In the heart of China’s parched Tarim Basin, beneath the lifeless sands and blazing skies, lies a story as haunting as it is enigmatic. Wooden boats, buried deep in the desert, cradle the remains of an ancient people—lost to time, yet whispering through their graves. This is the Xiaohe culture, a Bronze Age civilization whose funerary rituals continue to puzzle archaeologists almost 4,000 years after their last burial.

Now, in a striking reappraisal of their symbolic world, Swiss archaeologist Dr. Gino Caspari is reshaping how we interpret these spectral echoes of the past—not just as archaeological data, but as cultural poetry carved in sand, wood, and bone.

A Graveyard Like No Other

When Swedish explorer Folke Bergman stumbled across the Xiaohe site in 1934, even he may not have fully grasped the importance of what lay beneath the dust. Near the Lop Nur salt lake in what is now Xinjiang, China, the site contained graves that seemed to float in time—preserved like museum pieces by the hyperarid desert climate.

Bergman managed to excavate only 12 graves before political tides and logistical difficulties swept further investigation away for nearly 70 years. It wasn’t until the early 2000s that a full excavation resumed under the supervision of the Xinjiang Institute of Archaeology. Their findings were as remarkable as they were perplexing.

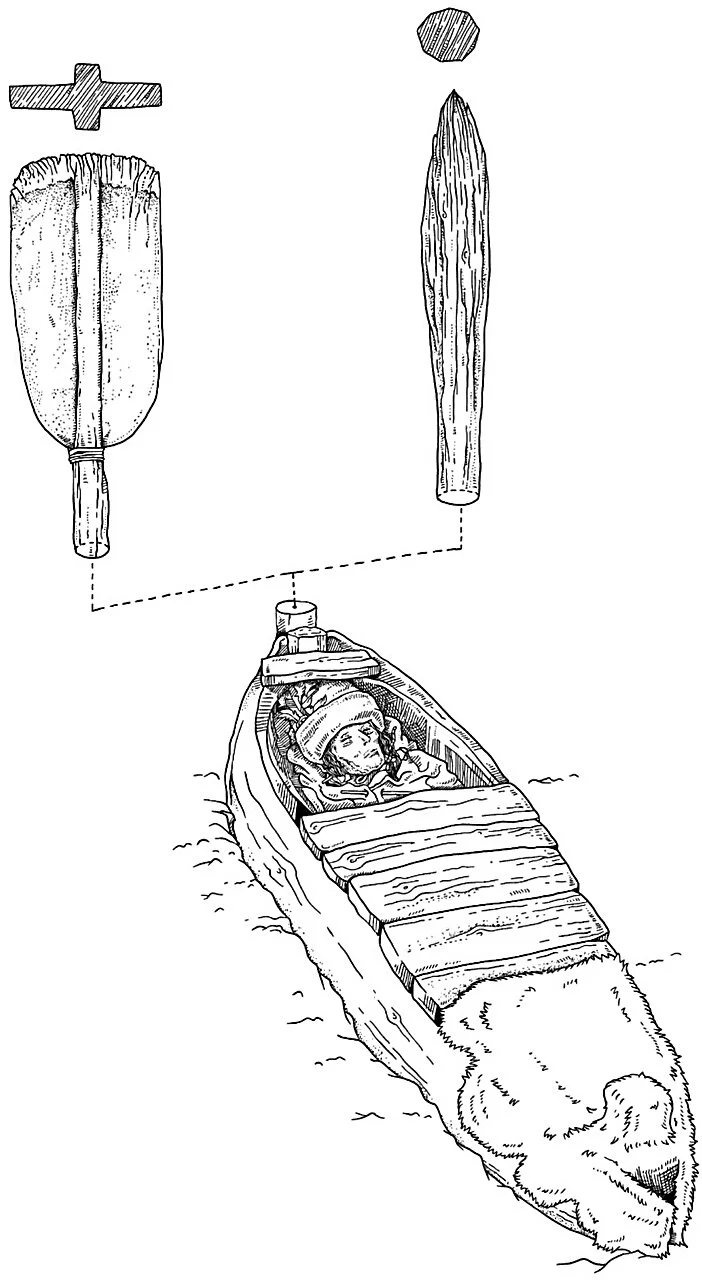

More than 167 graves were uncovered—boat-shaped wooden coffins, human remains wrapped in cattle hides, and towering upright poles, some painted in red, others carved into sensuous ovals. Amid these surreal burials, one message seemed clear: the Xiaohe culture held a deep and symbolic connection to water, death, and the animal world. But what it all meant was anyone’s guess.

