showing whether the diet included soft fruits or tougher foliage.

- Dental calculus analysis, in which fossilized plaque is dissolved and examined for plant residues.

“In one tooth, you might find evidence of a forest’s entire history,” says Carlos Tornero, professor at the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona and expert in stable isotopes. “And in many teeth, you find the story of a vanished relationship between plant and animal.”

Perhaps the most emblematic discoveries came from the Lake Tagua Tagua site in the O’Higgins Region—a Pleistocene treasure trove long known for its fossil richness. Here, the teeth of Notiomastodon platensis held not only the signature of fruit but also a snapshot of a vanished ecosystem: a moist, fruit-rich forest traversed by trunked giants.

Living fossils in silent forests

Today, the Chilean palm (Jubaea chilensis), the monkey puzzle tree (Araucaria araucana), and the gomortega (Gomortega keule) still cling to survival. But they are relics of a world that no longer exists.

The Chilean palm’s fruits are too large for any modern animal to eat and disperse effectively. The monkey puzzle’s seeds were once likely carried in the bellies of extinct herbivores. The gomortega, critically endangered, produces large drupes with no modern disperser to spread them.

“These species didn’t just evolve in isolation,” says Alia Petermann-Pichincura, co-author and researcher on the project. “They evolved in dialogue—with animals, with climate, with landscape. When you break that dialogue, the forest falls silent.”

Fragmented populations. Limited seed spread. Low genetic diversity. These are the consequences of ecological ghosts.

Why it matters now

In a world focused on immediate crises, it can be hard to see the relevance of a vanished elephant-cousin that lived before recorded history. But this research makes it clear: understanding the past isn’t academic nostalgia—it’s a mirror reflecting our future.

“Paleontology isn’t just about bones and ancient worlds,” says Rivals. “It helps us see what we’ve lost—and what we still might recover.”

As the climate crisis accelerates and biodiversity continues to decline, restoring lost functions in ecosystems becomes an urgent goal. Some conservationists now discuss the concept of rewilding—reintroducing large animals to replicate extinct ecological roles. Could living elephants, in carefully controlled environments, help disperse the seeds of endangered trees? Could humans take up the role, planting seeds where mastodons once walked?

These are big, complex questions. But one thing is clear: ecosystems are not static. They’re conversations across species, across time. And when one voice goes silent, the entire system falters.

A whisper from deep time

What do we owe the past? Perhaps it is not about returning to what once was, but understanding why it mattered. The mastodons, in their slow and gentle march through ancient forests, were gardeners of the wild. Their footprints carried seeds. Their appetites shaped landscapes.

They are gone. But the traces of their passage—held in teeth, in trees, in the narrowing diversity of forgotten fruits—remain.

And thanks to this extraordinary study from the University of O’Higgins and its international partners, we now have a clearer view of that ancient world—and a sharper warning about our own.

In the calculus of extinction, no loss is ever singular. One vanished species leaves behind a web of unraveling connections. And sometimes, it takes a scientist’s gaze, a fossilized tooth, and a long memory to hear what the forest has been trying to say for ten thousand years.

Reference: Erwin González-Guarda et al, Fossil evidence of proboscidean frugivory and its lasting impact on South American ecosystems, Nature Ecology & Evolution (2025). DOI: 10.1038/s41559-025-02713-8