Long before the first hoofbeats echoed across the Eurasian steppes or reverberated through the plains of North America, the horse was already in motion—part of a story etched deep into the soil, told in the DNA of fossilized bones, and remembered in the songs and oral traditions of Indigenous Peoples. The horse, contrary to popular myth, did not arrive in the Americas with European settlers. It was born here—on this very continent—nearly four million years ago.

From those ancient beginnings, a remarkable saga unfolded. As glaciers waxed and waned and sea levels rose and fell, horses embarked on vast intercontinental journeys, migrating across the Bering Land Bridge that once connected Alaska and Siberia. Their migration was not a singular event, but a centuries-long, back-and-forth odyssey—one of resilience, adaptation, and survival.

Now, a groundbreaking international study led by 57 researchers, including 18 Indigenous scientists from nations such as the Lakota, Dene’ (Athabascan), Blackfoot, and Iñupiaq, is rewriting the story of the horse with a holistic approach that integrates cutting-edge genomic sequencing and ancient wisdom carried across generations.

Published in Science, the study, titled “Sustainability insights from late Pleistocene climate change and horse migration patterns,” sheds new light on how these majestic creatures shaped, and were shaped by, the environmental transformations of the Late Pleistocene.

More Than a Species: The Sacred Role of the Horse

For many Indigenous Peoples, the horse is far more than a domesticated animal—it is a spiritual and ecological partner, a keystone species within the great web of life. It is a being with its own wisdom and agency, understood through traditional scientific systems that predate modern academia by millennia.

“We understand the Horse Nation to be a keystone species that, together with the other life forms with which it shares relationality, brings balance to the ecosystem,” says Chief Harold Left Heron, a traditional Lakota knowledge keeper.

The horse is interwoven into creation stories, cosmologies, and everyday life. Its behaviors, migratory instincts, and adaptability have long offered lessons about resilience and environmental stewardship. For thousands of years, Indigenous communities have moved with the horse, learned from it, and fought to protect its lineage.

Ancient Roads: The Medicine Man Trail

Among the Dene’ Peoples, oral history speaks of a profound path—the Medicine Man Trail. This vital corridor, now buried beneath oceans and forests, once linked the American and Eurasian continents. Along this trail, not only did horses move freely, but so too did knowledge, cultural exchange, and sacred responsibilities.

“This knowledge is held in our songs, stories and in the sciences and lifeways we carry,” explains Wilson Justin, an Upper Ahtna/Upper Tanana Dene’ Elder. “Singing the song of life ensures that the world is balanced, and life can diversify and continue in a good way.”

The Medicine Man Trail is not merely a memory of the past. It is a metaphor for survival, for interconnectedness, for the path life must follow to flourish. In rediscovering the ancient steps of horses along this trail, we also reclaim a part of our own shared journey.

