In the heart of the ancient Roman city of Pollentia on the sun-drenched island of Mallorca, Spain, a cesspit has told a story that no scroll or silver platter ever could. Buried just steps from the city’s bustling forum and forgotten for two millennia, the dark, rank shaft—known blandly as E-107—has brought light to a culinary contradiction: thrushes, the sweet-voiced songbirds lauded by Roman elites, weren’t just for aristocrats.

According to a new study from the Mediterranean Institute for Advanced Studies (UIB-CSIC), published in the International Journal of Osteoarchaeology, these birds were not the precious table jewels described in Roman literature, but rather quick, greasy, and common street fare—the ancient Mediterranean’s answer to fried chicken.

The study, led by zooarchaeologist Alejandro Valenzuela, cracks open the debate that has simmered for decades: was the Roman love affair with thrushes an elite indulgence or a widespread appetite?

The answer, it turns out, was hiding at the bottom of a Roman toilet.

Unearthing a Hidden Kitchen

Roman cesspits were more than just medieval plumbing. They were time capsules of everyday life—repositories of refuse, of broken objects and forgotten meals. The cesspit E-107 is no exception. Dug nearly four meters deep, it lies behind taberna Z, a modest food shop flanking Pollentia’s central forum.

“This wasn’t some palatial villa with a lavish banquet hall,” says Valenzuela. “This was a street-side joint where people grabbed a bite between errands or bought hot food to take home. What ended up in the pit was what people ate on the go.”

Between 10 BC and AD 30, the pit filled rapidly with nearly 4,000 animal bones, most from pigs and rabbits. But curiously, a significant share—165 bones—belonged to thrushes, making them the most abundant bird remains in the entire deposit.

That’s not something you’d expect if these birds were reserved only for the wealthy.

Thrushes in the Texts vs. the Trash

For generations, classical scholars leaned on Roman writers like Varro, Apicius, and Columella, who painted thrushes as epicurean indulgences. There were references to specialized aviaries where birds were fattened on figs, markets where they fetched high prices, and feasts where they were served stuffed, roasted, or wrapped in pastry.

In the elite imagination, thrushes were the food of senators and emperors—not something one devoured standing in a public square.

But archaeology often offers a reality check.

