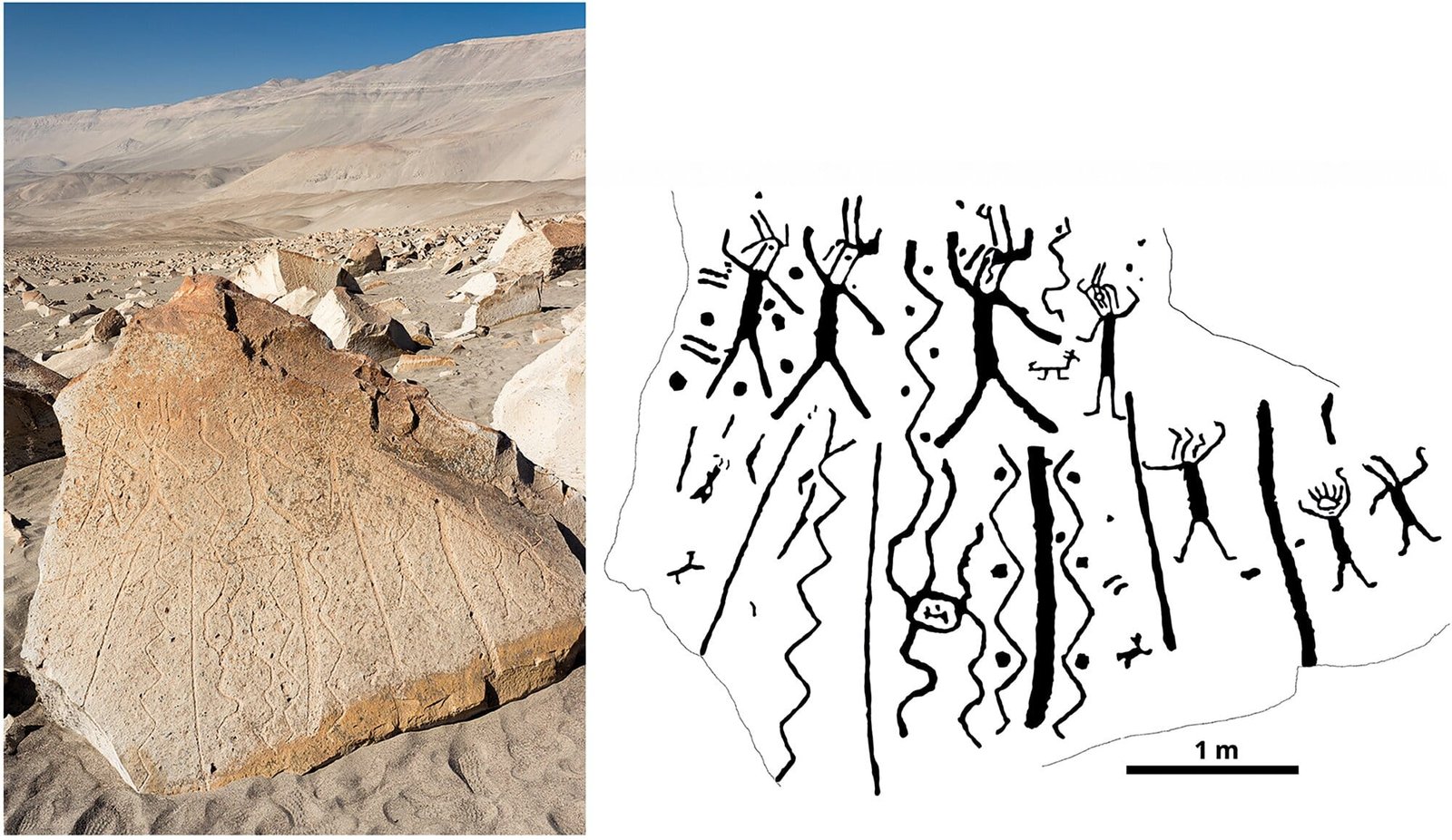

Amid the arid expanse of southern Peru, where the land breathes heat and silence, thousands of boulders lie scattered like the bones of forgotten giants. This place, known as Toro Muerto—“Dead Bull” in Spanish—is not merely a graveyard of stone. It is one of the most enigmatic rock art sites in the Americas, a sprawling ten-square-kilometer canvas in the desert, etched with messages from a distant past.

