Tens of thousands of years ago, long before modern cities rose from the earth, a completely different Taiwan existed—a land not of misty forests and mountains, but of open grasslands, meandering rivers, and vast herds of colossal creatures. This was Taiwan during the Pleistocene epoch, a period that now feels as distant as myth. Yet, through the lens of science, this vanished world is reawakening.

A groundbreaking study by researchers from the National Museum of Natural Science (NMNS) and National Taiwan University (NTU) has brought this lost chapter of Earth’s history vividly back to life. For the first time, scientists have unveiled the ecological portrait of ancient Taiwan—a warm, arid savanna teeming with life, stretching across what is now the Taiwan Strait. The findings, published in Royal Society Open Science, paint a picture that redefines how we understand Taiwan’s prehistoric environment and the creatures that once roamed it.

The Clues Hidden in Elephant Teeth

At the heart of this discovery lies an unlikely storyteller: the Straight-tusked Elephant, known scientifically as Palaeoloxodon. Though extinct, these giants have left behind enduring fossils—especially their teeth, which have proven to be nature’s time capsules. Within their enamel, traces of ancient elements remain locked away, preserving chemical signatures that reveal what the elephants ate, drank, and even how they lived.

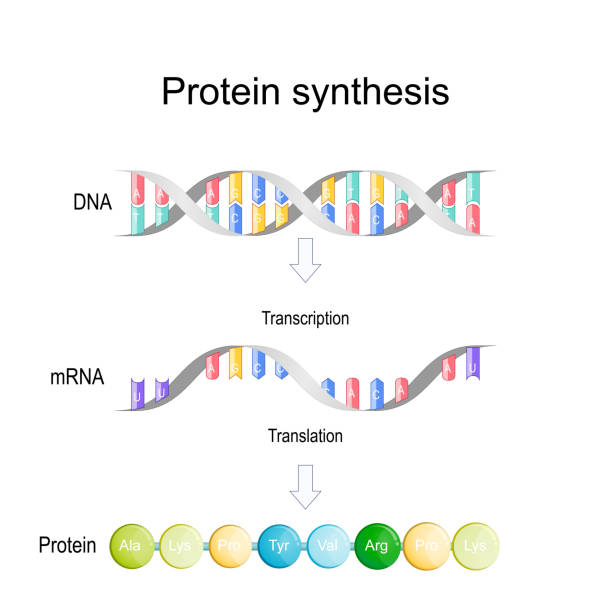

Dr. Chun-Hsiang Chang, a paleontologist at NMNS, led the isotope analysis of Palaeoloxodon tooth enamel and found something extraordinary. The chemical patterns showed that these elephants fed almost entirely on C4 plants—a group of grasses and herbs that thrive in hot, dry climates. This was a startling contrast to their relatives in Europe and Japan, whose diets centered around C3 plants, typically found in cooler, forested regions.

This dietary distinction was not just a matter of preference; it reflected a profound environmental difference. The Taiwanese elephants lived not in dense woodlands, but in open savannas similar to those of India or Africa—sunlit expanses of grass and riverbanks where herds grazed beneath wide skies. Taiwan, it seems, was once a land of golden plains and flowing rivers, a far cry from the forested island we know today.

A Bridge Between Continents

During the Pleistocene epoch—spanning roughly 2.6 million to 11,700 years ago—global sea levels were much lower than they are today. The Taiwan Strait, now a body of water separating Taiwan from mainland China, was then an exposed land bridge connecting the island to the Asian continent.

This ancient corridor allowed animals and even early humans to migrate freely across East Asia. Herds of Palaeoloxodon likely roamed alongside other large mammals, such as prehistoric deer and ancient rhinoceroses, all drawn to the fertile grasslands and freshwater rivers that laced the region.

Dr. Chang explains that the dietary differences observed across Palaeoloxodon populations—from Europe to East Asia—highlight a powerful ecological pattern: as latitude changes, so too do climate, vegetation, and ultimately, the way animals live. The Taiwanese elephants, adapted to tropical and subtropical savannas, stand as a testament to this grand evolutionary rhythm—a reminder that even the mightiest species bend to the will of their environment.

Rivers Through Time

While diet reveals much about land, oxygen isotope analysis tells another side of the story: water. Professor Cheng-Hsiu Tsai of NTU, a leading expert on fossil mammals, examined the oxygen isotopes embedded within the same elephant enamel. These isotopes trace the sources of water the animals drank, offering clues about the climate and hydrology of ancient landscapes.

The results were just as remarkable as the carbon findings. The isotopic fingerprints indicated that these prehistoric elephants relied on freshwater rivers, not stagnant ponds or salty estuaries. This confirms the presence of large, flowing river systems cutting through the Pleistocene Taiwan Strait—evidence that this now-submerged region was once a fertile network of rivers and valleys, supporting abundant life.

These rivers were not small streams but majestic, life-giving arteries that nourished a vast savanna ecosystem. They carved through the landscape, shaping migration routes and sustaining the megafauna that depended on them. This revelation not only deepens our understanding of East Asian paleogeography but also provides the first concrete evidence of Taiwan’s ancient river systems before rising seas swallowed them whole.

The Life of a Giant

Fossils do more than describe environments—they can whisper the intimate details of life itself. Through the meticulous work of Deep S. Biswas, a Ph.D. candidate at NTU, sequential isotope analysis along the growth lines of Palaeoloxodon teeth has revealed something profoundly human: the nurturing behavior of mothers toward their young.

The data suggest that juvenile elephants continued weaning until around five to six years of age, similar to modern elephants. This extended period of parental care underscores the intelligence and social complexity of these ancient giants. They lived in structured herds, much like today’s elephants, bound by family ties and emotional bonds that spanned years.

This discovery breathes life into fossils. Suddenly, the ancient savanna is not just a backdrop of dry grass and wind, but a living stage where mothers guided their young through the shifting rivers and tall grasses of a world long vanished beneath the sea.

A Window Into East Asia’s Ancient Ecology

The implications of this study reach far beyond Taiwan. It provides a crucial missing piece in the puzzle of East Asian paleoecology, revealing how regional ecosystems varied across continents during the Pleistocene. The Palaeoloxodon of Taiwan did not merely survive in isolation—they represented a distinct ecological adaptation shaped by tropical conditions, unique even among their species.

This research also challenges long-held assumptions about how the environment of East Asia evolved over millennia. By reconstructing this ancient savanna, scientists can now trace how climatic shifts, vegetation patterns, and animal behaviors interacted to create the diverse habitats that later gave rise to modern East Asia’s landscapes.

Echoes Beneath the Waves

Today, the Taiwan Strait is a stretch of restless ocean between islands and mainland, concealing the memory of its golden past beneath dark waters. Yet, through the dedication of scientists, that memory is rising again—piece by piece, tooth by tooth, isotope by isotope.

The image that emerges is one of resilience and transformation. Where rivers once meandered, tides now surge. Where elephants once walked, ships now sail. The world has changed beyond recognition, but the traces of its former life endure—etched into the chemistry of fossils and the curiosity of those who study them.

More information: Deep Shubhra Biswas et al, A glimpse into a vanished ecosystem: reconstructing diet and palaeoenvironment of Palaeoloxodon from the Pleistocene of Taiwan, Royal Society Open Science (2025). DOI: 10.1098/rsos.250935