For over a century, paleontologists have stared into the fossilized faces of dinosaurs, trying to imagine what their lives might have been like. We can estimate their size, their diets, even their colors through modern science—but one mystery has stubbornly resisted all efforts: their sex. How do you tell a male dinosaur from a female when millions of years have stripped away every trace of soft tissue? Without reproductive organs, the bones alone rarely tell a clear story. Yet, a new study suggests that perhaps the answer has been hiding in plain sight—in the scars of ancient intimacy.

A Trail of Clues in Stone

Hadrosaurids, the gentle giants often called duck-billed dinosaurs, were among the most social creatures of the Cretaceous Period. They roamed ancient floodplains in massive herds, their flat, duck-like snouts perfect for stripping vegetation. But buried deep within their fossilized skeletons lies an unexpected clue to their private lives.

For decades, paleontologists noticed a curious pattern in the middle section of hadrosaurid tails—long, bony spikes called neural spines often showed signs of healed fractures. These were not isolated accidents; they appeared again and again, across specimens found in North America, Europe, and Asia. Why did so many hadrosaurs break their tails in the same way?

Some researchers suggested that the dinosaurs might have trampled one another in crowded herds. Others proposed that males fought each other for dominance, as modern-day deer or giraffes do. But none of these ideas fully fit the evidence. The fractures were too consistent, too neatly located. There had to be another explanation—one that went beyond mere accident or aggression.