These stones are alive with human stories. They whisper of bodies in motion, arms raised in exaltation, limbs bent in rhythm, heads tilted to unseen melodies. The human figures—called danzantes by scholars—appear to dance across the rock faces, surrounded by spirals, zig-zags, squiggles, dots, and arcs. Each carving is a still frame of movement, emotion, and energy, as if the rocks themselves were once swaying to an ancient beat.

For decades, Toro Muerto has stood in mystery, admired but rarely deeply studied. Now, a pair of archaeologists from Poland—Andrzej Rozwadowski of Adam Mickiewicz University in Poznań and Janusz Wołoszyn of the University of Warsaw—have looked at the petroglyphs with fresh eyes. Their findings, recently published in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal, offer a bold new interpretation: what if the art was born not merely of ritual, but of altered consciousness? What if the danzantes were dancing not only in celebration—but in hallucination?

Art as Memory of Music and Mind

What Rozwadowski and Wołoszyn found is not merely an assembly of carvings but a choreography of symbols. The danzantes are not alone—they are immersed in what the researchers describe as “energetic” environments. Zig-zag lines burst from their limbs, circles encircle their forms, and squiggly paths swirl around their bodies. It is as though the figures are vibrating. The researchers propose these aren’t random decorations. They may be attempts to visualize the emotional experience of music, and more provocatively, the sensory chaos of a psychedelic state.

Most compelling of all, the Toro Muerto petroglyphs bear striking resemblance to carvings created by the Tukano people of the Colombian Amazon. These carvings, studied more thoroughly in previous research, are closely linked to ayahuasca rituals—ceremonies involving a potent hallucinogenic brew used for spiritual insight, healing, and connection to the unseen world. During these rituals, music, especially repetitive chanting or singing, plays a vital role in guiding the experience.

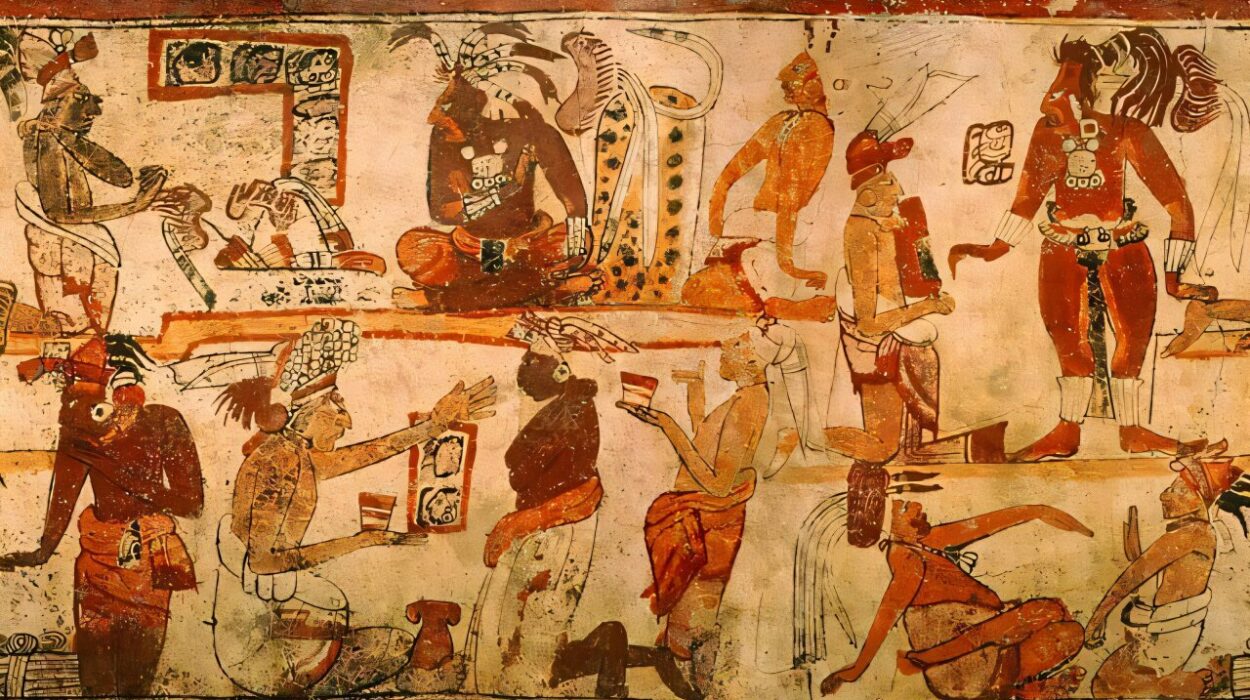

In the case of the Tukano, their carvings attempt to give form to the ineffable. The lines, spirals, and dancing figures are not literal scenes but symbolic echoes of what they felt: movement, music, transformation. The similarity in symbolic language between the Tukano rock art and that at Toro Muerto raises a fascinating possibility—that both peoples, though separated by time and geography, were trying to capture the same universal human experience.