Drifting in Symbolism, Anchored in the Desert

Enter Dr. Gino Caspari. Armed with decades of experience studying Central Asian prehistory and an instinct for finding patterns in ancient ritual, Caspari’s recent work delves into the forgotten metaphors of the Xiaohe dead.

“The funerary ritual is completely different from the surrounding cultures,” he says. “And that is part of the fascination of this culture.”

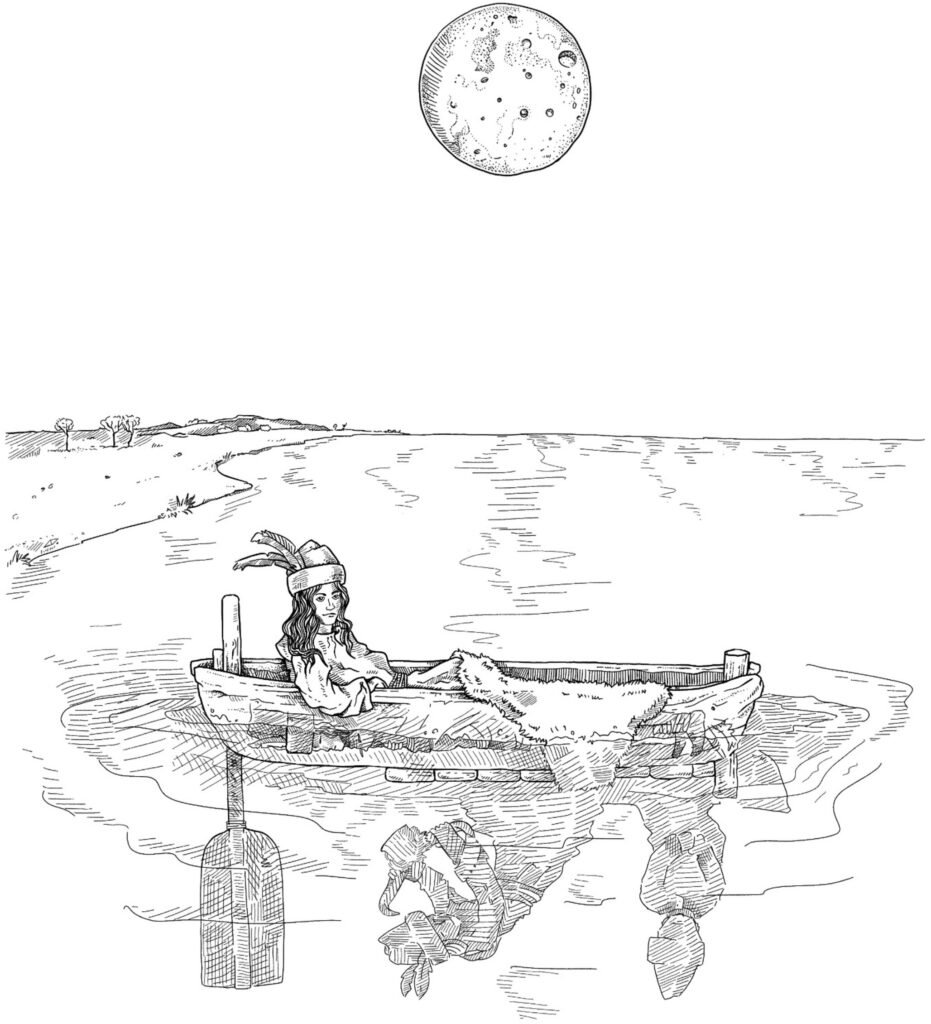

The coffin design was especially compelling. Long, narrow, often with flat bases, these burials had the unmistakable shape of boats or canoes—yet there was no body of water in sight. Or was there?

To understand the Xiaohe, Caspari argues, one must understand the landscape they lived in—not a static desert, but a dynamic ecosystem shaped by seasonal rains and oasis waters. Though surrounded by desert, the Tashkurgan Basin, where Xiaohe once thrived, was periodically transformed into a wetland refuge. It was this water—scarce, life-giving, and unpredictable—that may have inspired the most intimate aspects of their mortuary customs.