Digging Through Ice and Time: Genomic Breakthroughs

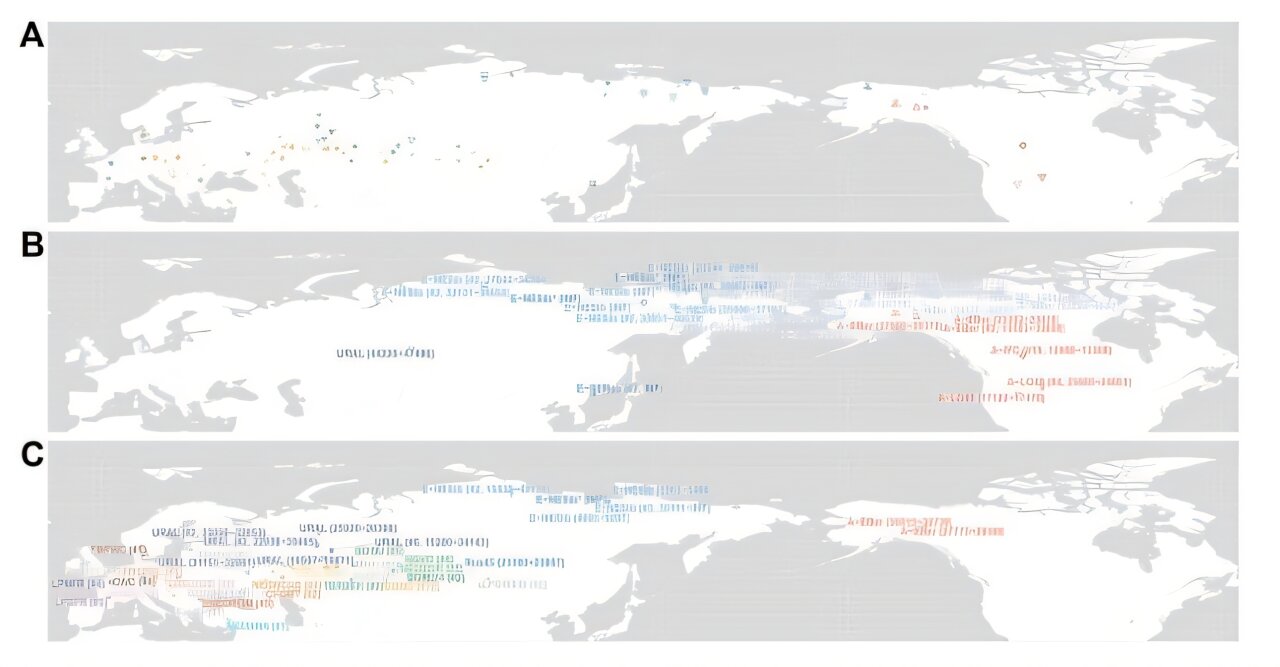

To scientifically map the migration of horses, researchers turned to one of the Earth’s most reliable time capsules: permafrost. The frozen soils of Alaska, the Yukon, and Siberia have preserved horse remains for tens of thousands of years. In these cold environments, DNA survives like a fossil of memory.

“In this study, we harnessed the full power of the latest generation of DNA sequencing instruments, and Lakota scientific genomic principles, to uncover a more complete diversity of horse lineages,” says Dr. Ludovic Orlando, director of the Centre for Anthropobiology and Genomics of Toulouse.

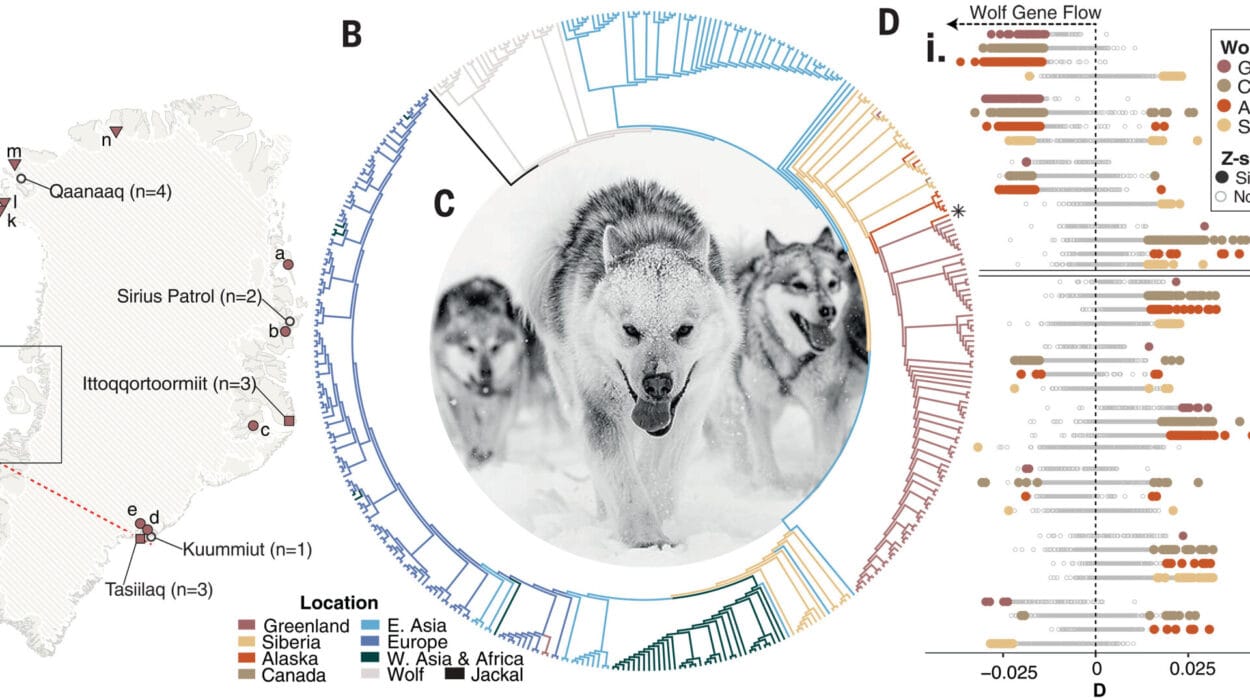

The research sequenced 68 ancient horse genomes, some dating back nearly a million years. The effort was collaborative and respectful: the samples came from both sides of the Pacific, and co-authors represented the regions from which each bone or tooth originated. This respectful approach, which honored both territory and tradition, made the science stronger.