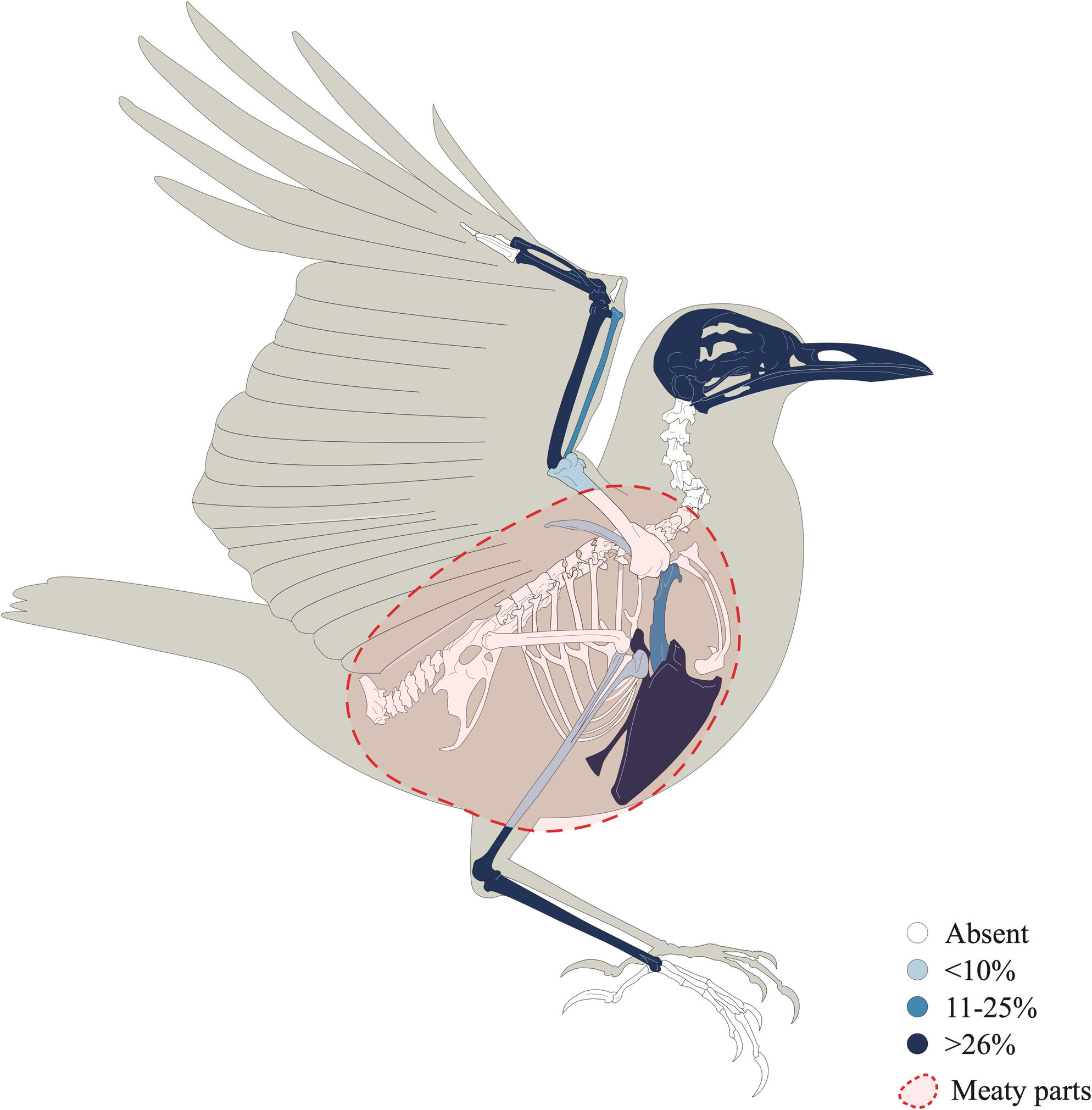

What Valenzuela and his colleagues found in the cesspit tells a different tale. The bird bones weren’t discarded whole, nor were they singed by fire or marked by teeth. They had been butchered efficiently, with meat-rich parts—humeri, femora, and coracoids—suspiciously missing.

“The pattern was striking,” Valenzuela explains. “What we found were mostly wings, heads, and lower legs—scraps left after the meaty parts had been removed, likely cooked and eaten nearby. This wasn’t garbage from a noble feast. This was fast food.“

Biometrics and Bird Bits

Identifying the species required precision. Many small birds look similar when reduced to broken bones. Using morphological and biometrical analysis, the team compared wing and leg bones—particularly the carpometacarpus, ulna, and tarsometatarsus—to modern reference samples.

Their findings were definitive: the bones matched Turdus philomelos, the modern song thrush, a small migratory bird known for its rich, fluting calls.

And just like today, these birds migrated en masse to the Mediterranean in winter—likely making them seasonal specials in the ancient menu of Pollentia.

The Street-Food Economy of a Roman City

One clue to the birds’ culinary journey lies in taberna Z itself. The shop was equipped with an embedded amphora counter—a common feature in Roman eateries that acted as both a display and a heat source for ready-to-serve food.

The presence of thrush remains in the cesspit just behind this counter suggests a vivid scene: songbirds, probably trapped in bulk during the winter migration, were butchered quickly, flattened, and flash-fried for hungry passersby.

“It’s entirely plausible that these birds were skewered or pan-fried right on the spot,” Valenzuela says. “The absence of certain bones and the lack of burning supports this idea—these weren’t long-cooked delicacies, they were fast, hot, and probably delicious.”

It’s a picture that upends conventional wisdom. Roman cities weren’t just theaters of elite indulgence. They had their own vibrant street-food culture—one that catered to all social classes, offered seasonal variety, and capitalized on nature’s bounty.

From Gourmet Myths to Everyday Meals

The Pollentia cesspit invites us to rethink how we imagine ancient diets.

Historians often lean heavily on texts, and Roman authors, being elite men themselves, naturally focused on elite experiences. Their descriptions of food skew toward the extravagant—peacocks stuffed with other birds, dormice glazed with honey, thrushes raised like foie gras.

But garbage tells a more democratic story.

“This is the beauty of bioarchaeology,” Valenzuela notes. “Bones don’t lie. They aren’t written to impress or sell a narrative. They just accumulate, layer by layer, telling us what people really ate and how they lived.”

And in this case, the layers speak of common thrush consumption—not in palaces, but in public squares, served hot to the Roman everyman.

Why This Matters Today

The discovery might seem niche—a few bird bones in an old pit—but it speaks to broader questions that still resonate today. Who gets to tell the story of a civilization? What are the blind spots in our sources? How do class, geography, and seasonality shape our food systems?

Even in modern societies, the divide between “gourmet” and “everyday” food often masks a more complex reality. Dishes that once fed the poor—like sushi in Japan or tacos in Mexico—can become luxurious in the right social context. The thrush bones of Pollentia are a reminder that food culture is always layered, always shifting, and always worth a closer look.

And perhaps there’s something timeless about the appeal of simple, flavorful food cooked quickly and eaten on the street.

A Cesspit’s Quiet Testimony

Two thousand years ago, in a city carved by Roman ambition, someone stood beside a taberna and paid a few coins for a hot, crispy bird. Today, we call it fast food. Back then, it was just lunch.

In the end, the cesspit spoke when the scrolls stayed silent. Its dark, dank contents illuminated a side of Roman life that literature had obscured. It revealed not just what people ate, but who they were—their habits, their economies, and their daily decisions.

For Alejandro Valenzuela and his team, it was a breakthrough. For the rest of us, it’s a poignant reminder: history doesn’t just live in monuments or museums. Sometimes, it lives in the trash.

Reference: Alejandro Valenzuela, Urban Consumption of Thrushes in the Early Roman City of Pollentia, Mallorca (Spain), International Journal of Osteoarchaeology (2025). DOI: 10.1002/oa.3416