Paddles or Phalluses? Rethinking the Ritual Poles

Among the most debated features of Xiaohe graves are the towering poles planted at the heads of the coffins. Some are blunt and oval-shaped, others capped in red paint or stylized with more pointed ends. Earlier interpretations leaned toward overt sexual symbolism—phallic and vulval motifs meant to invoke fertility, gender, or rebirth.

But Dr. Caspari is not so sure.

“The association between pole type and biological sex doesn’t always hold,” he notes. In some cases, what was thought to be a “phallic” pole accompanied a female burial, and vice versa. This inconsistency raised a crucial question: Were researchers projecting symbolic categories onto a culture whose worldview might be altogether different?

Caspari proposes an alternative view: what if these poles weren’t phallic at all, but functional metaphors—representations of paddles and mooring posts, symbols from a water-bound cosmology? If the coffin is a canoe, then what would a canoe need to navigate the afterlife? Paddles to guide it, and posts to anchor it.

In this new light, the entire grave is transformed. It becomes a vessel, not just of the body, but of the soul. A spiritual canoe, launched into the mirrored waters of the beyond.

Echoes of a Shared Human Mythology

The idea of water as the passage between life and death is ancient and widespread. Caspari points out that cultures as diverse as Ancient Egypt, Bronze Age Scandinavia, and prehistoric North America share eerily similar symbols. In Egyptian mythology, the deceased journey down the Nile-like river Duat. Scandinavian burials sometimes involved literal boats or ship-shaped stone arrangements. Native American rock art and Saharan carvings depict upside-down worlds—reflections of the living realm in the afterlife.

Could the Xiaohe have shared this same cosmic vision?

It’s not a far stretch. The Xiaohe were pastoralists and farmers who thrived between desert and water, life and scarcity. Cattle were central to their world—not just in daily life, but in death. Their hides lined the coffins. Their skulls capped ritual structures. In one unique burial—a rectangular tomb unlike any other—layers of cattle hide and skulls form a kind of totemic monument. No human bones were found there. Was it a cenotaph? A shrine? The meaning remains elusive.

What is clear is that the Xiaohe were deeply spiritual. Their rituals were deliberate, layered, and rich with symbolism. To die was not to vanish—it was to set sail.

Missing Pieces and Silent Graves

Despite the groundbreaking work, much about Xiaohe remains a mystery. Of the estimated 350 graves that once existed at the site, fewer than 200 have survived the ravages of time, and only a handful have been studied in depth. Much of the available documentation exists only in Chinese and has not been fully translated or analyzed.

“Apart from limited maps of the Xiaohe cemetery, the information is unfortunately still rather incomplete,” Caspari says. “We cannot really say very much about the overall patterns because we need to wait for our Chinese colleagues to fully publish the materials.”

This limitation is compounded by modern geopolitical tensions and restricted access to Xinjiang, even for Chinese researchers. The sands that preserved Xiaohe’s secrets so well may now keep them hidden indefinitely.

A Culture Lost, but Not Forgotten

By around 1400 BCE, the Xiaohe culture disappeared. No written records remain. No stories were passed down. Their legacy lies only in bones, wood, and sand. Why they vanished—whether due to climate change, migration, or internal collapse—remains one of archaeology’s unanswered questions.

“At this point, it would be mere speculation,” says Caspari. “We simply do not have the data… Xinjiang plays such an important role in our understanding of the dynamics of prehistoric Central Asia.”

Yet, what Xiaohe left behind may be more than enough to stir the imagination of the modern world. In their funerary customs, we glimpse a universal human yearning: to connect the living with the dead, to transform death into journey, and to find meaning in the passage.

In a time where ancient cultures are often seen as footnotes in a grand march toward civilization, Xiaohe reminds us that the human soul has always been poetic. Even without writing, even without cities, they built a language of death and memory as rich as any empire.

And so the boats lie still beneath the desert sun, silent vessels of a forgotten people, their paddles raised toward an upside-down sky.

Reference: Gino Caspari, Reflections on water: funerary practice and symbolism at the Bronze Age site of Xiaohe, Asian Archaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1007/s41826-025-00105-2