Continents in Conversation: East to West, and Back Again

Perhaps the most surprising finding from the study is just how frequently horses crossed continents—and in both directions.

“We found that North America alone had at least three distinct horse lineages,” says Dr. Yvette Running Horse Collin, a Lakota scientist who led the genomic lab work and ensured that all Indigenous scientific protocols were followed. “One lived south of the massive ice sheets, another across Alaska and the Yukon, and a third, at the westernmost edge of Alaska, had direct genetic links to Eurasia.”

That third lineage traces its roots to horses from the Ural Mountains, in what is now Russia. As sea levels dropped during glacial periods, a land bridge emerged—Beringia—connecting Siberia and Alaska. Horses used this corridor multiple times, moving eastward into the Americas between 50,000 and 19,000 years ago.

Even more remarkably, horses also migrated in the opposite direction during earlier climate phases. Following the Pacific coastline, they moved from the Americas back into Asia, reaching as far as northeastern China. Their genetic traces later appeared as far west as Anatolia and the Iberian Peninsula.

These revelations challenge long-held assumptions about migration, extinction, and domestication. They show that horses were global travelers long before humans ever rode them.

When Ecosystems Shifted—and Horses With Them

But movement is not just a story of exploration—it’s a response to necessity. Horses, like all life, followed the changing climate. When ice sheets receded around 15,000 years ago, the Ice-Free Corridor between Alaska and the continental United States opened. Horses living in the Yukon navigated through this changing landscape as grasslands gave way to wetlands.

“These horses lived within a transforming environment,” says Dr. Clément Bataille of the University of Ottawa. His team analyzed carbon and nitrogen isotopes in horse remains to determine what these animals ate and what kind of ecosystems they occupied.

The data revealed that as wetter ecosystems replaced the dry steppe-tundra, horse populations declined. The lush meadows that had once supported large herds disappeared. Megafauna like horses could no longer thrive in the same numbers, and many lineages went extinct.

Sacred Science: Applying Ancient Knowledge to a Modern Crisis

For Indigenous scientists like Jane Stelkia, an Elder of the sqilxʷ (suknaqin/Okanagan Nation), these migrations and extinctions carry deep lessons for today.

“In this study, Snklc’askaxa—the Horse Nation—is offering us medicine by reminding us of the path all life takes together to survive and thrive,” she explains. “It is time that we come together, again, to help life find the openings and points to cross and move safely.”

Stelkia and others emphasize that the study is not just about the past—it’s a mirror for the present. In a world rapidly destabilized by climate change, the old trails of migration offer blueprints for survival. Ecological corridors, like the ancient Medicine Man Trail, must be preserved and restored.

Yutaŋ’kil: The Movement That Sustains Life

The Lakota concept of yutaŋ’kil—that life never moves alone, but follows its ecosystem—is at the heart of this work. It’s a philosophy of interdependence. Horses didn’t migrate in isolation; they moved with grasses, predators, and people. Their story is part of a larger biological and spiritual ecosystem.

“We are implementing the findings of this paper in He’Sapa, our sacred Black Hills,” says Chief Joe American Horse. The Black Hills Wild Horse Sanctuary is now a living laboratory for restoring both horses and habitat, guided by traditional knowledge and modern science alike.

Collaboration as a Compass

The success of this study reflects a broader shift in how science can and should be done. Indigenous knowledge was not a supplementary component—it was foundational. From methodology to authorship, the project centered reciprocity, respect, and representation.

The University of Ottawa played a vital role, providing world-class isotope geochemistry labs and infrastructure. But it was the partnership with Indigenous communities—especially in the Arctic—that gave the research its depth and authenticity.

“This work is an example of how interdisciplinary collaboration can help us understand past climate-driven ecological changes,” says Dr. Bataille. “And it aligns with our commitment to Indigenous partnerships and Arctic-focused research.”

A Future Informed by the Past

In the horse, we find a living metaphor for resilience, adaptation, and the deep wisdom of movement. Its journey is not over. The lessons of its ancient crossings offer hope for a world once again on the brink of ecological transformation.

As glaciers melt, species migrate, and old certainties collapse, it may be the remembered paths—the Medicine Man Trails of both spirit and science—that light the way forward.

Reference: Yvette Running Horse Collin et al, Sustainability insights from Late Pleistocene climate change and horse migration patterns, Science (2025). DOI: 10.1126/science.adr2355