Beneath the quiet soil of deserts, beneath the cold shadows of cliffs, and deep within the sedimentary layers of forgotten oceans lies a secret history—etched not in ink, but in stone. Fossils are more than bones. They are whispers from the past, records of vanished worlds, chronicles of evolution, extinction, and survival. For those who know where to look, the Earth becomes a living museum, one whose exhibits stretch back billions of years.

Some places on Earth are especially rich in these ancient clues. They are not just geologic formations; they are time capsules, holding within them the memory of ecosystems long vanished. These famous fossil sites help scientists reconstruct how life on Earth has changed—how sea creatures first dared to crawl onto land, how dinosaurs reigned and fell, and how early humans first walked upright.

Let us journey across continents, through forests, deserts, and cliffs, to visit the fossil sites that have changed our understanding of life on Earth forever. These places are not only scientifically significant—they are hauntingly beautiful in their own way, steeped in deep time and echoing with ancient life.

The Burgess Shale: A Cambrian Dreamscape in Canada

High in the Canadian Rockies, where alpine meadows bloom and glaciers feed turquoise lakes, lies a fossil site that captures one of the most enigmatic moments in Earth’s history: the Cambrian Explosion. Over half a billion years ago, life underwent a dramatic transformation. Within a relatively short time, in geologic terms, most major animal groups appeared.

Discovered in 1909 by Charles Doolittle Walcott, the Burgess Shale in British Columbia preserves incredibly detailed fossils of soft-bodied marine creatures that would not normally fossilize. Here, ancient oceans teemed with strange beings—Opabinia with five eyes and a clawed proboscis, Hallucigenia walking on spiked legs, and Wiwaxia armored in scales and spines.

What makes the Burgess Shale so astonishing is not just the age of the fossils—about 508 million years—but the window it provides into the early complexity of animal life. These creatures represent evolutionary experiments, many of which left no descendants. The site forces us to consider the contingency of evolution: had events unfolded differently, perhaps creatures like Opabinia, not humans, might have inherited the Earth.

The Burgess Shale whispers of a world before vertebrates, before bones, before even land plants. It is one of the most important paleontological sites ever discovered, and it remains a pilgrimage site for scientists who wish to understand life’s earliest blueprint.

La Brea Tar Pits: Death Traps in the Heart of Los Angeles

In the middle of one of the world’s busiest cities, traffic swirls around Wilshire Boulevard, and skyscrapers cast long shadows—but below the surface lies a time capsule of the Ice Age. The La Brea Tar Pits in Los Angeles are one of the most remarkable fossil sites on Earth, preserving thousands of years of life in a natural asphalt trap.

These tar pits, or more accurately, asphalt seeps, have been active for tens of thousands of years. Animals drawn to the smell of water or a struggling prey would become mired in the sticky substance. Predators would follow—and they too would be trapped. What resulted was a mass graveyard that spans millennia.

The fossil record here is staggering: over 3.5 million fossils have been recovered. They include sabertooth cats, dire wolves, mammoths, ground sloths, American lions, and even the occasional human. Tiny bones of insects and birds are preserved alongside massive mammal skulls. La Brea gives us a detailed look into the ecosystems of Ice Age North America.

But beyond the sheer volume of fossils, the site offers something rare: a dynamic picture of predator-prey relationships, climate change, and extinction events that shaped the continent just before humans began to settle it. It is one of the few places where the drama of an ancient ecosystem plays out scene by scene, like a black-and-white silent film, projected in stone.

Solnhofen Limestone: Preserving the Feathered Past in Germany

In the limestone quarries of Bavaria, Germany, lies one of paleontology’s most prized possessions: Archaeopteryx, the so-called “first bird.” Discovered in the 1860s, this creature had feathers like a bird, but teeth, claws, and a long bony tail like a reptile. It was a transitional fossil—a bridge between dinosaurs and modern birds—and it rocked the scientific world.

The Solnhofen limestone was once a shallow tropical lagoon during the Late Jurassic, about 150 million years ago. The lagoon’s highly saline, low-oxygen waters prevented decay and scavenging, allowing exceptional preservation of delicate creatures. Here, even soft tissues—feathers, skin, internal organs—could be fossilized in exquisite detail.

