Every person alive today is the product of a long, winding, and astonishing evolutionary journey—one that stretches back not just centuries or millennia, but millions upon millions of years. We often take for granted the fact that we walk upright, that we speak in complex languages, or that we can contemplate our own existence. But none of these traits appeared overnight. Each is the result of tiny changes, accumulated slowly over vast stretches of time. The story of human evolution is not just a tale of biology—it is the story of survival, curiosity, adaptability, and transformation.

From the depths of ancient oceans to the treetops of tropical forests, from firelit caves to cities that touch the sky, the human lineage has traveled through eras of unimaginable change. Along the way, it split, branched, and sometimes vanished. Many of our close evolutionary cousins—like Neanderthals and Denisovans—shared this planet with us and then disappeared, leaving only traces in our genes and artifacts in the earth. We, Homo sapiens, are the lone survivors of a diverse and sprawling family tree.

But how did we get here? How did tiny, tree-dwelling primates evolve into beings capable of decoding the structure of DNA, painting masterpieces, sending spacecraft beyond the solar system, and asking where it all began?

To answer those questions, we must look not just at a sequence of bones and fossils but at the unfolding of deep time itself. In this article, we will walk step by step through the incredible timeline of human evolution—from the first simple life forms to the emergence of modern humans. Using scientific discoveries, fossil evidence, and genetic insights, we’ll explore how the past continues to shape who we are, and why understanding our evolutionary roots is essential to understanding ourselves.

This is not merely a history lesson. It is the grand narrative of our existence—written not in ink, but in the ancient language of stone, DNA, and time.

When the Earth Was Young and Life Was Simple (4.5–3.5 Billion Years Ago)

More than 4.5 billion years ago, Earth was born in fire. Its molten surface slowly cooled, giving rise to oceans where the first whispers of life began. For the next billion years, life remained microscopic. Single-celled organisms like bacteria were the only inhabitants of Earth. Among them were cyanobacteria—tiny architects of the atmosphere—which began to produce oxygen through photosynthesis around 2.4 billion years ago, altering the planet’s chemistry forever.

