Beneath a crumbling limestone overhang in the steep valleys of northwestern Italy, the past has left its whispers. A broken flint blade here, a blackened shell there. Ashes long cold. For tens of thousands of years, these fragments lay untouched, buried beneath windblown dust and the weight of time, waiting for someone to listen.

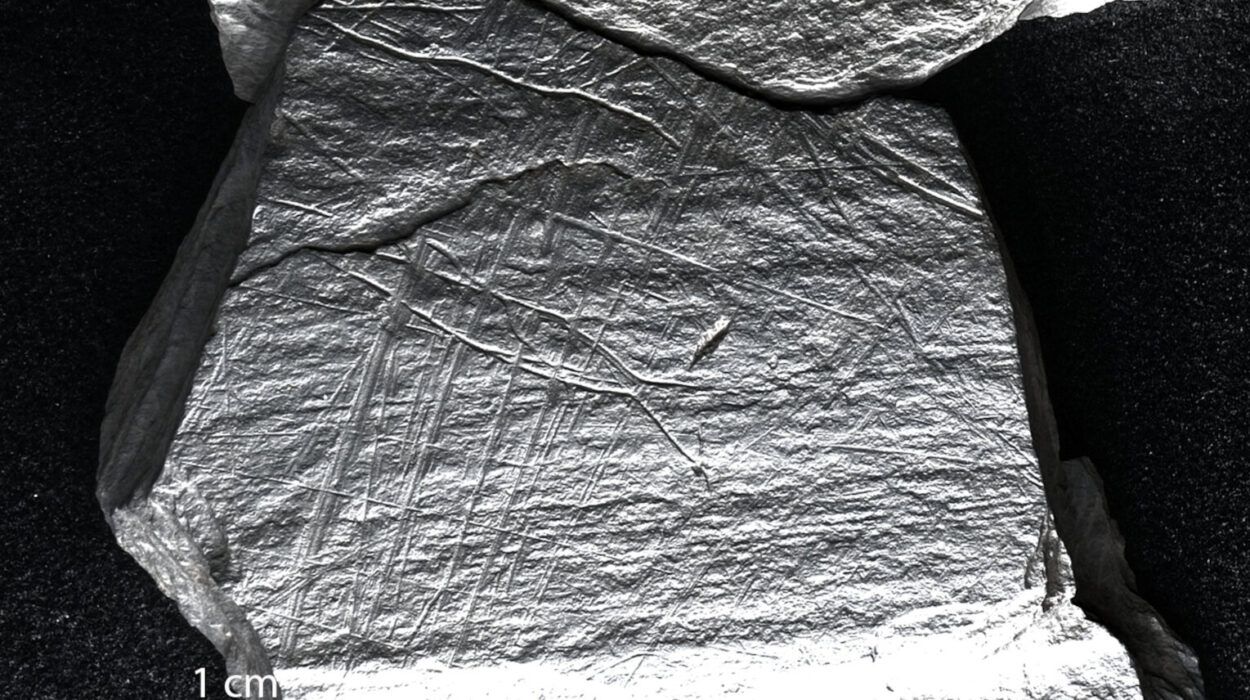

At Riparo Bombrini, a rock shelter nestled against the jagged Ligurian cliffs, archaeologists have finally done just that. In a study published in the Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory, a team of scientists from Université de Montréal and the University of Genoa has pieced together a story that challenges one of our most persistent myths: the belief that Neanderthals, our extinct cousins, were crude, unthinking creatures—shuffling through life in the shadows of our own greatness.

What the research reveals is something very different, and far more moving. Neanderthals, it turns out, were not so different from us. They were architects of their own small worlds. They planned. They remembered. They made themselves at home.

A Shared Architecture of Living

When modern archaeologists look at ancient sites, they don’t just dig for objects—they dig for patterns. Where things are found often tells us as much as what is found. At Riparo Bombrini, layers of human occupation—stacked like pages in a very slow-moving book—contain traces of two kinds of people: Neanderthals from the Mousterian period, and Homo sapiens from the Protoaurignacian.

The researchers, led by UdeM doctoral student Amélie Vallerand, mapped how stone tools, animal bones, ochre, and even sea shells were distributed across the shelter’s surface. By charting these artifacts with precise spatial and statistical tools, they created a kind of heatmap of ancient behavior. Each cluster of tools or bones pointed to something: a place where someone sharpened a blade, butchered a carcass, adorned themselves, or tossed scraps onto a refuse heap.

What emerged was a striking realization. Both Neanderthals and Homo sapiens had used the space in remarkably similar ways. They had divided the shelter into zones of high and low activity. They had central hearths and consistent trash areas. There was rhythm to their movement, intention to their arrangement. There was memory, too—evidenced by the recurring placement of hearths across multiple occupations.