Besides Archaeopteryx, the site preserves a stunning diversity of ancient life: pterosaurs with 10-foot wingspans, delicate jellyfish, armored crustaceans, and even fish caught mid-swim. It’s a place where evolutionary biology and fine art converge—each fossil is a masterpiece carved by time itself.

Solnhofen reminds us that evolution is not a straight line, but a tangled tree. The discovery of feathered dinosaurs here helped confirm that birds are not separate from dinosaurs—they are living dinosaurs. This site didn’t just change our understanding of birds—it reshaped our entire view of what it means to fly.

Liaoning Province: China’s Feathered Revolution

In northeastern China’s Liaoning Province, layers of volcanic ash have entombed one of the richest fossil deposits in the world. Known as the Jehol Biota, these Early Cretaceous sediments—dating back 120 to 130 million years—preserve an extraordinary array of life, including some of the most spectacular feathered dinosaurs ever discovered.

This site has rewritten the book on dinosaur evolution. It was here that fossils of Sinosauropteryx, Microraptor, and Yutyrannus were unearthed—dinosaurs with clear evidence of feathers, not just for flight but also insulation and display. Some had wings on both arms and legs; others showed color patterns. These fossils closed the gap between birds and their dinosaur ancestors.

But Liaoning is not just about dinosaurs. It also preserves fish, mammals, amphibians, insects, and plants in such remarkable detail that even stomach contents and muscle fibers can sometimes be observed. It’s as if an entire ecosystem was flash-frozen in time.

What makes the Liaoning fossils so emotionally resonant is their fragility. Many of these creatures died in volcanic eruptions, ashfalls, or toxic lakes—catastrophic ends that froze moments of life and death forever. It is a fossil Pompeii, where nature’s violence gave rise to a treasure of evolutionary history.

The Karoo Basin: Chronicles of Extinction in South Africa

In South Africa’s Karoo Basin, the arid landscape stretches for miles beneath a sky that has seen more than one end of the world. Here lie fossils that document a period of profound evolutionary transformation—and the worst mass extinction in Earth’s history.

The Karoo’s sedimentary rocks preserve the story of the Permian-Triassic extinction event, which occurred about 252 million years ago. During this cataclysm, more than 90% of marine species and 70% of terrestrial vertebrates perished. The world changed—radically and irreversibly.