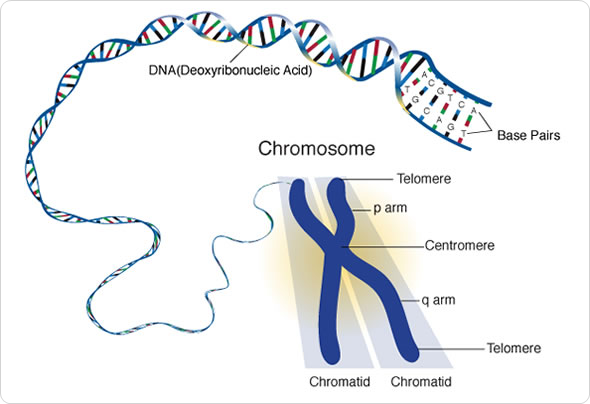

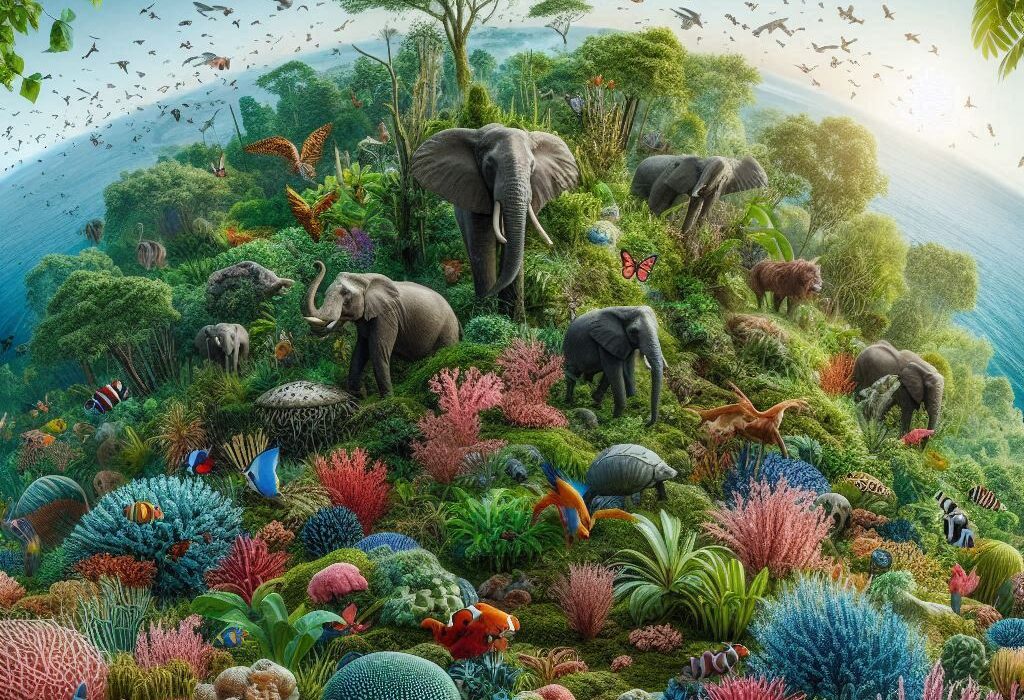

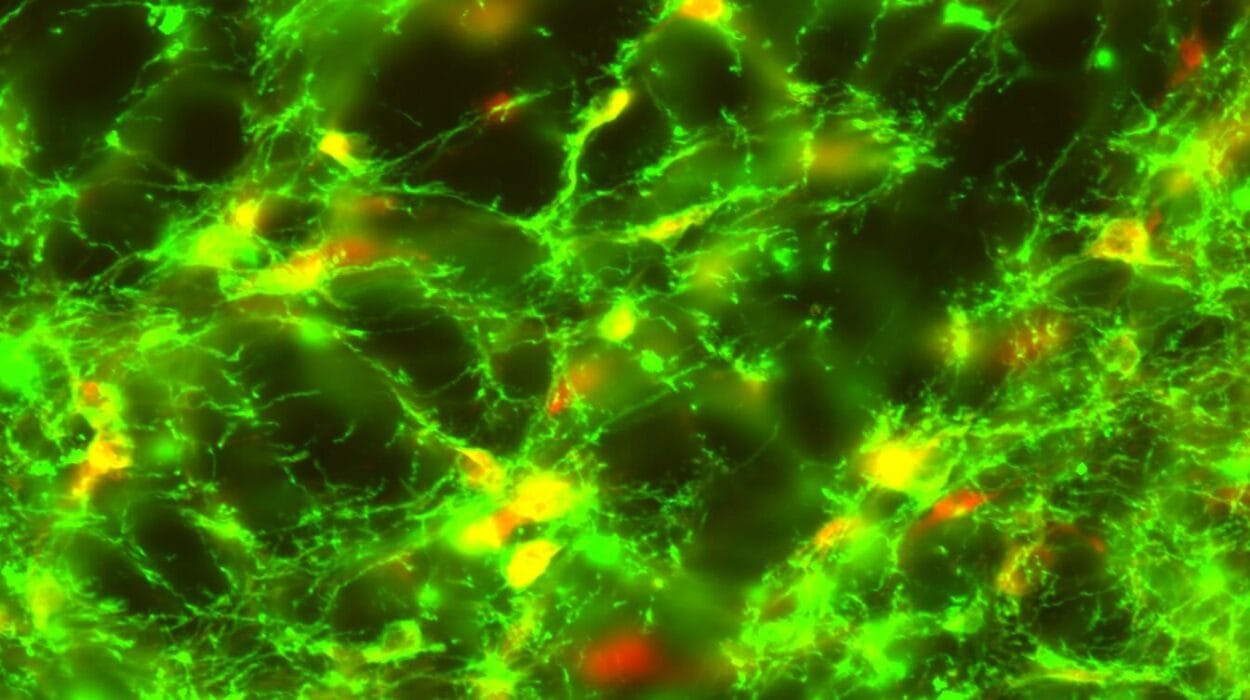

Although these early forms of life were not human or even animal, they set the biological stage for everything to come. Life was evolving, slowly and patiently, through mutation and natural selection. Over unimaginable stretches of time, cells developed complexity. Some learned to live inside others, giving rise to eukaryotes—cells with nuclei. These eukaryotes, emerging around 2 billion years ago, were our very distant ancestors. From them came fungi, plants, animals—and ultimately, us.

The Rise of Animals and the Origins of Vertebrates (600–400 Million Years Ago)

Multicellular life finally exploded into diversity around 541 million years ago during the Cambrian Explosion. Animals began to appear in a dizzying array of shapes, sizes, and functions. Vertebrates—animals with backbones—emerged in the oceans around 525 million years ago. They began as simple fish-like creatures, swimming in shallow seas.

By 360 million years ago, some of these vertebrates had developed lungs and strong limbs, and they crept onto land. These were the tetrapods, and they were the ancestors of all amphibians, reptiles, birds, and mammals. Evolution was crafting ever more elaborate forms of life, and with each generation, nature experimented.

Mammals, including the ancestors of humans, evolved around 200 million years ago during the age of the dinosaurs. They were small, nocturnal, and inconspicuous—survivors rather than dominators. But when the dinosaurs went extinct 66 million years ago in the aftermath of a massive asteroid impact, mammals seized their chance.

From Primates to Apes: The Family Tree Narrows (60–10 Million Years Ago)

Primates evolved roughly 60 million years ago. These small, tree-dwelling mammals had grasping hands, forward-facing eyes, and large brains for their size. These traits, evolved for life in the trees, became foundational in the story of humanity.