This wasn’t randomness. It was design. It was culture.

The Mark of the Familiar

One of the most powerful insights from the Riparo Bombrini site is that both groups returned again and again. Their reoccupation of the same zones, the preservation of layout, suggests not only continuity but a kind of mental mapping. These were not aimless wanderers. They knew this place. They remembered its corners and contours. They honored its usefulness by maintaining its order.

For archaeologists, these clues are as valuable as any carved artifact or painted wall. They speak to the way ancient humans—regardless of species—thought about their environment. The hearth was not just where you cooked. It was the glowing heart of the home. Around it, life happened: stories were told, tools were shaped, wounds were treated, food was shared.

That the Neanderthals did this too tells us something profound. It tells us they weren’t just surviving—they were living.

Different Paths Through the Same Shelter

Yet while the basic architecture of living was shared, differences also emerged. The Neanderthal levels showed lighter use, with fewer artifacts and less intense activity in each zone. This suggests a more mobile lifestyle. Neanderthals, facing the challenges of a rapidly changing climate, may have moved frequently across landscapes, using the shelter briefly before continuing on. Their visits were precise and purposeful—perhaps a stop along a larger journey.

In contrast, the Homo sapiens levels revealed both short- and long-term occupations, with denser artifact clusters. This dual strategy suggests that early modern humans were adapting differently, mixing mobility with stability, and establishing more complex logistical systems as they explored and claimed new territory.

Still, in both cases, the same space was divided and shaped with logic. Both groups organized their activities. Both adapted to the land’s offerings. And both, importantly, left behind patterns of use that reflected not just reaction to the environment, but planning, memory, and cultural knowledge.

A Conversation Without Words

There is something haunting in the idea that these two human species—so similar and yet never meeting—occupied the same shelter, just separated by time. The transition from Neanderthal to Homo sapiens use at Riparo Bombrini happened swiftly, archaeologically speaking. The Late Mousterian layers give way to the Protoaurignacian with no signs of contact.

And yet, through the echoes of spatial organization, the two species seem to speak to one another. Not with words, but with habits. With ways of making a place livable. With the arrangement of stones and bones and ash. Their conversation is etched in the soil.

Archaeologist Julien Riel-Salvatore, a co-author of the study, has spent years challenging outdated ideas about Neanderthal inferiority. This research adds weight to a growing body of evidence that Neanderthals were capable of symbolic thought, planning, and culture. They weren’t brutish. They were familiar.

As Vallerand put it, “Like Homo sapiens, Neanderthals organized their living space in a structured way, according to the different tasks that took place there and to their needs.” Her statement is more than scientific—it is almost poetic. It suggests a common humanity that stretches across the great divide of extinction.

The Living Room of the Ancients

When we think of intelligence, we often focus on the spectacular: the towering monuments, the painted caves, the dazzling tools. But intelligence also lives in the quiet acts: knowing where to put the fire so the smoke rises just right; storing tools where children won’t trip over them; setting up a refuse pit far enough to keep the smell away but close enough for convenience.

At Riparo Bombrini, the hearthstones tell us that intelligence was not just a trait of Homo sapiens. It belonged to Neanderthals too. They had their own kind of grace, their own domestic elegance.

The shells found at the site—carried up from the nearby Ligurian coast—may have been decorative, or held symbolic meaning. The ochre hints at body painting or ritual. These are not the behaviors of simple creatures. They are the traces of minds at work—minds that felt, remembered, organized, and perhaps even dreamed.

A Legacy in the Dust

In the end, what makes Riparo Bombrini so extraordinary is not just the evidence it preserves, but the humanity it restores. It bridges the space between two species—between the known and the forgotten—and reminds us that home is not a modern invention. It is ancient. It is sacred.

We now know that the Neanderthals who knelt by the fire at Riparo Bombrini, who cracked bones for marrow and stacked shells in the corners, were not waiting to be replaced. They were living with intention, as we do now. The difference is only time.

Their lives—traced in clusters of stone and char—invite us to rethink what it means to be human. To be organized, to be mindful of space, to value comfort and familiarity. These are not luxuries. They are the essence of how our species—and those close to us—have always carved meaning from the world.

So the next time you rearrange your living room, or light a fire, or clean your kitchen, think of them. Think of the Neanderthal who shaped their shelter with the same quiet logic. And remember: they were not so different.

They, too, made themselves at home.

Reference: Amélie Vallerand et al, Homo sapiens and Neanderthal Use of Space at Riparo Bombrini (Liguria, Italy), Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory (2024). DOI: 10.1007/s10816-024-09640-1