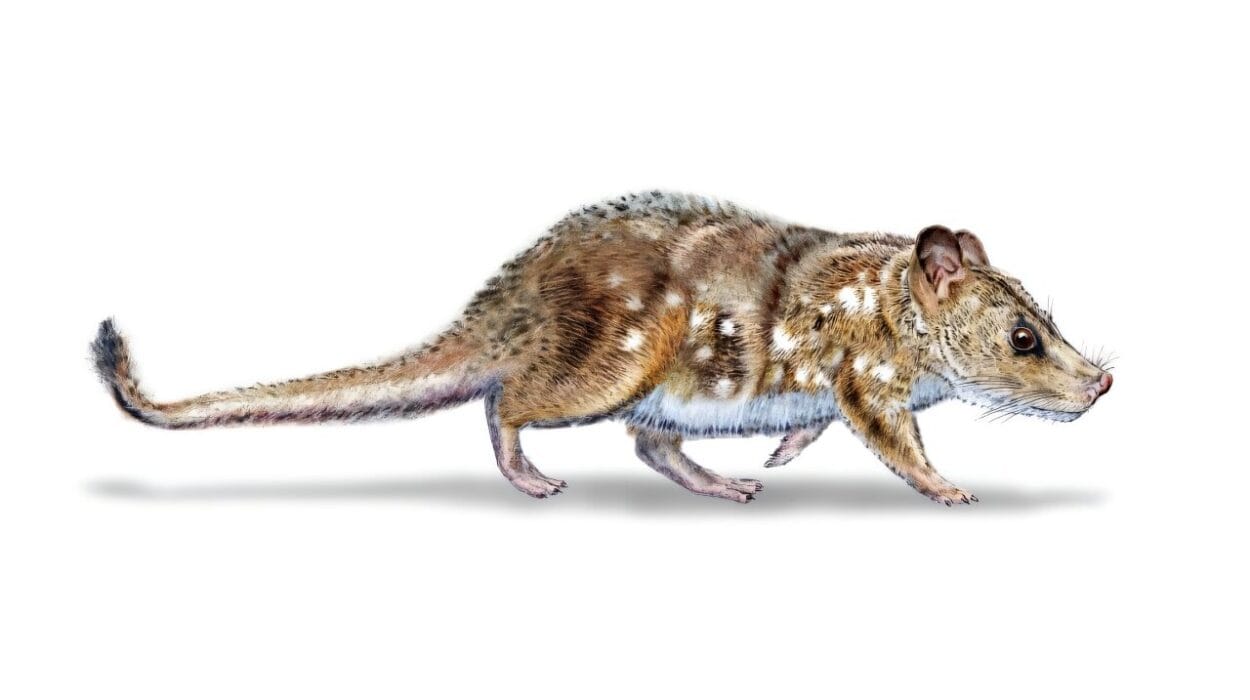

Among the fossils here are synapsids—mammal-like reptiles such as Lystrosaurus, which survived the extinction and became one of the most common animals in the Early Triassic. The fossils show a progression from the reptilian ancestors of mammals toward more advanced forms with differentiated teeth, larger brains, and more upright postures.

The Karoo is not a place of flashy fossils or Hollywood-famous species. Instead, it is a site of transition—a geologic record of resilience and rebirth. It shows that life, even after catastrophe, finds a way. For paleontologists, it is one of the most important records of deep-time ecological recovery, and its lessons are more relevant than ever in an age of biodiversity loss.

The Messel Pit: A Snapshot of an Ancient Rainforest

Near Frankfurt, Germany, lies a quarry so rich in fossils that it seems like a prehistoric film reel. The Messel Pit was once a volcanic lake, and about 47 million years ago during the Eocene epoch, it was surrounded by a lush rainforest teeming with life.

Fossils from Messel are preserved with astonishing fidelity—fur, feathers, skin, even stomach contents are often intact. Among the discoveries are early horses the size of dogs, primates with nails instead of claws, giant ants with wingspans like butterflies, and birds that had already evolved features like perches and strong beaks.

Messel is particularly significant for understanding mammalian evolution. It captures a world after the dinosaurs, where mammals were rising to dominance, adapting to every ecological niche. It also gives insight into the origin of bats, snakes, and even some early carnivores that resemble modern raccoons and cats.

The Messel Pit doesn’t just show skeletons—it shows behavior, environment, even tragedy. Fossils of turtles mid-copulation and fish with prey still in their throats reveal lives cut short in an instant. For scientists, it’s like stumbling upon nature’s own documentary—frame by frame, in stone.