By around 30 million years ago, the primates split into two major groups—Old World monkeys and apes. The latter group, the hominoids, included gibbons, orangutans, gorillas, chimpanzees, and eventually, humans. The great apes were highly intelligent and social, and they thrived in the forests of Africa and Asia.

Somewhere between 13 and 10 million years ago, a common ancestor of all the great apes walked the Earth. This creature likely looked much like a modern ape but carried within its genes the seeds of something new: the potential for upright walking, advanced tool use, and the beginnings of culture.

Around 7 to 8 million years ago, one lineage split from the common ancestor shared with chimpanzees. That line would eventually lead to humans. We do not know the name of that first ancestor, but it marked the beginning of an extraordinary journey—one that would reshape the Earth and gaze at the stars.

Sahelanthropus and the First Upright Walkers (7–5 Million Years Ago)

Fossils found in Chad, dating to around 7 million years ago, belong to a species called Sahelanthropus tchadensis. This early hominin had a mix of ape-like and human-like traits. Its brain was small, but the position of its foramen magnum—the hole where the spinal cord connects to the skull—suggests it held its head upright, indicating the possibility of bipedalism.

Around 6 million years ago, in what is now Kenya, a creature called Orrorin tugenensis also walked upright. Then came Ardipithecus ramidus, around 4.4 million years ago. Discovered in Ethiopia, “Ardi” had feet adapted for walking as well as grasping trees. This suggests a transitional lifestyle: partly arboreal, partly terrestrial.

These early hominins were not yet human, but they walked on two legs, which freed their hands. This change would alter everything—from tool use to brain development to the eventual rise of civilization.

The Australopithecines: Walking with Confidence (4–2 Million Years Ago)

By 4 million years ago, a new genus had emerged: Australopithecus. Among the most famous of its species is Australopithecus afarensis, best represented by “Lucy,” a fossilized skeleton discovered in Ethiopia and dated to 3.2 million years ago. Lucy walked upright and had relatively long arms, suggesting she still spent time in trees.

These australopithecines were small-bodied, big-brained compared to earlier primates, and increasingly comfortable on the ground. They likely used simple tools—stones or sticks—for foraging. They lived in groups and perhaps developed rudimentary forms of communication. They were prey as often as predator, but their agility and intelligence helped them survive.

Between 3 and 2 million years ago, several species of Australopithecus roamed eastern and southern Africa. Among them was Australopithecus africanus, thought to be a likely ancestor of the genus Homo. Evolutionary branches grew and died, but one path was leading toward us.

Homo habilis and the Dawn of Human Intelligence (2.4–1.5 Million Years Ago)

Around 2.4 million years ago, the first members of the genus Homo appeared. Homo habilis, or “handy man,” was named for the stone tools found near its fossils. These early humans had larger brains than Australopithecus and were likely more dependent on tools for survival.

They lived in complex social groups and may have scavenged or hunted small animals. Their teeth were smaller, suggesting a shift in diet. The use of tools allowed them to crack open bones for marrow—a rich source of calories that may have fueled further brain growth.

Although they still looked primitive by today’s standards, Homo habilis marked a turning point. The cognitive gap between them and earlier hominins was vast. The line between survival and innovation was beginning to blur.

Homo erectus: The First Global Wanderers (1.9 Million–140,000 Years Ago)

Around 1.9 million years ago, Homo erectus emerged in Africa. This species was larger, stronger, and more advanced than its predecessors. Its brain was about two-thirds the size of a modern human’s, and its body proportions were similar to ours. Homo erectus used more sophisticated stone tools, possibly controlled fire, and built shelters.

But perhaps the most remarkable trait of Homo erectus was its wanderlust. It was the first human species to leave Africa. Fossils have been found in Georgia (1.8 million years ago), Indonesia (1.6 million years ago), and China (1.2 million years ago). Homo erectus adapted to many environments, from tropical forests to dry grasslands.

Fire provided warmth and protection, allowing these early humans to settle in colder climates. Cooking may have made food more digestible, improving nutrition and supporting brain growth. Social bonds deepened. Cooperation became essential. The long human journey had gone global.