Rozwadowski and Wołoszyn suggest that the carvings in Toro Muerto may have been produced by individuals who were under the influence of a now-unknown hallucinogenic plant, possibly combined with rhythmic singing or chanting. The figures on the rocks were not simply dancers—they were participants in a visionary journey. And the rocks were their memory stones.

The Deliberate Dance of the Artists

These were not wild scratchings made in chaos. One of the most interesting findings from the researchers’ analysis was the remarkable order underlying the carvings. Despite the energetic subjects, the petroglyphs exhibit consistent spacing, composition, and coloration. It appears the artists had a clear intention, a vision they carefully translated into stone.

This contradicts a common assumption that hallucinogen-influenced art must be erratic or impulsive. Instead, these carvings show planning and precision—suggesting that altered states were not an escape from structure, but a gateway into a deeper, more focused creativity. The hallucinations, then, may have acted as tools—not distractions—that opened new ways of seeing and interpreting the world.

The zig-zag lines, for example, are often used in psychedelic cultures to depict energetic movement or the perception of vibration—sensations commonly reported by those under the influence of hallucinogens. The dots and circles may symbolize sound or visual trails. Together, these motifs seem to embody the synesthetic blending of senses that occurs during intense psychedelic experiences—where sound becomes visible, and emotion takes shape.

A Lost Language of Ecstasy

While the exact plant substances used remain unidentified, there is ample evidence that pre-Columbian Andean cultures were familiar with a variety of psychoactive substances. From San Pedro cactus (containing mescaline) to anadenanthera beans (containing DMT-like compounds), ancient peoples of the region had access to powerful tools for altering consciousness. Archaeobotanical evidence has revealed the presence of such plants in ritual sites across Peru, suggesting that hallucinogenic experiences may have been a central feature of religious and artistic life.

The danzantes, then, may not be ordinary human figures. They could represent shamans, ritual leaders, or participants in ecstatic rites—bodies not only moving to rhythm but dissolving into it, becoming intermediaries between worlds. The carvings may not depict a moment in time, but rather a visionary state, a journey of the self, undertaken in sound, in sensation, in surrender.

This raises broader questions: What role did these altered states play in the cultural identity of those who made the carvings? Were the images meant to be permanent guides for future ceremonies? Were they invitations into the sacred? Warnings? Celebrations?

Bridging Worlds: From Dancers to Dreamers

What makes the Toro Muerto petroglyphs so powerful is not only their beauty but their humanity. Across thousands of years and miles, we can still feel the pulse behind them. We see joy in the lifted arms of the dancers, chaos in the swirls that surround them, longing in the etched eyes that stare outward from stone.

These carvings are not just art—they are windows into minds that tried to make sense of experiences that defied ordinary language. In doing so, they remind us that the impulse to capture emotion, rhythm, and spiritual transcendence is not new. It is ancient. It is part of us.

Whether or not the creators of Toro Muerto were singing under the spell of psychedelics, what is certain is that they were communing with something deeper than themselves. They carved to remember. To celebrate. To guide. And perhaps to heal.

The Ongoing Mystery of Toro Muerto

As modern archaeologists return to sites like Toro Muerto, armed with both science and imagination, they are not merely cataloging symbols. They are trying to read a forgotten script of human feeling—one written in the language of vision, music, and myth.

Rozwadowski and Wołoszyn’s research is not the final word on Toro Muerto, but it offers a crucial insight: that art, even when ancient and weathered, still holds the emotional fingerprints of its creators. It shows that ritual, art, music, and mind-altering experience may not be separate domains—but parts of a single human drive: to transcend, to express, and to connect.

In the end, the figures dancing across the desert stone are not so different from us. They too were seeking beauty in chaos, meaning in rhythm, and voice in the silence.

They too, perhaps, were simply trying to remember how it felt to sing while the stars spun and the earth turned beneath their feet.

Reference: Andrzej Rozwadowski et al, Dances with Zigzags in Toro Muerto, Peru: Geometric Petroglyphs as (Possible) Embodiments of Songs, Cambridge Archaeological Journal (2024). DOI: 10.1017/S0959774324000064