Dmanisi: Georgia’s Gateway to Humanity

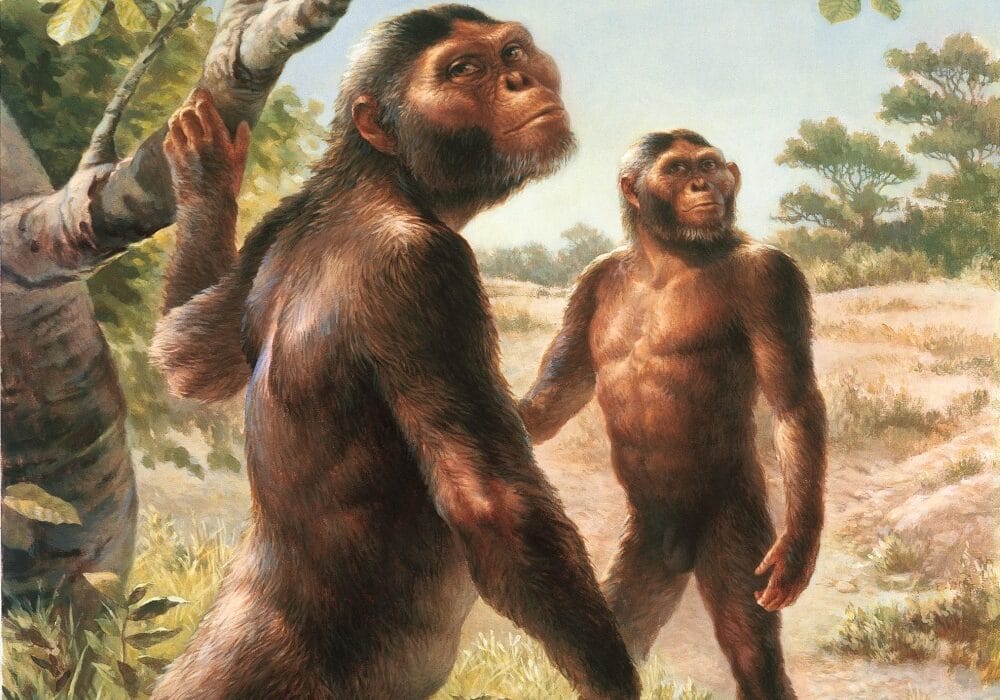

In the hills of Georgia, near the town of Dmanisi, an archaeological site began to yield secrets that would shake the foundations of human evolutionary theory. Between 1991 and 2005, researchers uncovered the oldest known hominins outside Africa—dating back 1.8 million years.

These early human ancestors, classified as Homo erectus or possibly a variant species called Homo georgicus, had small brains but walked upright and used tools. Their presence in Eurasia at such an early date challenges previous models that humans left Africa much later and with more advanced anatomy.

The fossils include skulls of multiple individuals, ranging in age, sex, and size. Remarkably, one skull belonged to a toothless elderly individual, suggesting that others may have cared for him. This hints at the beginnings of social cooperation—a hallmark of later human evolution.

Dmanisi isn’t just a fossil site. It’s a doorway into one of humanity’s greatest mysteries: why we left Africa, how we adapted, and what it means to be human. It brings the story of migration and survival into sharp focus and underscores that our ancestors were far more capable than once believed.

The Green River Formation: Fish Fossils and Fossilized Drama

In the high desert regions of Wyoming, Utah, and Colorado, the Green River Formation tells the story of ancient freshwater lakes that once rippled through a subtropical paradise. Dating back about 50 million years, this site preserves one of the world’s most complete records of fossilized freshwater fish.

Lush with fossilized plants, turtles, insects, birds, and fish, the Green River Formation is a testament to the quiet power of sedimentation. Over millions of years, thin layers of limestone, shale, and mudstone built up, entombing fish in situ—sometimes in the middle of a chase, a strike, or a death struggle.

Among the most famous finds is the Knightia, a small schooling fish and Wyoming’s state fossil. But the site also preserves gars, rays, eels, and giant freshwater predators, painting a vivid picture of predator-prey dynamics in ancient lakes.

The Green River fossils aren’t just beautiful; they’re scientifically vital for studying climate, ecosystem change, and vertebrate evolution in the Eocene. Their delicate details—fin rays, scales, gut contents—provide a precision that is rare in the fossil record.

The Grand Staircase and Morrison Formation: Dinosaurs of the American West

In the American West, where red rock canyons stretch across Utah, Colorado, Wyoming, and New Mexico, lies one of the richest dinosaur treasure troves in the world: the Morrison Formation. Dating from the Late Jurassic, about 150 million years ago, this rock unit has yielded an all-star cast of dinosaurs.

Here lived the giants: Stegosaurus with its plated back, Apatosaurus with its whip-like tail, and Allosaurus, the top predator of its time. The bones, often found in bonebeds, show signs of water transport and scavenging, revealing complex ecosystems.

Further south, in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, new species of dinosaurs continue to be uncovered, including horned ceratopsians, duck-billed hadrosaurs, and unique tyrannosaurs. These finds are helping paleontologists understand the end of the Age of Dinosaurs and how ecosystems responded to changing sea levels and climates.

What makes the Morrison Formation so emotionally captivating is the sheer scale of life it reveals—herds of giants roaming floodplains, forests echoing with calls, and rivers pulsing with life. It’s not just about dinosaurs—it’s about the world they built and left behind.

Fossil Sites as Time Machines

Every fossil site is a doorway into a vanished world. Each tells a different part of Earth’s story: the explosion of life, the death of ecosystems, the rise of mammals, the dawn of humanity. These places allow us to walk alongside creatures that vanished millions of years ago, to touch the bones of our ancestors, and to witness the Earth’s astonishing capacity for change.

Fossils do more than inform—they inspire. They connect us to the deep time of our planet, reminding us that life is resilient, adaptable, and often surprising. But they also caution us: extinction is real, and the ecosystems we take for granted today could become tomorrow’s fossils.

To preserve these sites is to preserve our past—and, perhaps, our future. As long as we continue to dig, to ask, and to wonder, these ancient places will speak to us. Their voices are faint but enduring, etched in the very bones of the Earth.