Neanderthals, Denisovans, and the Branching Tree of Humanity (800,000–40,000 Years Ago)

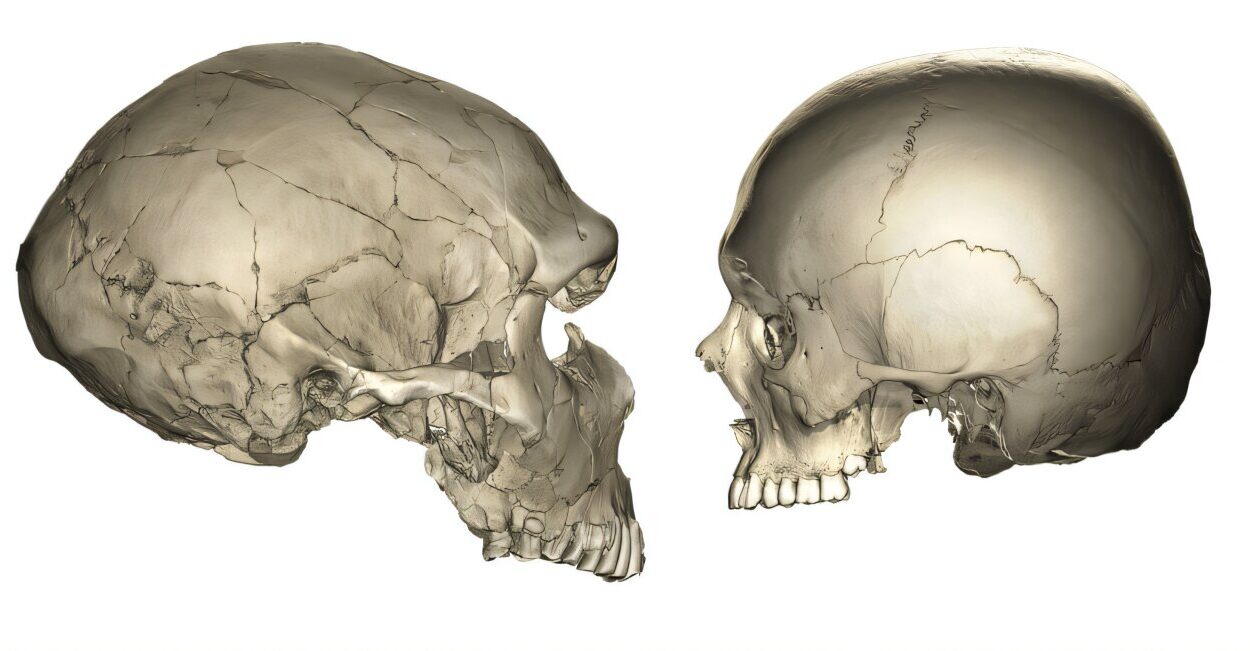

From Homo erectus came a variety of species adapted to different environments. In Europe and western Asia, Homo neanderthalensis—the Neanderthals—evolved around 400,000 years ago. In eastern Asia, another group emerged: the Denisovans, known primarily through genetic evidence and a few fossil fragments.

Neanderthals were not brutish cavemen, as once believed. They had larger brains than modern humans, buried their dead, cared for the injured, and created art and tools. Their lives were hard, marked by cold climates and dangerous hunts, but they were intelligent survivors.

Meanwhile, early Homo sapiens were evolving in Africa. Fossils from Morocco, dated to around 300,000 years ago, show a mix of modern and archaic features. These early humans had high foreheads, smaller faces, and behavior increasingly shaped by culture.

Homo sapiens: The Emergence of Modern Humans (300,000 Years Ago–Present)

Modern humans, Homo sapiens, emerged in Africa roughly 300,000 years ago. They spread slowly at first, moving into the Middle East around 100,000 years ago, and into Europe and Asia by 60,000 years ago. Along the way, they encountered and interbred with Neanderthals and Denisovans, leaving traces of these ancient relatives in our DNA.

What set Homo sapiens apart was not just biology, but behavior. Around 50,000 years ago, a “cognitive revolution” occurred. Humans began to make intricate tools, jewelry, cave paintings, and musical instruments. They developed language, rituals, and myths. Culture became a survival tool as powerful as fire or stone.

As humans spread across the globe, they adapted to new environments, domesticated animals, and transformed landscapes. By 15,000 years ago, they had reached the Americas. By 4,000 years ago, they had colonized remote Pacific islands.

Agriculture, which began around 10,000 years ago in the Fertile Crescent, changed everything. People settled into villages, built cities, and formed civilizations. Writing was invented, and with it, history began.

The Present and the Future: Evolution Continues

Today, all humans belong to one species—Homo sapiens. We differ in language, culture, and appearance, but genetically, we are nearly identical. Our closest living relatives, chimpanzees and bonobos, share 98.8% of our DNA. The differences lie not in raw genes, but in how those genes are expressed.

Human evolution has not stopped. We are still changing—biologically, socially, technologically. Our brains are adapting to digital life. Our bodies respond to modern diets and sedentary lifestyles. Genetic editing, artificial intelligence, and climate change may steer our evolution in new and unpredictable directions.

But even now, deep in our blood, we carry the legacy of ancient wanderers, toolmakers, and fire-keepers. We are the product of billions of years of life’s relentless creativity. From humble single cells to cosmic dreamers, we are nature looking back at itself in wonder.