Reconstructing a Prehistoric Mystery

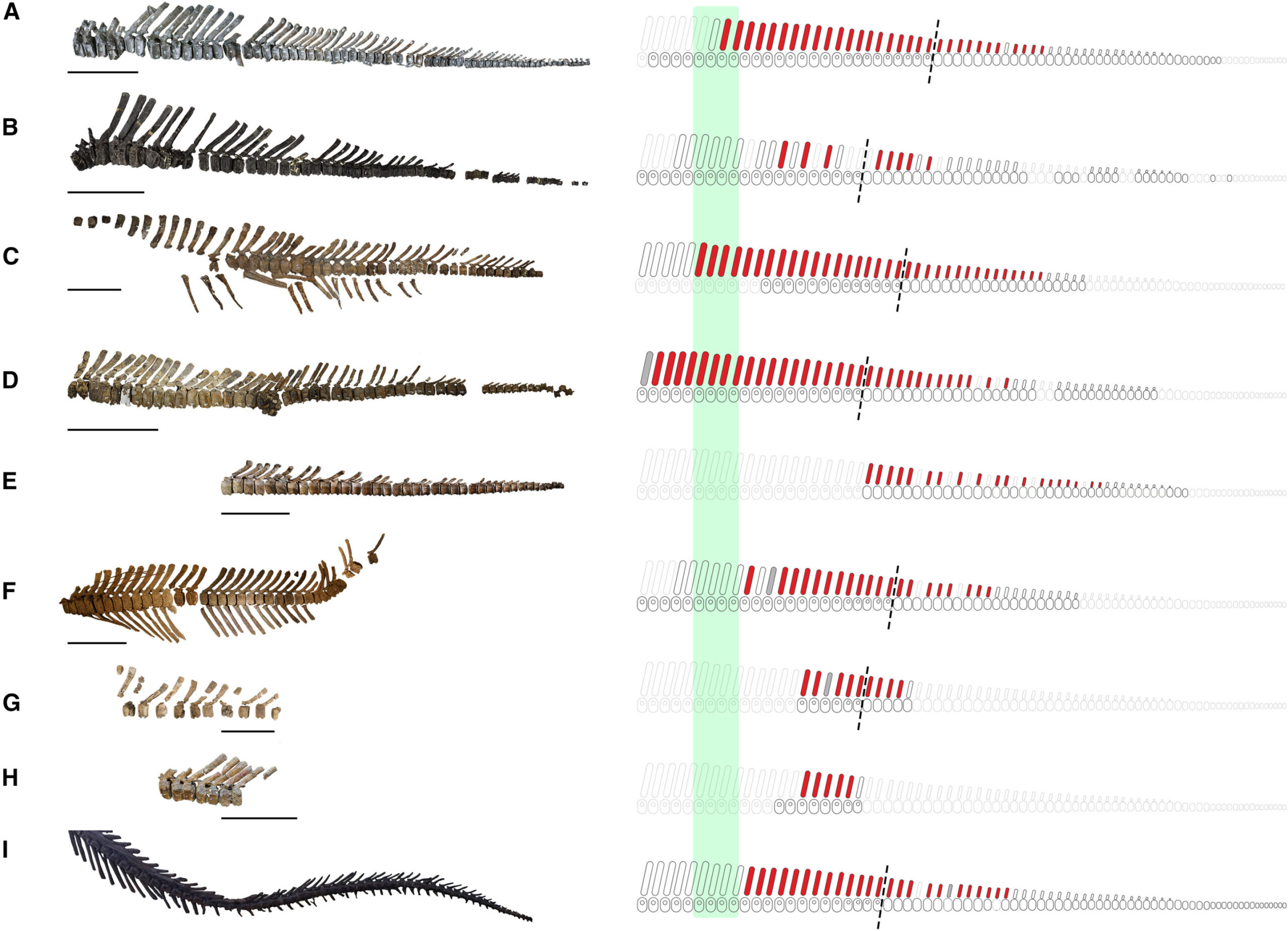

To solve this ancient puzzle, a team led by Dr. Filippo Bertozzo at the Royal Belgian Institute of Natural Sciences took a fresh look. They gathered data from 551 tail spines belonging to various hadrosaur species, representing fossils from multiple continents and time periods. Using advanced 3D modeling and computer simulations, they recreated the structure of the hadrosaur tail in astonishing detail.

Then, they virtually applied different kinds of forces to see what might cause the pattern of breaks seen in the fossils. The results were clear and surprising. Only one kind of pressure—a diagonal weight pressing down at an angle of 30 to 60 degrees—matched the fossil damage perfectly. That angle, it turned out, corresponds precisely to the position and weight distribution of a male mounting a female during mating.

This was no random coincidence. The fractures weren’t scattered or chaotic; they appeared right where a female’s body would bear the weight of her mate. The conclusion was inescapable: these were injuries sustained during the act of reproduction.

Ruling Out the Wrong Suspects

In science, extraordinary claims require extraordinary evidence. So the researchers meticulously ruled out other possibilities. If the injuries had come from trampling, they would expect to see fractures in a variety of places and in younger dinosaurs too—but the injuries appeared mainly in adults, in the same location, and healed in the same way.

Predation also failed to fit the facts. There were no tooth marks, no signs of tearing or crushing. Likewise, fighting between individuals would have left more chaotic damage, especially to the skull or limbs. Instead, the tail injuries told a quieter, more intimate story—a physical record of mating behavior millions of years old.

The First Evidence of Dinosaur Mating Behavior

For the first time, scientists may have found indirect evidence of sexual behavior in non-avian dinosaurs. These injuries suggest that female hadrosaurs sometimes suffered tail trauma from the weight of their partners during mating. It’s a striking parallel to certain modern reptiles and birds, whose mating rituals can be physically taxing or even dangerous for females.

This discovery opens up a remarkable possibility: that paleontologists could now identify female individuals within species that have long defied such classification. If certain injury patterns are reliably linked to mating behavior, they might serve as a biological signature of gender—one carved into the very bones of prehistory.

The Intimacy of Ancient Giants

There’s something deeply moving about imagining these creatures not as distant monsters, but as living beings with struggles, instincts, and tenderness. For all their size and power, even dinosaurs bore the marks of love and survival. A broken tail spine, healed over time, tells of a moment of connection and risk—a fleeting act that ensured the continuation of life itself.

In that sense, these fossils are not just remnants of anatomy; they are echoes of emotion. They remind us that nature’s drive to reproduce, to carry life forward, is as old as life itself. From hadrosaurs under cretaceous skies to modern animals in our own world, the rhythm of life and love continues unbroken.

From Bones to Behavior

Paleontology has often been compared to detective work, but in reality, it’s more like listening to a whisper across time. Every fossil carries a story, but most are told in fragments. The new research from Dr. Bertozzo’s team shows how advanced technology—combined with careful observation—can bridge the gap between bones and behavior.

By examining how injuries form, heal, and repeat, scientists can reconstruct moments that fossils alone could never reveal. It’s not just about how dinosaurs looked, but how they lived—how they moved, interacted, courted, and cared for one another. It brings us closer to them, not as curiosities of extinction, but as living creatures with instincts and struggles mirroring our own.

The Promise of New Discoveries

If this finding holds true for hadrosaurs, it could revolutionize how paleontologists identify sex in other dinosaur species. Many fossils once thought identical might, upon closer examination, reveal subtle patterns of difference—fractures, wear, or muscle attachments hinting at roles in reproduction or parenting.

For instance, in species where males performed elaborate mating displays or engaged in physical contests for mates, similar signs might appear in their bones. Likewise, females that bore the weight of mounting partners—or even carried eggs—might show distinct skeletal adaptations. Each discovery adds a new chapter to the long-lost story of life on Earth.

The Enduring Mystery of Life’s Drive

What makes this discovery so profound isn’t just its scientific novelty—it’s what it reveals about the continuity of life. Across hundreds of millions of years, from dinosaurs to birds to mammals, the struggle and beauty of reproduction have shaped the evolution of species. The same biological forces that guide courtship dances in cranes or the songs of whales also guided the behavior of creatures long vanished into stone.

It’s humbling to realize that through every era, life has found a way. Even when the evidence is reduced to fractured bones, the story of love and survival still finds a voice.

More information: Filippo Bertozzo et al, Deciphering causes and behaviors: A recurrent pattern of tail injuries in hadrosaurid dinosaurs, iScience (2025). DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2025.113739